Water

in Ipswich

Rivers, springs (a

spa town?),

marshes, sewers, bathing places, floods, riverside sculptures

Scientists aver that water on our planet probably came from one

or more 'dirty snowball' comets colliding with the cooling sphere (more

accurately, an oblate spheroid),

creating the potential for life on Earth. Furthermore, today there is

not a drop more and not a drop less of water than there was initially

trapped by our atmosphere.

The streets of old Ipswich were paved not with gold but, very often,

with water. The bowl-shaped terrain of Ipswich centres on the familiar

natural dock with its clearly defined, sharp left-hand turn in the

River Orwell (at Neptune Quay) as it narrows and flows to meet the

non-tidal Gipping. So, at once we have a wide, tidal estuary stretching

up to a large, open pool – sheltered from coastal storms – then

narrowing westwards to the River Gipping which continues into the heart

of the

county. This natural feature is the main reason for the establishment

of the nucleus of the Anglo-Saxon town at this point; more specifically

it is the

narrowing and shallowing of the waterway around the end of today's

Great Whip Street which made the river

fordable. A crossing point on a

water highway, allied to a natural dock is an excellent place to

establish the nucleus of a town. So it was with the Anglo-Saxons and

Gippeswyk, their first town.

Another natural feature which attracted them is the presence of so many

springs in the

surrounding hills of the 'bowl'. The water percolates to the surface

through green sand and gravel layers, purifying it. The clean spring

water is held in the permeable Red Crag above, but cannot penetrate the

alluvial clay present in areas of Ipswich, so it

flows downhill on the surface. This is particularly so of the springs

around Cauldwell ('cold well/cold stream') Hall and those found in and

around

Christchurch and Holywells ('hollow wells' hence the name)

Parks. See our Street name derivations

page for these and many other sources.

The rivers Gipping & Orwell

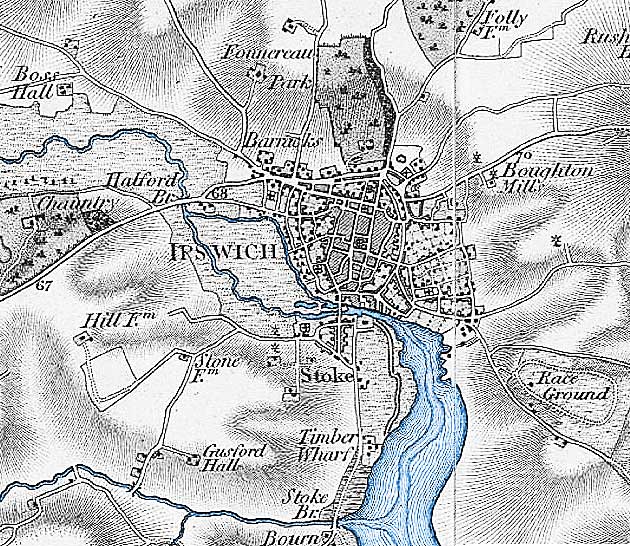

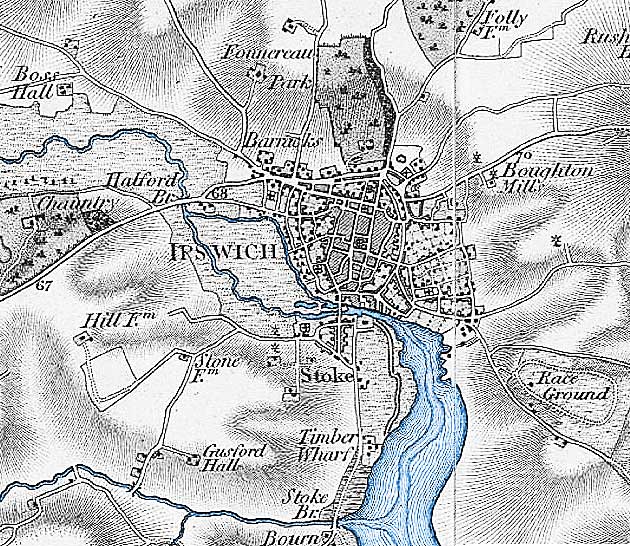

1777 Chapman and Andre map

1777 Chapman and Andre map

Detail above is from www.VisionofBritain.org.uk

We know that the

Wet Dock and New Cut were created in 1842, so this map must pre-date

this.

Above, the natural dock, pre-Wet Dock enclosure, at lower right

and the narrower

river to the west of Ipswich which splits into two between Stoke Bridge

and Handford Bridge at upper left. Rober Malster (see Reading List Ipswich

A-Z) tells us that "the one that flows along the edge of the

valley towards Handford Mill is usually marked as the Gipping, while

the main channel flowing down the middle of the valley is often

delineated 'The salt water'. The more northerly channel is clearly

artificial, but it is of great antiquity: it already existed in AD 970.

Archaeologists have found a Roman settlement beside it, and the channel

may have been excavated during the Roman occupation of Britain [c.AD285

- 480]... There is some evidence that until the 18th century the whole

river from Rattlesden [near Stowmarket]

to the sea was known as the

Orwell, and the stream flowing into Stowmarket from the north was

considered a tributary; there is an Orwell Meadow in Rattlesden." Today

we consider that northward tributary to be a continuation of the

River Gipping, with its source near the village of Gipping; we

call the

tributary from Rattlesden to the Gipping the River Rat or the

Rattlesden River.

One or two points arise from looking at this map. Handford Bridge is

mistakenly labelled 'Halford Br.'. The Chantry to the west is labelled

'Chauntry'; the Artillery Barracks at

Barrack Corner on Norwich Road are labelled. Today's Christchurch Park is labelled

'Fonnereau Park'. Pairs of windmills are shown either side of the road

on Belstead Road hill and on Albion Hill

(the latter labelled 'Boughton Mills', perhaps named after the owner).

The 'Race Ground' at today's

Racecourse and Gainsborough housing estates is labelled to the east.

Within Ipswich, the split in the river is sometimes labelled 'River

Gipping' to the north and 'River Orwell' to the south; interestingly

this practice is continued on modern computerised maps available on the

internet. The Gipping navigation met demands for narrow boats to carry

materials and goods between Stowmarket, Ipswich and the sea. However,

anyone walking along the Gipping River Path (much of it along a horse

tow-path) will learn from the information panels that the use of the

river by boats goes back centuries. The River

Gipping was officially closed as a navigation in 1932. The area between

the two river branches was Portman's Marshes.

Marshes

Areas to the south and the west of the natural harbour provided by the

River Orwell were particularly known for their marshy character. The

extensive waterlogged land provided a natural defence for the town,

making it very difficult to launch an attack on foot or on horseback.

The river itself provided a defence, too. We have to imagine the river

as much broader and shallower around the original fording point used by

the Anglo-Saxons (and probably the Romans before them) from Great Whip

Street in the south and Foundry Lane in the north (another route for

the ford into Turret Lane has also been proposed). The Church of St Mary-At-Quay was famously built on the

marshy ground where the spring waters from the surrounding hills pooled

on its way into the river. At the time of Cardinal Wolsey, when his

Water Gate into his ill-fated College

was built (c.1528), the river revetment (strengthened bank forming a

quay) was around the line down the middle of College Street. This is

but one example of the way in which the broad, marshy areas were

drained and reclaimed and the riverside gradually moved back to its

present location on the northern quays of the Wet Dock. John Norman

tells us that the use of ballast (usually sand, gravel or broken stone)

by

trading vessels to ensure stability while sailing empty aided this

process. When docking and prior to loading of the cargo, the ballast

was removed from the holds and dumped at the river bank. Many

repetitions of this process would hasten the extension of the hard

quays and the narrowing of the natural harbour.

Mention of the marshland and rivers as natural deterrents to attack

brings up the thorny question of the rampart-and-ditch

town defences. Stephen Alsford's excellent website History of

Medieval Ipswich (see Links) tells us:

'The line [of the ditches] was clearly suggested in the topography of

the streets into the 19th century (although less so with late

20th-century redevelopment), including street names like Tower Ditches

and St. Margaret Ditches. According to a note in one of the Ipswich

Domesday Books, the ditches were dug in 1203; but this does not rule

out the effort simply being an enlargement or extension of an earlier

line of defence. There are fairly frequent references to grants of

parcels of the town ditch, particular along the northern boundary,

where they are sometimes referred to as the "great ditches of the

town". Walls are far less commonly mentioned and their extent is

uncertain. In 1302 a burgess was granted a lease of part of the

ditches, for 6d. a year, to be voided if the town were ever enclosed by

a wall. We hear of town wall in St. Margaret's parish in a grant of

1315, and in St. Mary Elms parish in 1323. A change had occurred

between the compilation of a custumal in 1291 and its translation into

English in the fifteenth century, since the former refers to a

watercourse called "Botflood" (the flooded town ditch?) passing along

the side of a road, while the latter refers to it running alongside the

wall. What wall-building there was may have focused on areas where the

ditches were weakest and may never have proceeded to creation of a

continuous line; the eastern and western sides of the borough clearly

had walls, but it is less certain that the northern perimeter did.'

Alsford depicts, to the east, the

defences as running from Common Quay on the Wet Dock northwards up

Lower Orwell Street, [probable site of the East Gate], Upper Orwell

Street past Majors Corner, then westwards along Old Foundry Road (St

Margaret's Ditches), [site of the North Gate], Tower

Ramparts, [site of the West Gate], then

southwards down Lady Lane and the former

Tanners Lane (now beneath Civic Drive) as far as Friars Bridge Road. The last section

has changed dramatically due to 'modernisation' in the 1960s (see 'Ipswich tomorrow'). It is assumed that

there was no need for an earthwork south of this via Greyfriars Road to

Stoke Bridge because of the rivers and

marshes, water providing a natural defence. Marshland provided ideal

grazing for animals. For the six hundred years, between the granting of

the Royal Charter in 1200 and the Municipal Corporations Act 1835, the

town was run by Bailiffs, Burgesses, and Portmen (the 'great and the

good' of the town). The name Portman's Marshes recalls the first

Portmen of Ipswich who were granted a meadow named Odenholm or

Oldenholm on which to keep their horses. Others have said that they had

the right to graze their cattle there – perhaps both are true.

