As with so many features of the long history of Ipswich (and elsewhere), it is sometimes difficult to untangle changes over time. One question people ask is: what was the route of the rampart around the ancient town centre? Also, where were the gates in the defences allowing access to Ipswich?

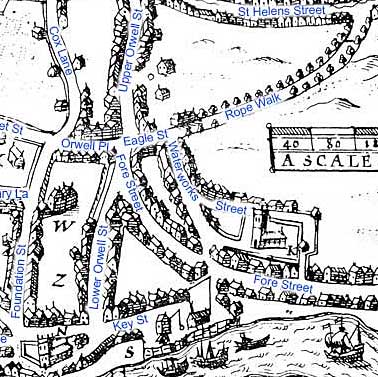

Speed's map of 1610

John Speed's map, described and filleted on this website, shows hatching around the northern perimeter of the old town, but what happens to the east and west?

October 2021: John Norman has had sight of a collection of cuttings which belonged to Edward Grimwade (1812-1886): clothier, Congregationalist and thrice mayor of Ipswich. Amongst the papers he received was a book, a very limited edition The Memorials of Edward Grimwade which is a reprint of the obituaries that appeared, following his death/funeral/memorial services in local newspapers and national journals (e.g. The Christian World). The East Anglian Daily Times (EADT) article fills 21 pages of the 140 page book. (Grimwade Memorial Hall in Fore Hamlet was erected in his memory).

A cutting from the local press (probably the EADT) from Griwade's collection has great interest to the matter in hand. The transcription here follows all the original punctuation (lots of commas), but reformats the article and adds headings for ease of digestion. Because of the mention of 'making a trench a few days since for sanitary purposes', we can date the article to the digging of the Victorian sewers in in Ipswich (1881-2) which were designed by engineer Peter Schuyler Bruff, who contibuted so much to the town where he made his home in Handford Lodge – notably the extension of the railway from Stoke and the building of Stoke Hill tunnel.

'ANCIENT IPSWICH AND THE OLD TOWN WALL.

Traces of the old North Gate?

As some workmen were making a trench a few days since for sanitary purposes in the open space at the top of Northgate Street, they came upon an old foundation of concrete,which may be that of the old North Gate, or that of the old wall, which, prior to the tenth century, surrounded the town, which at that very early period could not have been very extensive.

The route of the

rampart and the gates into the town

It then went down Lady Lane, Tanner’s Lane, and slightly bending, went down Friars’ Road, between the Monastery of Grey Friars and St Nicholas’ Church to the river. From the North Gate easterly it went down Old Foundry Road, Upper Orwell and Lower Orwell Streets. Upon this last route were evidently two other Gates, East Gate and South Gate.

There is little doubt but that the town was strongly fortified by a wall, a fosse or ditch, and earthen rampart, or Vallum. These strong defences, though, could not stand against the Danes, who pillaged the town twice in ten years, from 990 to 1000, but in the reign of King John the fortifications were repaired.

The Letes in the town

• The Gates of the town gave names to the Letes or Wards, such as the following:–

• The East Gate Lete, reached from North Gate, by Archdeacon’s House to the stone cross in Brook Street, called St Lewis’s cross, so down Tankard Street to Friars’ Preachers’ Wall, with Carr Street, St. Margaret’s Green (then called Thingstead), and the lane leading to Little Bolton, and Caldwell or St. Helen’s Street;

• West Gate Lete from North Gate, by Archdeacon’s House to the corner leading to Brook Street and the fish market, and so on to the Cornhill and to West Gate;

• South Gate Lete, from West Gate to St Mildred’s Church, and then to Woulforin’s Lane, in St Peter’s;

• North Gate lete contained all the other parts of the town, with the suburbs beyond Stoke Bridge and St. Clement’s Street.

Archaeological finds

From recent excavations made for building purposes in the town objects of considerable interest and antiquity have turned up. When the new bank was in progress on the Cornhill, at a considerable depth were discovered two Roman vessels, thus placing the history of the town upon the same date as the villa at Whitton.

One is a Gutturnium or water-jug or ewer, employed especially for pouring water over the hands before and after meals. It appears that after it got into disuse as an ewer it served the purpose of a cinerary urn, as it bears blackened marks from the fires of the Pyra, or Rogus, when the calcined bones were further cremated.

The other vessel is of great rarity and interest. It is an adult Tetina, or feeding bottle. It much resembles the Ampula, as it is finished with a tubular spout at the side. This, unfortunately, much mutilated. Many other fragments were also discovered, and with the a patina, or patera, composed of Salopian paste and standing on small feet.

H. WATLING

Derby Villas, Pearce Road.'

Of course, historical and archeological researches since 1882 will have refined our picture of the town's defences, but the reference to the western arm of the rampart reaching down to the river was new information to us. We had always assumed that the extensive and almost impassable marshes to the south-west of the Middle Saxon town were defence enough against invaders, with the river providing a natural defence to the south.