The regular tidal inundation of the the channels and

gullies of the marshes enabled this collected water to

be used to drive the Tide Mill alongside Stoke Bridge. After the

Municipal Corporations Act 1835 the marshes passed to

Ipswich Corporation and municipal buildings have been built upon the

land ever since. In fact Pennington's map of

1778 shows the legend: 'Land belonging to the Corporation' right

across Portman's Marshes. What was once an area of little practical

use, this large area was eventually drained and developed to provided

land

for:-

1. the building of the town's first coal-fired power

station in today's Constantine Road (which also burnt the town's

rubbish to generate power);

2. a Sewage Pumping Station (marked on the 1902 map)

pre-dated the power station and was situated nearer to the river on

Constantine Road;

3. the related electric tram depot (stillused by Ipswich

Buses) next door;

4. Portman Road football ground which from 1855 was the

home of East Suffolk Cricket and more recently an internationally-known

location; Ipswich Town Football Club have been leasing the ground from

the Borough since 1936;

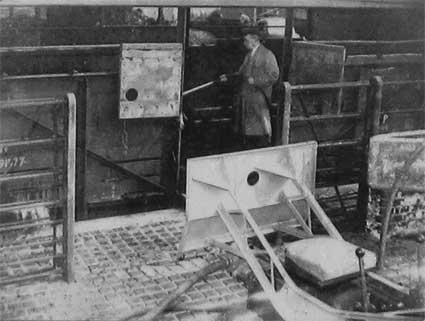

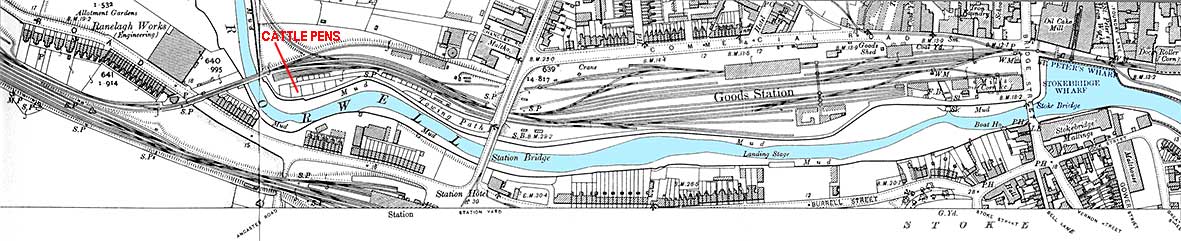

5. the new Cattle Market, which had moved from the top of

Silent Street (see our Old Cattle Market

page) in 1856 and occupied a substantial area of land, either side of

Princes Street, and operated here until January 1985; scroll down to

the foot of this page for the old railway cattle pens;

6. the Drill Hall, where Ipswich’s Volunteer Reserves met,

was on the junction of Friars Bridge Road and Portman Road;

7. Commercial Road was the first street to be constructed

in the 1850s, providing access to the Railway Goods Yard;

8. Cardinal Park with its car park, cinema,

clubs, bars and

restaurants was built on the former Ipswich Corporation depot site

between Commercial Road (renamed Grafton Way) and Grey Friars Road;

9. most recently, Ipswich Borough Council moved its

offices from the CIvic Centre to Grafton House in Russell Road

(opposite Suffolk County Council's offices in Endeavour House) in 2005.

[Information from John Norman's Ipswich Icons column.]

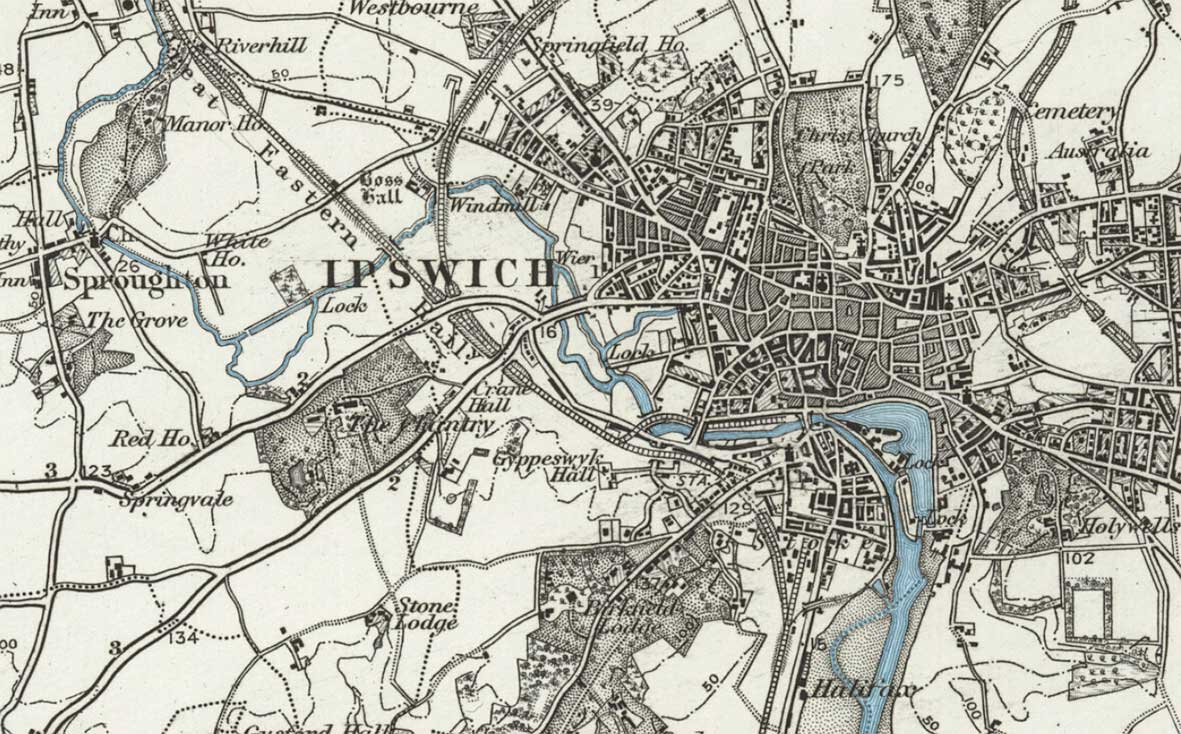

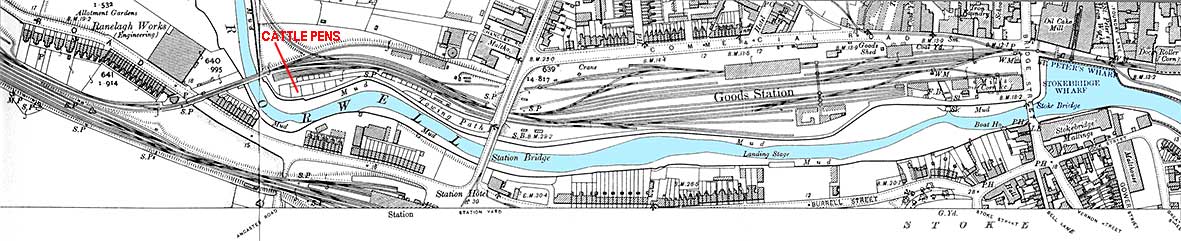

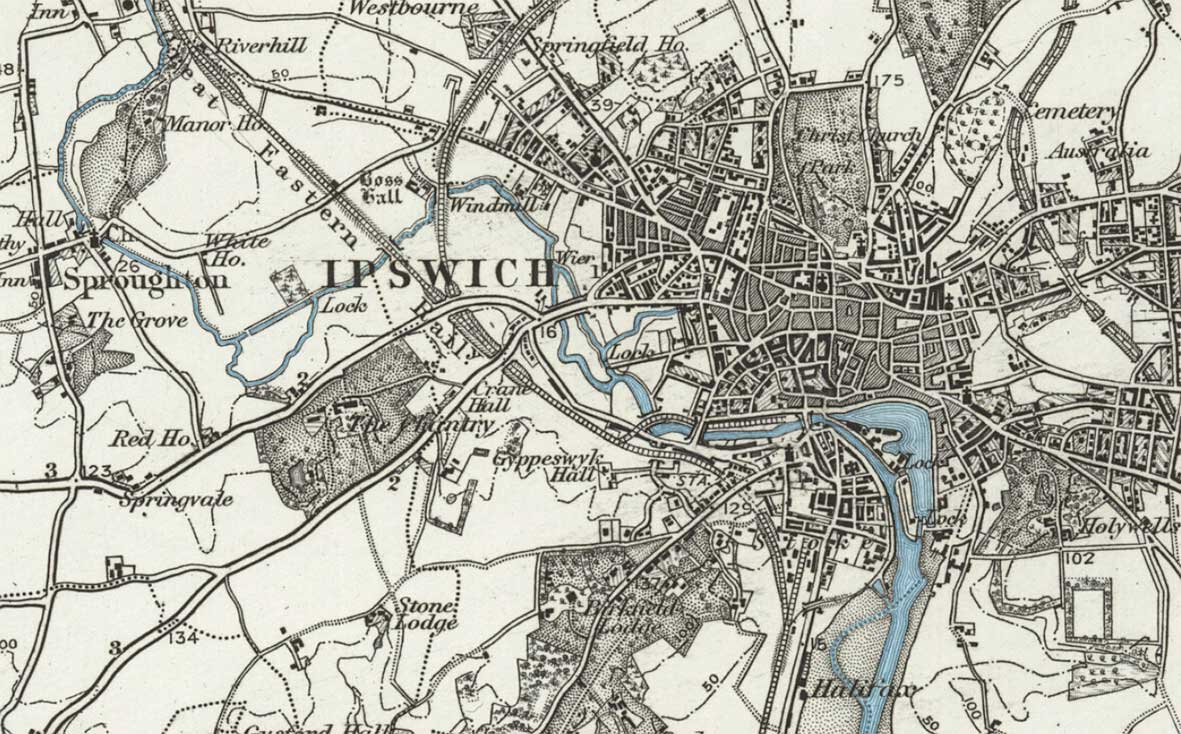

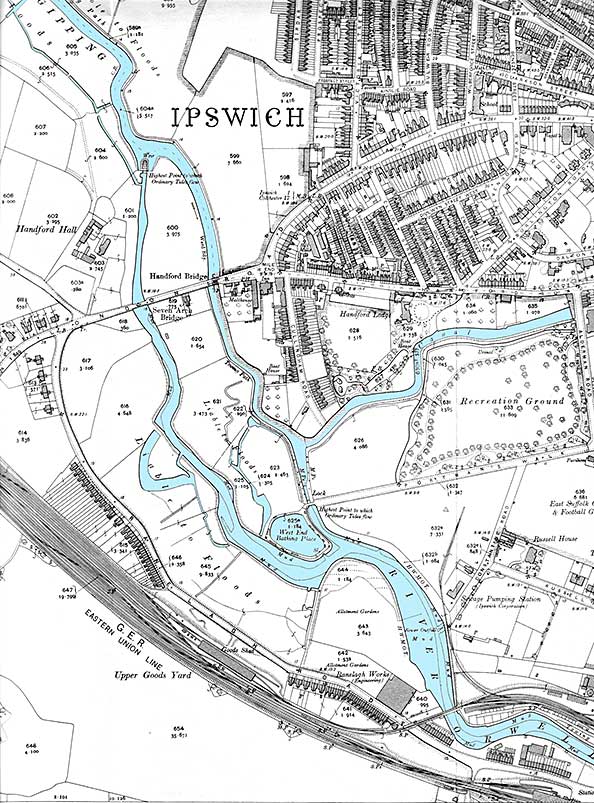

1896 map

1896 map

The 1896 map shows the post-Industrial Revolution river system

(marked in blue). Above the legend 'Halifax' and on the west bank we

see the Griffin Wharf branch railway crossing Wherstead Road to reach

the river. North of that is the enclosed Stoke Bathing Place. The Wet Dock, opened in January

1842, shows two locks, one off New Cut and the one we know today at the

south. The lock half-way up New Cut was never popular

with mariners: the sharp turn required to move a vessel in line with

this lock – particularly when approaching from the north-west – led to

some collisions. The south lock was built between 1869 and 1871 to

remedy this problem. The Promenade with its avenue of lime trees was

the place to be seen on a summer Sunday afternoon stroll down to the

'Umbrella' shelter and Pegasus statue, with views over the river to Hog

Highland (south of

the Cobbold brewery), it existed

between the old and new locks. In 1904 Timber Quay was built over the

inner end of the old lock making it unusable. There

were originally no quays between the Wet

Dock and New Cut, the majority was taken up by a 'mill pond' (clearly

shown on the above map) which provided a head of water used to operate

George Tovell's

roman cement works. The pond, later used for storage of timber, became

a branch dock, but was filled in during works on the Island in 1923-5.

Tovell's Wharf was constructed on the north side of the Island.

Additional notes on the 1896 map.

The branch line from the Great Eastern Railway can be seen on the map

running across

a level crossing on Ranelagh Road and over the river by

a

small bridge, then

round to goods sidings and the tramway which ran all around the Wet

Dock and

beyond. Parts of these trackbeds can still be found, but many rails

have been lifted. Another point of interest is the area at the southern

end of Sidegate Lane (upper right of the map) labelled 'Australia'.

This would be around Hutland Road and Meadowvale Close (the site of St Helens Barracks). But why

'Australia'? Probably a similar 'frontier' feature to California. Interestingly at this time

Belvedere Road with its bridge

over the Felixstowe branch line is shown in dotted lines. See

our Friars Bridge Road page for more

on Greyfriars and the Little Gipping.

Where Gipping becomes Orwell

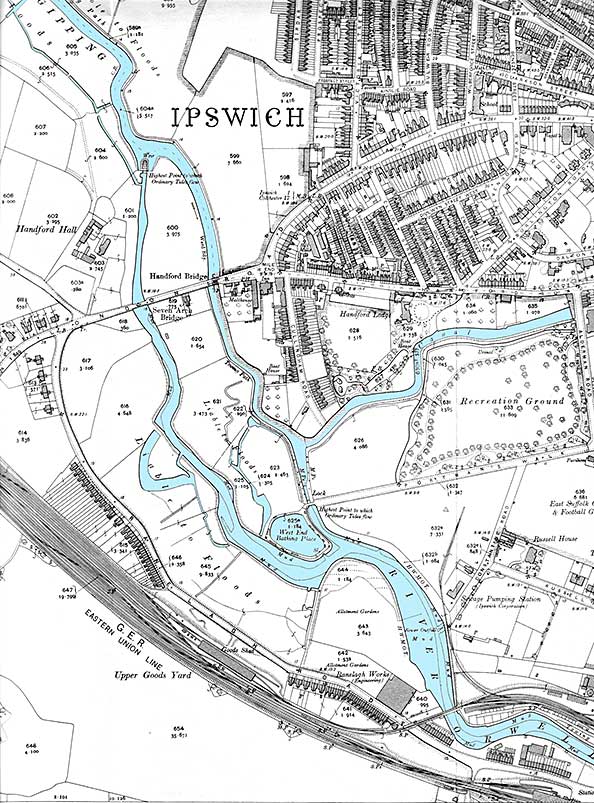

The legend 'Wier' [sic] north of Handford Bridge on the 1896 map

is the

Horseshoe Weir.

It is clearly visible on the 1902 map (below) because it is drawn in –

north of 'Seven Arch Bridge (now replaced) carrying London Road – and

labelled:

'Highest Point to which Ordinary Tides flow'. It is

generally agreed that at the

Horseshoe Weir, or just below it, the freshwater River Gipping meets

the brackish water of the River Orwell, dependant on the strength of

the spring tides. Note also on the 1902 map

the 'West End Bathing Place' (see 'Bathing places' further down this

page) at the south of the long thin 'island' and at the west end of

Portman's Walk (now renamed Sir Alf Ramsey Way); swimmers accessed the

pool

via a footway across the lock gates where we find a repeat of the the

label: 'Highest

Point to which the Ordinary Tides flow' on this leg of the river. So,

in summary, the point

where the freshwater Gipping meets the brackish Orwell moves between

the lock and the Horseshoe Weir, dependant on the tides.

Just north of the lock is

the arm of the Alderman Canal. In the past a further section of the

Gipping existed, sometimes known as the “Little” or “Upper” Gipping,

thought to be a manmade cut which flowed east from the Gipping in

Ipswich parallel to Handford Road, before dropping south-east, parallel

to what is now Civic Drive, Franciscan

Way and Greyfriars Road to rejoin the River Orwell at Stoke Bridge. Only a section of this river

now remains, known as Alderman Canal reaching east to Alderman Road,

with a return ditch flowing below Alderman Canal, under Bibb Way,

through a reedbed to Sir Alf Ramsey Way (Portman's Walk) where it is

piped underground

to the River Orwell exiting in the vicinity of Constantine Weir. The

return ditch was presumably dug when the section south-east from

Alderman Road was stopped up in Victorian times.

The

River Orwell is easy to trace because it follows much the same line

today: the south western edge of the marsh. Following the 1953 floods,

the river was canalised, sheet piles driven into both banks to stop the

town flooding – not particularly attractive at low tide. Since the 1902 map West End Road was built from

Commercial Road, crossing London Road, and into Yarmouth Road (the

1930s Ipswich By-Pass). These roads now occupy the long thin island

between the two rivers. There is a

footpath alongside the river from Stoke

Bridge, under Princes Street Bridge, the Bobby Robson Bridge and as far

as the weir close to West End Road. As it approaches Yarmouth Road it

splits, the

route straight ahead becomes the tidal Orwell but the fresh water

diverts left under Yarmouth Road, under Handford Road bridge and across

Alderman Road recreation ground to the site of Handford Mill (at the

top of Alderman Road). From there, it is underground, contained in a

culvert (Little Gipping Street marks the line). It crosses the site of

the former Portman Road cattle market, under Friars Bridge (clearly

shown on Edward White’s map of 1867) where it provides evidence of its

presence behind the Greyfriars car park with an elongated hump in the

ground, which crosses Wolsey Street, close to the back gate of

Jewson’s. The Gipping discharges into the Orwell just above Stoke

Bridge appearing under the Skate Park. When the Gipping was made

navigable in 1793, a lock was cut between the two rivers near West End

Road (Handford Lock). The lock gates have gone and a flow control gate

has been installed, holding the waters of the Gipping at a constant

level up to Sproughton. The waters of the Gipping cascade, waterfall

style, into the Orwell.

1902 map

1902 map

Note also, on the 1902 map, the complex layout of the 'G.E.R. Eastern

Union Line' – how nice that

the original name of the Eastern Union Railway

from Colchester to the original station in Stoke is still used here;

the first EUR train ran in 1846, becoming Great Eastern Railway in

1862. As the goods spur comes off the main line, crosses Ranelagh

Road by a level crossing (vestiges visible today), crosses the Orwell and turns

towards the docks, another smaller line comes back westwards and

northwards away from the goods sidings to run beside the opposite bank

of the river, over the cul-de-sac of Constantine Road and round behind

the 'Ipswich Corporation Sewage Pumping Station' and the future site of

the power station and tram/bus depot. One assumes that the main purpose

of this branch was to supply coal to the power station which generated

electricity for the trams and trolley buses and also for residential

use. At the time that this map was published, work had only just begun

on building the power station (Constantine

House) and tram depot.