The first defensive ditch-and-bank

Robert Malster in A History of Ipswich (see Reading List) tells us:-

'It was during the Danish occupation that the first town defences were formed. The digging of a roughly circular ditch and bank around the town led to a distortion of the original street layout; for one thing, the ditch cut across the original line of Fore Street [see map] which had led straight into the town before being

diverted to join the

present line of Lower/Upper Orwell Street, presumably entering the town

via the East Gate. Beginning at the edge of the marsh on the western

side of the settlement, the ditch and bank ran around almost the whole

of the populated area, finishing close to the river on the east side,

with the river and marsh providing a defence to the south and the

south-west.

diverted to join the

present line of Lower/Upper Orwell Street, presumably entering the town

via the East Gate. Beginning at the edge of the marsh on the western

side of the settlement, the ditch and bank ran around almost the whole

of the populated area, finishing close to the river on the east side,

with the river and marsh providing a defence to the south and the

south-west.'These defences were presumably set up in response to the advance of the army of Wessex early in the 10th century, but it is believed that they were never used for defensive purposes; the East Anglian Danes capitulated in 918 after Edward the Elder had occupied Colchester. What is perhaps surprising in view of the troubled times in which the Wuffinga dynasty ruled is that Gipeswic apparently had no earlier defences.

'The sequence of defences is obscure, but it is known that the ditch was at one stage filled in and that it was then redug some time in the 11th century. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle tells us that in 991 the Vikings (which is just another way of describing the Danes) 'harried' Ipswich before marching south to win the epic battle of Maldon in which Byrhmoth and his Essex thegns were killed. Then in 1010 a Viking army under Thurkill the Tall sailed up the Orwell and landed at Ipswich, from where they marched west to the great battle at Ringmere, between Bury St Edmunds and Thetford.

'Did the marauding armies put the residents of Gipswic to the sword? Did they burn the town after plundering the storehouses and workshops? We simply do not know; it is uncertain what the writer of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle meant when he wrote of the town being 'harried'. Archaeologists have found burnt buildings, and they have found bodies apparently hurriedly buried close to domestic buildings, but there is no evidence to show that the conflagration was the result of accidental overturning of a candle or of torching by invaders, and little is known about those bodies. ...

[1203]

'Three years after obtaining the charter the town reconstructed the town rampart and ditch on the line of the Danish-period ditch, and in 1299 a grant of murage was obtained from the Crown entitling the town authorities to raise money for the repair of the defences. So it was that in 1302 it is recorded that a "parcell of the Town Ditches [was] granted to Robert Joyliffe, at the yearly rent of sixpence forever; unless it comes to pass that the town shall be enclosed by a stone wall". In 1352 a licence was indeed obtained to strengthen the town with a stone wall, but while excavation evidence suggests a foundation trench might have been dug for this wall it was never built, though town gates were erected at points where important roads entered the circuit of the ramparts, the last of them surviving until the 18th century. It is true that there are references in the town archives to "walls", but an order of 1604 makes it clear that the word is being used to describe the earthen bank and not a stone wall.'

The map detail from Speed, 1610 shows the modern street names in blue. This detail clearly shows how Fore Street, approaching the early 'town centre' (i.e. the area round the northern quays) from the east, bends sharply through ninety degrees to go north to meet Lower/Upper Orwell Streets to avoid the rampart and ditch down Lower Orwell Street, which must have reached down to the river.

Stephen Alsford's excellent 'History of medieval Ipswich' website (see Links):-

'Line of the ditch/wall

The line (which I have indicated by a brown overlay on Speed's map***) was clearly suggested in the topography of the streets into the 19th century (although less so with late 20th-century redevelopment), including street names like Tower Ditches and St. Margaret Ditches. According to a note in one of the Ipswich Domesday Books, the ditches were dug in 1203; but this does not rule out the effort simply being an enlargement or extension of an earlier line of defence. There are fairly frequent references to grants of parcels of the town ditch, particular along the northern boundary, where they are sometimes referred to as the "great ditches of the town". Walls are far less commonly mentioned and their extent is uncertain. In 1302 a burgess was granted a lease of part of the ditches, for 6d. a year, to be voided if the town were ever enclosed by a wall. We hear of town wall in St. Margaret's parish in a grant of 1315, and in St. Mary Elms parish in 1323. A change had occurred between the compilation of a custumal in 1291 and its translation into English in the fifteenth century, since the former refers to a watercourse called "Botflood" (the flooded town ditch?) passing along the side of a road, while the latter refers to it running alongside the wall. What wall-building there was may have focused on areas where the ditches were weakest and may never have proceeded to creation of a continuous line; the eastern and western sides of the borough clearly had walls, but it is less certain that the northern perimeter did.'

[*** Alsford's brown line indicating the rampart starts at the southern end of Lower Orwell Street – not reaching the river dock – runs northwards into Upper Orwell Street across Majors Corner and a small portion of St Helens Street. From there it continues onto St Margarets Street and Crown Street, across St Matthews Street/Westgate Street into Lady Lane. The last coloured section is Tanners Lane (now under Civic Drive) and finishes where it, Friars Street and Greyfriars Road meet. It does not continue further to the river.]

Related pages which refer to the rampart and town gates

Friars Bridge Road;

Egerton's;

North Gate;

Water in Ipswich (under 'The rivers Gipping & Orwell');

©2004 Copyright throughout the Ipswich Historic Lettering site: Borin Van Loon

No reproduction of text or images without express written permission