Handford Mill on the Alderman Canal

Handford Mill was a

water-powered mill standing at the east end of this stretch of water,

close to Handford Road (see Street name

derivations). It is believed originally to have been fed by a

stream

running down from the Anglesea Road area, but an artificial channel was

dug to bring water from a new weir built on the Gipping some way above

Handford Bridge. This channel was certainly in use when the bounds of

Stoke were set down in AD970; it is possible that this was dug by the

Roman occupants to bring water to a mill on or near the site of

Handford

Mill (the first written record of which is found as

early as the 13th century). In the 19th century the mill was used to

crush seed to extract oil; no traces of it apparently now exist. A

valve

prevents

flow between the River Gipping and Alderman Canal. The Alderman Canal

now only receives surface run-off from its immediate surrounds

(principally properties along Handford Road). The Rivers Orwell and

Gipping were formerly navigable by means of locks and as recently as

the 1970s boats could be hired from Wrights Boatyard, Cullingham Road (on the

River Gipping,

just north of Alderman Canal). In addition to boat hire, the Yard

offered boat manufacture and repair/maintenance.

1938 image

1938 image

Above: the Little Gipping (Alderman Canal) with Handford Mills in the

lower part of the 1938 aerial photograph. Cullingham Road runs from

left to right a little higher up. At the junction with Handford Road,

London Road curves round to meet it.

Little Gipping &

Great

Gipping

Streets, Canham Street

2016 images

2016 images

'LITTLE GIPPING STREET' 'GREAT

GIPPING STREET' are located in a small housing estate to the west

of Civic Drive and delineated by Portman

Road, Civic Drive and the

large car park block of the Axa offices. Presumably the

Alderman Canal would once have continued in a loop round to join the

main river just west of Stoke Bridge. This watercourse still exists as

the Little Gipping River which runs underground and in culverts beneath

these roads, under Friars

Bridge Road and south eastwards

under a 'bump' in Wolsey Street (see photograph below), then between

the Jewson block and the

Cardinal Park gym and restaurants (you can see the cover over the

culvert where wheelie bins are stored on the photographs below) to an

outfall into the Orwell. (N.B. Great Gipping

Street is also home to the bicycle symbol

pressed into the railings.)

2021 image

2021 image

Above: nearby is Canham Street, which joins Portman Road and Great

Gipping Street in an arc. At the latter junction is an older street

nameplate on the bungalow wall, a style seen elsewhere in the town and

probably in cast aluminium. The superior 'T' is characteristic of this

style (perhaps early 20th century). Compare with other styles on the Street nameplates page. See the Street

names derivations page for the derivation.

Photos

courtesy Bob Markham

Photos

courtesy Bob Markham

Below: Wolsey Street shown in the 1960s from the Ipswich Society's

Image Archive (see Links) – "[View] from the

Cecilia St (left) junction after partial clearance of

the area. The Zulu Inn stood on the left hand corner in front of St

Francis Tower. St Nicholas Church tower can be seen over the white

painted building in the right background and part of the Greyfriars

development and St Francis Tower on the left. The slight hump in the road was a result

of the Little Gipping river being bricked over and used as a sewer in

Victorian times. It discharges into the main river in St Peters Dock

just upstream of Stoke Bridge. This hump in the road still exists just

to the north of Cineworld Cinema at the junction of Cecilia St, Wolsey

St and Quadling St." (see our Lost trade

signs page for an earlier

photograph showing the Zulu Inn with the Greyfriars muti-storey car

park and St Francis tower under construction behind.)

Photograph

courtesy The Ipswich

Society

Photograph

courtesy The Ipswich

Society

Below: two outfalls from underground conduits into the River

Orwell,

photographed from Stoke Bridge.

2018

image

2018

image

The Ipswich Brook

A

similar outfall exists for the Ipswich Brook which is the underground

version of the waters which flowed for centuries down Northgate Street,

Upper and Lower Brook Streets; it flows under Star Lane to reach the

Orwell and eventually the sea. The Ipswich Brook existed as a

watercourse carrying the copious spring water and surface drainage

water

which flowed down the sides of the 'dish' of Ipswich to reach the main

river two thousand years ago. Another brook started

high up the hillside at the site of today's Warrington Road flowing

down to help power Handford Mill...

The water-mills. See

our Friars Bridge Road page for much

more on these mills and the way in which water has been managed in the

town.

The Mill River: a 'lost' river in

Ipswich (also, the pioneer

archaeologist Nina Frances Layard)

John Norman's column in the local press often provides surprises

and this 'Ipswich icons' (Anglo Saxon cemetery in Hadleigh Road,

May 2016) is particularly germain to a page about water in Ipswich.

"There is a dip in Foxhall Road, a depression that is in geographical

terms the start of the Mill River.

No sign of water just here but the valley runs south and then east,

across Bixley Road and then parallel with Bucklesham Road, where the

first surface trickle is encountered. It continues onto Purdis where it

forms ponds on Ipswich Golf Club’s course. On to Foxhall then Newbourne

where it gets a name on the map§, and finally to Kirton

Creek, where it discharges into the Deben.

In a mere eight miles and a few feet of descent the trickle has become

a small river with a wealth of wildlife but it is at the Ipswich end

that our journey starts. Opposite Henslow Road today is a children’s

pocket park, entered through marching band-shaped gates of fascinating

interest.

Foxgrove Gardens is an estate

of 288 flats and town houses, built in

the late 2000s by house builder Barratt Eastern on the 14-acre site

previously occupied by Bull Motors and Celestion Speakers. Prior to

this it was a brickworks, and a considerable number of years before

that the very earliest Europeans lived here. They were hunter

gatherers, chasing animals, collecting berries and living an existence

lifestyle. They lived here in the Palaeolithic period – about half a

million years ago. How do we know this?

Foxgrove Gardens is an estate

of 288 flats and town houses, built in

the late 2000s by house builder Barratt Eastern on the 14-acre site

previously occupied by Bull Motors and Celestion Speakers. Prior to

this it was a brickworks, and a considerable number of years before

that the very earliest Europeans lived here. They were hunter

gatherers, chasing animals, collecting berries and living an existence

lifestyle. They lived here in the Palaeolithic period – about half a

million years ago. How do we know this?

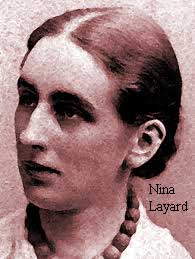

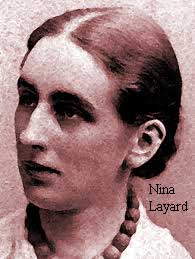

It is primarily due to the dedicated work carried out by an Edwardian

lady, Miss Nina Layard. She was born in Stratford, Essex, in 1853,

lived in a number of different places before she moved to Ipswich when

she was 36. Nina had always had a fascination for the earth sciences

and in 1898 she began studying Ipswich’s archaeology.

She was given

some flint tools found in Levington Road when the houses there were

being built (1894-1901). These were Nina’s first positive indication of

the Palaeolithic occupation hereabouts.

in 1853,

lived in a number of different places before she moved to Ipswich when

she was 36. Nina had always had a fascination for the earth sciences

and in 1898 she began studying Ipswich’s archaeology.

She was given

some flint tools found in Levington Road when the houses there were

being built (1894-1901). These were Nina’s first positive indication of

the Palaeolithic occupation hereabouts.

At the start of the 20th Century when Valley Brickworks was almost

worked out, Nina was taken to the site to be shown what

the foreman had

identified as flint tools. Flints are a nuisance in the brick-making

process and are thrown aside by the labourers digging the clay. As well

as the samples she had been shown, she found other

worked flints lying

in the grass nearby.

She returned to this brickyard again and again where she uncovered more

flint implements, mainly hand axes, carefully recording their location

and the depth at which they were found. It became clear there had been

some silting-up of the valley since these tools had been dropped and

some were buried 10-12ft deep. In total there were some 250 finds, of

which in excess of 50 were hand axes.

The finds at Foxhall Road

proved to be of national importance; they

confirmed not only that there were humans in Ipswich in the

Palaeolithic period but that they enjoyed life on the plateau above the

Orwell valley. Nina also visited Trinity

Brickworks in Cavendish Street and the Dales brickfield hoping to

find similar objects but there were very few flints in these locations.

Her most significant discoveries were in Hadleigh Road in 1905, the

site of an Anglo Saxon cemetery (with 160 graves). She had excavated

the Hadleigh Road site with the help of men engaged by Ipswich Borough

Council on a ‘workfare scheme’ (opportunities for the unemployed) just

ahead of work beginning on a road widening scheme.

The finds at Foxhall Road

proved to be of national importance; they

confirmed not only that there were humans in Ipswich in the

Palaeolithic period but that they enjoyed life on the plateau above the

Orwell valley. Nina also visited Trinity

Brickworks in Cavendish Street and the Dales brickfield hoping to

find similar objects but there were very few flints in these locations.

Her most significant discoveries were in Hadleigh Road in 1905, the

site of an Anglo Saxon cemetery (with 160 graves). She had excavated

the Hadleigh Road site with the help of men engaged by Ipswich Borough

Council on a ‘workfare scheme’ (opportunities for the unemployed) just

ahead of work beginning on a road widening scheme.

Ipswich should have been recorded as a site of national importance but

the First World War denied Nina the recognition she deserved and later

she was upstaged by discoveries at Pakefield, Suffolk and Happisburgh

on the Norfolk coast (indicating humans have lived in East Anglia for

almost one million years).

In 1914 Valley brickworks was sold,

and in 1922 Bull Motors moved to the site. By 1968 factory space had

become available and this was occupied by Celestion Speakers. The

Celestion factory closed in the 1990s and Bull Motors moved to

Birmingham in 2000 thus the site again became available for human

occupation."

[§In

fact a well-known digital map provider shows and names the 'Mill River'

in Bixley Heath Nature Reserve as it enters Ipswich Golf Club; it is

soon joined by the 'Mill Stream' flowing south from the Foxhall Stadium

area, then on, growing in size it flows beneath the A12, through

Brightwell,

under Watermill Road at Newbourne to be joined by the stream that

visitors to Newbourne Springs Nature Reserve will know well, swelling

it in size before it eventually reaches the River Deben.]

In a way, the most surprising thing about John's article is that

a river in Ipswich flows 'the wrong way' – not down the surrounding

hills to the River Orwell, but the in the opposite direction to its

sister river. He sends this additional information

about the course of the Mill River:-

'The Mill River doesn't really flow the wrong way (as ageing

cyclists will know, the railway bridge on Foxhall Road is the high

point, down hill to the Orwell cycling west and downhill to Henslow

Road cycling east. The Mill River marks an ill-defined valley

from the pocket park Foxhall Road to Provan Court (off Bull Road) under

the railway, (the railway builders ensured it didn't flood the

Felixstowe Line) then into Malvern Close off Felixstowe Road.

Mill River originally crossed into Felixstowe Road at about The Haven

public house (where I assume it is still in a culvert) but then back

between the houses to the north (note how Margate Road drops down at

its eastern end). Under the railway again and into the pumping

station in front of the Children's Hospice (EACH Bixley Road).

Bungalows in Bucklesham Road have a very long front gardens, the Mill

River at this point was in a deep valley, the stream is now in a

culvert

and the valley filled (with Green Sand from Crane's Foundry).

The stream doesn't actually appear on the 1904 OS until the Gothic

Cottage on Bixley Heath from where its route is known (and visible);

the stream at the bridge on Bixley Heath can be surprisingly full after

heavy rain.'

Springs, conduits and a fresh water

supply to the

town

Springs

"Ipswich is fortunate that the River Gipping has carved its way down to

the Chalk – at about 85 million years old, the oldest and lowest of the

surface rocks here. It provides a stable foundation for the tall

buildings which line the Waterfront, for the Orwell Bridge and for our

new flood gates. It also supplies much of our modern water supply.

Younger London Clay (Eocene, 54 million years old) and Red Crag

(Pliocene, 2¾ million years old) sediments overlie the Chalk and

outcrop higher up in the valley sides. The permeable Red Crag holds

water, which gushes out as springs where it meets the impermeable

London Clay below. Thus Christchurch and Holywells Parks have a

constant and plentiful supply of natural water for their various lakes,

ponds and canals, issuing from the Red Crag/London Clay junction.

"Lining the river banks and sitting on top of the Chalk is a series of

gravel terraces. A gift of the Ice Age when torrents of melt water

flowed down the valley, these formed level, well-drained land for the

first Anglo-Saxon settlement here. It is no coincidence that Ipswich is

the oldest continuously settled town in England. It has, arguably, the

best settlement site in the country and the Anglo-Saxons, arriving here

in the early 7th century, recognised this and stayed, thus laying the

foundations of our town. Building their early settlement at the head of

the Orwell estuary, a navigable 15 kilometre inlet of the North Sea,

they chose the sunny, north bank, with its plentiful water supply from

the crag springs. The broad terraces and gentle slopes have provided

room for growth into the large town we have today, which still benefits

from its sheltered aspect." (Extract from Caroline Markham's article Foundations in The Ipswich

Society's book Ipswich: a town to be

proud of, 2019.)

A crucial aspect of human (particularly urban) habitation

is the availability of fresh water to the inhabitants. Given the

advantages of the clean springwater in the hills around the

Ipswich,

it was not too difficult to arrange pipework into the town centre.

However, the surplus water found its own courses down the bowl-shaped

terrain towards the town

centre and eventually into the River Orwell. Radial streets from the

town centre provided ideal water courses and one of the longest

journeys for spring water came from around the Cauldwell Hall estate

(marked today by Cauldwell Hall Road

and Cauldwell Avenue) on the east of the town which became the

Cauldwell Brook. Many early street names reflected the relationship to

water.

The Cauldwell Brook & The Wash

Spring Road did not really exist in the mid-18th century; it was known

as 'the old hollow way into Ipswich' and was gated at the foot of the

steep hill near today's St Johns

Road junction, becoming no more than a footpath uphill through meadows.

The upper section of today's Spring Road (roughly from the Cauldwell

Hall Road crossroads eastwards to Lattice Barn) was 'the Old Road'. The

water flowed down 'the old hollow way into Ipswich' and

pooled as it became St

Helens Street, called variously 'St Helens Wash' and 'Great Wash Lane'

in the past, such was the volume of water during rainy periods.

Additional water flowed down Water Lane (today's Warwick Road) carrying

flows from Albion Hill (Woodbridge Road). This

undrained area at the site of today's Grove Lane junction was

impassable by wheeled vehicles at this time. All traffic used 'The Way

to Woodbridge' (later Woodbridge Road) to leave the town and that way

would have taken them along today's Rushmere Road, the section to

Lattice Barn was yet to be built by the Turnpike Trust. [See our Barclays/tollhouse page for more on this.]

Our H.W. Turner page shows a

flooded St Helens Street in 1911 with shop staff armed with brooms to

try to sweep the waters away from their thresholds. Near to today's

Argyle Street was Wells Street

(commemorated by the 20th century Wells Court flats development),

again an indication of the dominance of water to the inhabitants. For

centuries in Ipswich there was little paving and no tarmacadam road

surfaces, so the water carved its way into the roadways and created mud

and pools of clay and liquid horse manure which cannot have aided

passage by said horse and cart

(which also churned up the roads, no doubt).

The

Spring Road waters continued past the present-day Argyle

Street/Grimwade Street

crossroads (Borough Road,

later Grimwade Street, originally

only ran as far north as Rope Walk – the prison yard was

beyond), past the Ipswich Gaol (behind County

Hall), to Major's Corner.

A sharp turn left into The Upper Wash and

Lower Wash (Upper and Lower Orwell Streets), having crossed the Spread

Eagle/Orwell Place crossroads where stepping-stones (stepples) were

installed to enable the poor pedestrians to cross without getting their

feet too wet or muddy; indeed Orwell Place was called 'Stepples Street'

at this

time. See Street name derivations for

more on these street names. The 'Common Wash' around Lower Orwell

Street was an area where people washed their clothes. Eventually all

this water pooled in the marshes above the northern quays of the dock,

eventually seeping into the Orwell. It seems that this would have been

the worst place to build a medieval church so the central one of the

three dockland churches, St Mary-At-Quay,

was duly constructed there and has suffered the structural consquences

ever since; in

2016 the building has been saved as a well-being centre and the walls

and stone columns repaired and cut off from the destructive rising

damp.

From leaving the 'Cauld Well' the water dropped about 180 feet to the

river.

Of course, at a time of little sanitation and open sewers in the

medieval streets of Ipswich, the inhabitants used the flowing water to

carry away horse and human filth and other waste. The spring

water, once so clean and clear, was anything but by the time it reached

the river. Even after

much of the spring water flow was piped underground in the

20th century (see the following paragraphs), it continues to trickle

from hillsides, for

example in Grange Road and Alexandra Road (see images below), and the

lower-lying streets

of Ipswich experience flash flooding in extreme weather conditions.

Inhabitants of Spring Road have had their cellars flooded and they

really know that there is a deluge when the heavy cast iron drain

covers in the roadway are lifted up by the force of the water from the

overwhelmed underground pipes.

2016 images

2016 images

[UPDATE summer

2016: above – spring water flows in Alexandra Road,

close to the junction with

Warwick Road (formerly Water Lane). The main flow to the left partly

trickles

down the gutter drain, the rest moving over the road and some distance

down the gutter of Warwick Road. The cracks in the road surface yield

more water; all the wet areas are turning the road surface green.]

'It is recorded that in 1463, a ship sailed from Ipswich

with men and

stores for war. Amongst the stores were 8 ‘pipes of Caldewelle’,

containing fresh water brought from the springheads at Caldwell. As

early as the 15th century the Blackfriars

Priory were bringing the water in through wooden pipes as by the

time the spring water reached the town, it become more and more

polluted as domestic and trade waste was swept in to the water course.

The pipeline, the source of which was probably the

springs at Cauldwell Hall, was later to be utilized by the Corporation

for general consumption.' For a small fee, the town authorities allowed

the water to be extracted along the route but as Dr J. E. Taylor's

notes

in his description of ancient Ipswich in 1555 some one took the

entrepreneurial spirit a bit too far. Edmund Leeche, of St Margaret

Parish, seeing the water was so abundant, decided without prior

permission, to erect a water wheel upon the course of the Caldwell

Brook. By stopping the water, he flooded his neighbour's gardens. It

was ordered that “… the said Edmond shall take away his floud-gate and

and mill-wheel before Mich. [Michaelmas] next, under £20 pain, to be

levied upon his goods and chattels, and that no person shall henceforth

keep any watermill there for the grinding of corne”. This order was

treated either with contempt or neglect, for five months afterwards, it

is stated that “Edmund Leeche, not having taken the floud-gates and

mill-wheel upon the stream from Caldwell Brook, it's ordered that he

does so before Christide, under peril of £20 forfeiture and for the

fine already set upon him."

In their Golden Jubilee Booklet of St. John the Baptist Church produced

in 1949, Miss B. Hurley and Miss H.K. Garrett wrote of St Helens Street

in the 1850s, then known as Caldwell Street, as possessing a gaol and

two leper hopitals and of Spring Road as being well named as it was "…

but a sandy often swampy bridle path. As late as 1865 when young

residents of Cauldwell Hall were returning from Balls, the cabbies

refused to drive any further than the viaduct in Spring Road lest their

wheels stuck in the mud." During the late 19th and 20th centuries

rather than running down through the 'Wash' to the River Orwell, the

springs were piped in to a reservoir beside the railway viaduct on

Spring Road for distribution to the town. This reservoir was demolished

in 2007 and student accommodation built on the site' [Source – Gooding,

A: The history of Cowper Street,

Ipswich. See Reading list]

Christchurch Park. The level

rises by about 38 metres from the Soane Street entrance to the

northernmost Park Road entrance. In keeping with the bowl-shaped

topography of Ipswich, this results in plentiful spring water in the

park, as found elsewhere in Ipswich. The finest public park in the

town, running down almost to the town centre, is noted for its lush

vegetation and ponds. The latter – probably in different configurations

– probably date back to the fishponds of Holy Trinity Priory,

which stood on or near the site of today's Christchurch

Mansion, although the Round Pond may be 17th century. See our entry

for Dairy Lane on the Street name

derivations page for an insight into water management in the park.

Holywells Park ('Hollow

well') tells its own story of water in its name. We

include an early 1930s map of the park on our Bishops Hill page, showing all the bodies

of water including much of the moat around the Bishop's Palace – which

gives the hill its name. See below for an explanation of the so-called

'Holy well': C. Holywells.

Ipswich as a spa town?

With the pure spring water, plentiful throughout the history of

Ipswich, it has puzzled us that the town did not develop as a spa, as

did Felixstowe (the 'Spa Pavillion'). It has been suggested that

Ipswich was just too industrial

to attract the country gentry (in the same way that the wealthy and

Middling Classes gravitated towards Bath at the time Jane Austen was

writing her novels). In a maritime port town associated with

shipbuilding,

rope-making, brick and tile-making, tanning, phosphate manure

manufacture, staymaking (whalebone

corsets), heavy engineering, malting and brewing and so on, perhaps it

was just too trade for the

toffs. Here are some of the aqueous candidates...

A. St Georges Street

In the second half of the 17th century, a spring was discovered

on St

Georges Street. This would have been one of the many springs which

still surround the town; perhaps the location close to the town centre

and to the (now lost) Church of St George made it of some importance.

However, Ipswich already had a spa: the ‘Ipswich Spaw Waters’ in St

Margarets Green (see B). The idea of opening another spa was

rejected.

[This

text is repeated on our page on The Unicorn,

as it relates to 'taking the waters' and the development of a bottled

mineral water business, Talbot's.] The medicinal but

foul-tasting water of the spring found in St.

Georges Street in the late 1600s was never developed into anything, as

it could never have competed with the existing Ipswich Spa, a

sulphurated spring on St. Margarets Green.

B. St Margarets Green

A puff for 'Ipswich Spaw Waters' appeared

in the Ipswich Journal for

May 20-27, 1721; as the address was St Margarets Green, the source was

probably one of the Christchurch springs:-

‘IPSWICH SPAW WATERS

Experimentally found to be good in the gravel of the kidneys,

obstructions in the liver, spleen &c. Hectic fevers, the

scurvy,

violent vomiting, lost appetite, the jaundice, King’s-Evil, salt and

hot humours in blood, pains in stomach, frequent spitting of blood, or

bleeding at the nose, diarrhoea or blood fluxes. Sold at two

pence per

flask or quart, or each time of drinking what you will in the

morning.

By me, JONATHAN ELMER, living on St Margaret’s Green, Ipswich.’

Waters possibly from near this spring were advertised May 16-23

1724 in the Ipswich Journal ‘The

Ipswich Spaw Waters is now opened by Mrs Martha Coward, and

Attendance

will be given every Morning at the Bath on St Margaret’s Green, from 6

to 9 at One Penny per Morning, and Two Pence for each

Falk [presumably

‘Folk’] carried off.’

At the height of the Regency Spa craze, around 1814,

letters appeared in the East Anglian

Daily Times:

1) M.D. of Bury St Edmunds compares Ipswich springs to German Spa

waters and says they are better than German Spa or Tunbridge Wells if

drank at source (Georgians generally couldn’t bottle water as it went

off after 3-4 days from bacteria.)

2) H. Seekamp writes that Issac Brook, a cooper, discovered a

sunken, brick arched spring in St Georges Lane that he supposed was

mineral water as it had such a foul taste. Three Doctors

(including famous Dr Coyte) had the

water analysed and found it to be equal to the waters of Bath –

Medcalfe Russell of The Chantry had been recommended by his London

doctor to go to Bath to take the waters took this water instead and was

cured. Given the description of 'foul-tasting' waters of St Georges

Street, perhaps this second letter can be ascribed to exaggeration by

the yellow press.

C. Holywells

The reputed mineral springs with healing properties which poured

down Holywells Park was a myth created by the Cobbold brewing family.

The Cobbolds used to provide part of the town water supplies and used

the same Holywells

water from their estate as they used to brew their beer (beer-brewers

require hard water for the best beers – something resulting from the

Ipswich chalk beds); however, it

appears that this water

was plain, clean, crystal-clear, shallow spring water. Spa waters seem

to require quantities of iron (termed Chalybeate) and/or sulphur to

confer some tonic effect. It is not clear how the resultant Cobbold

beer would taste if it had been brewed from such mineral-rich water. Holywells

was not, as many believe, named after the 'Holy Well' of Holywells

Park which was frequented by pilgrims but after a 'Hollow well'. (However,

across the river, close to the Stoke area of Ipswich, there

certainly was a 'holy well', recorded as 'Haligwille' in a boundary

charter of AD 970; this spring was on a hillside at the former Fir Tree

Farm and may have been close to where the renowned hoard of golden Iron

Age torcs were discovered in 1968: Holcombe Crescent,

Belstead Brook.)

D. Dykes Alexander's estate

G.R. Clarke in his 1830 history of Ipswich (see Reading

List) mentions another spring that never froze in the

grounds of a cottage next to The Shears Pub on land belonging to

Dykes-Alexander fairly near to the other spring. Richard Dykes

Alexander’s house was at the former Bank on Barrack Corner, now

converted into flats (see our Blue Plaques

page). The water from this well was sent to London for analysis by Mr

Barry who stated that it contained iron sulphate, iron carbonate,

sulphurated hydrogen (from degrading pyrites) and he saw no reason why

this water and Ipswich spring waters with different properties could

not be rendered serviceable and bought into general use.

(The above is based

mainly on research by Adrian

Howlett.)

As we now know these enterprises did not thrive and it is, perhaps, a

tribute to Ipswich that such quackery and snake-oil seller's scams

failed in the town, where they were so profitable (but, no doubt,

ineffective) elsewhere. Cheers!

The eastern conduit

'[In 1615] the new pipeline was to be supplied from springs near

Cauldwell Hall, not far from the source of the Cauldwell Brook.

Topography and the street pattern ensured that the route of the

pipeline could hardly have been simpler. From the Cauldwell springs,

about 60ft above the level of the town centre, the pipe was laid almost

in a straight line, following the course of the Cauldwell Brook down

Spring Road and St Helen's Street (GreatWash Lane) to the junction with

Upper Orwell Street (The Wash) at Major's Corner, then along Carr

Street and Tavern Street to the Cornhill, a distanceof a little over a

mile.' (David Allen, see citation at the foot of this web page.) The

cistern in which the water was collected was housed in a lean-to

structure adjacent to the Old Town Hall (formerly St Mildred's Church)

on Cornhill with intermediate cisterns along the one mile length. An

interesting feat of water engineering. By 1848 nearly 1,500 homes were

taking this water from a couple of mains in Carr Street.

The

following excellent text by John Norman, Chair of the Ipswich Society,

formed the Ipswich Icons

column in the Ipswich Star

newspaper (16.6.2016) and it ranges from the influence of the monastic

houses on water supply to Thomas Cobbold's move to Ipswich in pursuit

of its sweet waters to brew his beer and on to the Ipswich Water Works

in, logically, today's Waterworks Street:-

"Monasteries and geology brought a fresh water first

"Ipswich was one of the first towns in the country to enjoy a piped

supply of clean fresh drinking water, initially to conduits (taps) in

the street but later directly into their homes. There were two

reasons why Ipswich was in at the beginning, firstly the monasteries had both the demand for and

the wherewithal to construct supply pipes and secondly Ipswich is

blessed with a natural water filtration system.

"The Augustinian Priory of St Peter and St Paul, founded in the late

12th century, was situated close to St

Peter's church in what is now

College Street. Residential

accommodation for dozens of monks

required a regular supply of drinking water. Traditionally the

monks would have carried it from a spring, a well or from a local

stream but here there was a natural supply oozing from Stoke Hill on

the other side of the river. A supply pipe was required.

This lead pipe started in the hillside below St Mary’s Stoke, crossed the river in

the shallows upstream of Stoke Bridge

and into the Priory. Evidence suggests it was in place by the

late fourteenth century. This supply later became a source

of water for the Stoke Waterworks Company (supplying St Peter’s parish).

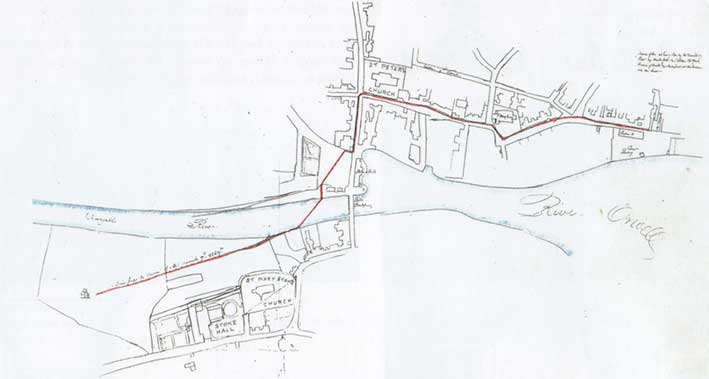

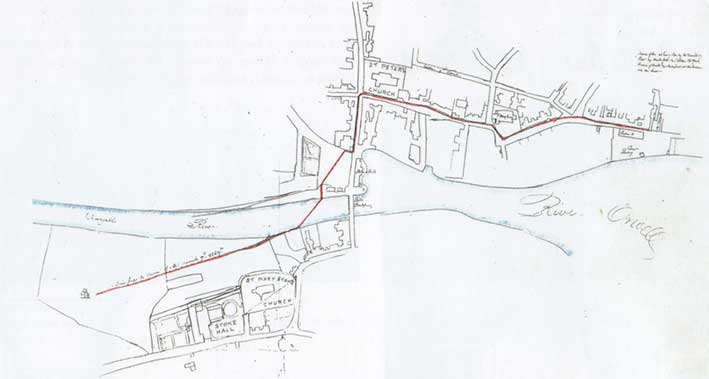

c.1795

c.1795

[Above: Isaac Johnson's sketch map of the main water pipe, shown in

red, from the water-house on land (Waterhouse Meadow) belonging to

Stoke Hall, c. 1795 – taken from Blatchly: Isaac Johnson, see Reading list. See our Stoke

Hall page for

another, more finished map of the Stoke Hall area by Johnson; you can

also read an 1819 sale notice description of the income derived from

sale of water to the town.]

"The Monks at Blackfriars almost certainly had a piped water supply

discharging into a fountain in the Garth, the garden on the middle of

the Cloisters. Evidence suggests the supply was from the

Cauldwell (Cold Well) estate on the hillside further east.

Although frowned upon by the monks it was the habit of parishioners to

tap into this pipe and insert quills (smaller pipes for their own

individual supply).

"In 1569 the Corporation acquired the buildings at Blackfriars to

establish a workhouse, a facility that became Christ’s Hospital, endorsed by

Letters Patent from Elizabeth I in 1572. Excavation at

Blackfriars have revealed that there was a feature in the Garth and it

sounds rather romantic to imagine this as a fountain, continuously

issuing fresh cold water for drinking, cooking and washing.

"There is no documentary or archaeological evidence of where the

Augustinian canons at Holy Trinity Priory (Christchurch

Mansion)

obtained their supply but there are multiple springs issuing from the

slopes of Christchurch Park. A conduit from one of these ran into

the town centre and terminated in a faucet at Conduit House on the

corner of Tavern and St Lawrence Street, (there is a plaque high up on

the building to mark the spot). [See our Ipswich Coat

of arms page for photographs of this.]

"The second reason Ipswich has an almost limitless supply of fresh

drinking water is the geology. In very simple terms Ipswich is

founded on chalk, overlaid with clay (London Crag) which, above the

sloping valley sides, is then overlaid with sand and gravel. Rain

water passes through the filtration level (the gravel) which naturally

removes detritus leaving clean water to emerge from the spring someway

down the slope. Very early on in the life of the town the water

was described as being “quite free from deposit, colourless, inodorous,

and with agreeable taste.” Thomas Cobbold had been taking

shipfuls of

Holywells water to his brewery in Harwich

(founded 1723) until he

realised that it would perhaps be more sensible to move the Cobbold

Brewery to

Ipswich (1746).

"Before the houses were built in Bolton Lane

there was a Water House

just inside the park, close to the Toll House controlling access to

Westerfield and Tuddenham Turnpike Roads. It consisted of a

single room with large tank, constantly supplied with fresh water from

an adjacent spring, the overflow from which ran down Bolton Lane and no

doubt [ended up] as the stream flowing along Upper and Lower Orwell

Street. This stream was difficult to cross in Orwell Place so

stepping stones were used and the area became the stepples or the

Wash.

"Cobbold, who had moved his brewery from

Harwich to Ipswich to be

adjacent to the wholesome water supply of Holywells sold the water to

some 600 householders, expanded this side of the business and

established an additional source of (ground) water north of St Clement's

Church in what was then Back Street (Edward White's map

1867). The

street later became Waterworks Street and the business was purchased by

the Corporation in 1892 to become the Ipswich Corporation Waterworks

(ICWW). There was debate as to whether they could also take

control of the Stoke Waterworks Company, by then owned by the Eastern

Counties Railway, which they did. In 1973 ICWW became part of

Anglian Water Authority, one of ten regional water management

companies. Anglian Water was privatised in 1989."

Waterworks

Ipswich Corporation Water Works played an important part in the public

health of Ipswich. Its story is told on our Street furniture page in relation to

cast iron 'ICWW' Hydrant covers set into the pavements. By the mid-19th

century, privately-owned reservoirs charged inhabitants for their water

supply including those owned by the Cobbolds' in Holywell, the

Alexanders' – the Quaker bankers – in St Matthew's and the Waterworks

Company in St Clement's. The town's 4,000 other

households relied on public pumps or their own wells, most of which

were contaminated. As wealthier people moved into homes on the higher

ground of the Fonnereau's northern suburb ('the big houses round the

park'), pressure increased for better supplies and money, as it so

often does (many members of the Council had moved there themselves),

talked and the Waterworks Company built a reservoir in Park Road, but

it was soon too small – see our Coat of arms

page for a feature there bearing the Borough crest. The Council bought

the company in 1892 and

hastened to review and improve water provision. Water hydrants were

placed at strategic points; it was calculated that the consequent rise

in rates would soon be recouped by householders by the lower fire

insurance premiums. By 1900 virtually every one of the town's 14,000

households had running water.

Thurleston Lane pumping station

1990

image, Courtesy

Ipswich Society

1990

image, Courtesy

Ipswich Society

The central panel above the door reads:

'ICWW

1913'

The above 1990s photograph by Tom Gondris can be found on the

Ipswich Society's Image Archive (see Links). The pumping station lies

in a dip in the surrounding land to the north of the Whitton housing

estate and close to Akenham Church – on of the most remote churches in

the county.

'Whitton Water Pumping Station, Thurleston Lane, 1913. Formerly Ipswich

Corporation Waterworks. Single storey building. Red brick with Suffolk

white brick features. Clay tile roof. Clerestory roof light. Brick

dentilled eaves. 7 window range, multi-light iron framed windows with

brick arch and keystone heads. Windows set in red brick panels with

white brick piers. Circular windows in gable ends. Panelled double

central door with arched brick head and fanlight. Stone capping to

gable ends, corbelled at eaves.' (Ipswich Borough

Council's Local list SPD – see Links)

[UPDATE 4.12.2020: 'I've

just followed the link on facebook to the section about the water

supply. I live in Anglesea Road and a lot of the old sales particulars

for the houses here state that all the pipework, cisterns and W.C.s are

the property of the Broke Hall

Waterworks and do not form part of the fixtures and fittings.

Was this usual? And would they have repossessed them if the residents

didn't pay their bills? Thanks for the website. I always land up

spending ages on it clicking on various links.' - from a browser of

this website. Thanks for this

contribution concerning a waterworks about which we had no knowledge.

The Mill River (‘the lost river’ described in its own passage further

up this web-page) which once ran from Foxgrove on Foxhall Road all the

way to the golf course near the Broke Hall housing estate and on to

join the Deben shows that water was a feature in the eastern outskirts

of the town. Any more information about the Broke Hall Waterworks and

this practice of retaining ownership of water fixtures and fitting

would be welcome.]

Sewerage and Sewage

Sewerage is the

infrastructure that conveys sewage

(human waste and waste water from a variety of sources) or surface

runoff (stormwater, meltwater, rainwater) using sewers. The words

'sewage' and 'sewer' came from Old French essouier (to drain), which came

from Latin exaquāre.

Concomitant to the improvement in water supplies was the crying

need for adequate sewage provision. It is worth recalling the

uncomfortable fact that, in the past, many households stored their

human ordure in

tanks and sold it to the Night Soil Man to be sold on to farmers for

manuring their fields. Imagine one of the tightly-built courts or yards and the fact that an average

human might produce five hundredweight of solid waste in a year; no

wonder Ipswich town was odiferous. Worse still, building sewers not

only increased the rates, but resulted in loss of income. Not just to

individuals, but to importers of London's sewage which arrived in boats

at Ipswich docks for distribution around Suffolk for improving crop

growth. Perhaps when Suffolk people run down Ipswich there is a folk

memory of a time when it was an inlet for Londoners' faeces.

For many years the open sewer was commonplace: a central gutter in a

dirt road into which residents poured the contents of their chamber

pots and much else. If they were fortunate, the gutter would be flushed

down with spring water moving towards the river. Another method of

disposal was the dunghill; the area now bordered by Upper Orwell

Street, Bond Street and Eagle Street bore the name 'Cold

Dunghill'. Cold Dunghill was a street listed in the 1851 census

enumerators' books defining an area outside the town ramparts Later,

the town's shallow and inadequate sewers once discharged into the River

Orwell at Common Quay. This outlet was moved south of the gasworks on

the east

bank when the Wet Dock was built in 1842. Peter Schuyler Bruff, the

famous railway engineer responsible for the EUR

railway tunnel through Stoke Hill, was asked to design an improved

sewage system in 1857. It was not until 1881-2 that, with

modifications,

this system was built because of the authorities baulking at the cost.

Bruff's low-level sewage system through the heart of the town

eventually reached outlet tanks and a treatment plant a mile

downstream at Hog Highland (now part of Cliff Quay) on the Greenwich

Farmland. Ironically this had been a favoured picnicking spot, visible

to those taking a Sunday stroll on the leafy Promenade on the Island. The final cost of sewer-building was

£60,000.

Here is the text of John Norman's Ipswich

Icons column in the local press (2.10.2016), reproduced by

permission:-

"Project Orwell

brought much-needed

sewerage relief to the town

This week’s article is written under a false premise. I very much doubt

if you have ever seen this ‘icon’ and you almost certainly never will,

but it is an essential bit of kit contributing quietly to the

well-being of Ipswich, writes John Norman, of The Ipswich Society.

Ipswich was late introducing public sewers and although Peter Bruff (of

Eastern Union Railway fame) was commissioned to

design a drainage

system in 1857 it wasn’t until 1882 that the low level trunk sewer was

constructed. The reference to ‘low level’ implies across the lower part

of the town centre, Bramford Road to the Wet Dock and on to Pipers Vale

(the site of the present day water treatment works).

In 1927 civil engineer Edward McLaunchan designed a modern sewage

system and treatment works (completed in 1932). A key component was the

high level sewer which ran from Norwich Road through the town centre

and then across the Suffolk College site to the new sewage works.

McLaunchan promoted a scheme with a final outlet into the Orwell that

would not leave solids on the river bed or cause offensive odour. It

proved to be a very efficient system, but it wasn’t designed for, and

couldn’t cope with, sudden surges caused by heavy downpours. In such

conditions the system simply overflowed, into the Orwell, into the

Gipping, and occasionally into the street.

By the end of the 20th Century the town’s sewers couldn’t cope in times

of heavy rain. They were perfectly adequate for the everyday sewage but

because Ipswich has a combined system (both rain water and foul

discharge into the same drain) when a major storm deposited substantial

quantities of water in a short time the sewers overflowed, and the mix

of rain water and sewage spilled into gardens and low lying areas.

In the 1990s a European Urban Wastewater Treatment Directive instructed

all water authorities to make changes to stop this happening. In

Ipswich the solution was Project Orwell, a deep level large diameter

sewer from Bramford Lane allotments along the line of Norwich Road,

Anglesea Road, under Christchurch Park and then sweeping a slow curve

to Alexandra Park and Duke Street to Toller Road.

All of the major sewers the new tunnel passed under were allowed to

overflow into it thus in times of great storm the new tunnel simply

held a vast quantity of water until the storm had passed, water that

was then pumped (usually overnight) to the treatment works.

Project Orwell started in January 1998 with a large round hole, a

vertical shaft on a site adjacent to Toller Road. A tunnel boring

machine or TBM, affectionately named Athena by the guys on site, was

lowered into the hole and slowly but surely dug her way the 5km to the

west side of town. She drilled a 2.5m diameter hole through soft chalk

some 20 metres down, pulverised the chalk with the lubricating water

and pumped the resulting slurry back along the tunnel. This was then

carted away for use as an acid neutraliser on local farmland.

Athena was followed along the bore by a railway line, an ever-

increasing length of single track which was used to deliver tunnel

linings, additional track and men to the workface. The narrow gauge

railway didn’t last long; as soon as the TBM reached its destination

the track laying process reversed and all signs of the railway were

removed leaving a smooth bore, clean-lined tunnel with nothing to

hinder the flow of water.

In addition to the tunnel six vertical shafts were constructed to act

as additional storage capacity, each has a vent about the size of a

lamp post which is the only visible sign of the vast construction

project below the surface.

Civil engineers Amec completed Project Orwell in March 2000, in total

it had cost Anglian Water £33 million but had provided relief from the

unpleasant flooding that some residents had increasingly suffered."

Evidence of Project Orwell can still be found in the town. Here is

John's photograph of a corner of Alexandra

Park near to the bend of Milner Street and Kings Avenue (with

Suffolk New College in the background). In the foreground one can see

the Project Orwell cover over the access shaft to the

tunnel; the accompanying vent pipe rises behind it.

Image courtesy

John Norman

Image courtesy

John Norman

Further

reading – David Allen: The public water supply of Ipswich before

the Municipal Corporations Act of 1835. Suffolk Institute of

Archaeology and History,

2014.

Bathing places

[should we have placed this section

somewhere other than after 'Sewage'? -Ed.]

The construction of the Wet Dock in the late 1830s also caused the

closure of the town's bathing establishments: that in St Clement's run

by John Barnard, a second (which was only a few years old and featured

hot salt water, vapour and shower baths0 next to St Mary-At-The Quay and the third in Over

Stoke, off Wherstead Road. All three were replaced by another Stoke Bathing Place run by the

Corporation. Some will recall – and many will

have heard of – this Stoke Bathing Place which was 100 yards long and

was situated close to the bottom of New Cut, today the site of a

sophisticated anti-flood barrier. It was defined by straight barriers

dividing it from the wide river basin and was refreshed by tidal

waters. Swimming here was spartan or invigorating depending on your

viewpoint. Here is an aerial view of Stoke Bathing

Place in 1930 from the remarkable Britain

From Above collection (see 'Special subject areas' in Links). Note that the Griffin Wharf branch line

curves in from bottom centre. The Stoke Bathing Place was removed in..

during the building of the West Bank container terminal.

1930

aerial view

1930

aerial view

See our St Helens Street page for a

similar aerial view of West End

Bathing Place on the Gipping at the end of Constantine Road. It

closed in 1936 due to pollution from the river.

Piper’s Vale Pools

were on the east bank of the River Orwell, they opened in 1937 close to

where the Orwell Bridge is now. It was demolished in 1979.

Fore Street Baths

, one of the earliest such public swimming pools in the country,

continues to provide bathing facilities in Ipswich, particularly for

clubs and schools.

St Matthew’s Baths closed after

Crown Pools opened in 1984. This roofed site was open for swimming in

the summer and the bath was boarded over and used as an events venue in

the winter months, playing host to many groups including a young Led

Zeppelin.

Broomhill Pool was built in

1938 at a cost of £17,000 and has been closed since 2003. A campaign

has been running since then to reopen the site.

See our Ipswich in 1912 PDF for

photographs of bathing places on pages 31-33.

Does Ipswich 'own' the River Orwell?

It would be remiss of us to ignore a sore point of the town's

governance over its river as it flows to the sea. This takes us back

into centuries of history and a continuing feud.

"More intractable was the threat to Ipswich's commerce from Harwich,

situated at the very mouth of the Orwell. In the 1270s Harwich was

receiving assistance from its lord, the earl of Norfolk, who had

blocked the river with a weir, in order to divert to Harwich ships

bound for Ipswich. (Ipswich, on the other hand, had no great lord below

the king, nor serious commercial rival, despite its competition with

Harwich for control of Orwell haven; its history is therefore

comparatively quiet.) In 1340 an inquisition concluded that the port of

Orwell (itself possibly an urbanizing settlement which ultimately

failed to preserve an independent identity), and the estuary leading to

Ipswich were within the (admiralty) jurisdiction of Ipswich, and that

it was the Ipswich authorities – not those of Harwich – who could

collect tolls at Orwell port. In 1378-79, Ipswich and Harwich were

again in contest, over a location in Orwell Haven called Polles Head,

which an inquisition decided should be considered part of the port of

Ipswich." (from the website History

of medieval Ipswich; see Links)

Rober Malster in his

book A history of Ipswich

(2000; see Reading list) summarises the

issue:-

"In 1338 and 1339 Edward III spent a considerable time at Walton Manor

assembling his fleet in the rivers Deben and Orwell for the attack on

France. Walton Manor was a handy base from which to plan and carry out

such an operation, for on one side was the Orwell anchorage and on the

other the port of Goseford, centred on the 'Goose-ford' across the

King's Fleet, a creek off the Deben, which privided a link between

Walton Castle and Falkenham and Kirton.

"It was while Edward was at Walton that he mistakenly granted

jurisdiction over the haven to the town of Harwich, provoking an

immediate appeal by the burgesses of Ipswich, who pointed out to him

that

'the whole haven of Erewell in the arme of the sea there to the said

Towne of Ipswich dothe belong, and from all times passed hathe

belonged'. If not the beginning, it was the continuation of a rivalry

between the two towns that soured relations between them for centuries.

In an attempt to convince the king of his error, the burgesses of

Ipswich averred that because of the interferance of the Harwich men

they were preventing the fee farm, the sum of money that they paid to

the Crown each year." [Edward soon revoked his grant to the 'bailiffs

and men of Herewicz'.] ...

"Nearer to home the disputes between Ipswich and Harwich rumbled on. In

1379 Ipswich petitioned Richard III that they might have the haven to

Poll Head, a point seaward of Landguard Point 'wch they have

time out of memory belonging to them', officially and clearly assigned

to the town. The 13-year-old king gave directions for an inquiry to be

held, and at an inquest held at Shotley on 3 November 1379 a dozen

witnesses declared under oath that the port of Ipswich extended

downriver to the Poll Head, 'and so hathe donne time out of minde, and

remaineth so...'

"The town of Ipswich had gained jurisdiction over this muddy river

initially as a result of King John's charter [1200]. Succeeding

monarchs confirmed the charter and extended the privileges enjoyed by

the citizens, Henry VIII more particularly stressing the maritime

nature of the town by specifically confirming the Corporation's

jurisdiction over the Orwell. He granted the Corporation admiralty

jurisdiction: 'The Bailives of the said Town, for the Time Being, shall

be our Admirals, and the Admirals of our Heirs, for and within the

whole Town, Precincts, Suburbs, Water, and Course of Water."

In December 2019, Andy Parker of the Ipswich Maritime Trust gave one of

their talks on Henry VIII and the

ownership of the Orwell. Post-1066, the Bigod family ensured

that Dunwich, between Aldeburgh and Southwold, was the main port of the

county. With the decline of Dunwich as a major port, Ipswich became

dominant culminating in the award of its charter in 1200. This

established the Ipswich Corporation – effectively its Portmen, Bailiffs

etc. (some 64 men in all) – acting to control trade on behalf of the

Crown. The docks were the economic heart of the town and the basis of

its prosperity. At its peak over 60% of the country's wool exports went

through Ipswich, with finished goods and wine from the Rhineland coming

in. The power of the town probably reached its peak in 1519 with the

grant of the Patent of Henry VIII(§). This gave the

Corporation 'jurisdiction of admiral' within the town, as mentioned

above. The town's Bailiffs and Burgesses now had the right to make and

alter ordinances governing trade. Their jusidiction was said to extend

five miles north to south and four miles east to west. The grant

included the Orwell from high water mark down to a point now marked by

a stone on the southern bank just upstream from Shotley marina. Recent

speculation has focussed on the precise location of the marker-stone on

the bank of the Orwell, or the location of 'Poll Head' (or 'Polles

Head').

(§) It is, perhaps, unlikely that Ipswich would have

benefitted in this way without the intercession of Henry's Lord

Chancellor, Thomas Wolsey. The Patent was signed at Hampton Court,

which was Wolsey's palace, not Henry's (although he seized it later).

Wolsey, of course, had considerable interest in his home town including

the planned founding of Wolsey's College.

The Shrine of Our Lady of Grace, promoted