Christ's

Hospital School & other charity schools

A

riot of colours: Grey

Coat Boys, Blue Coat Girls,

Blue Coat Boys, Redsleeve

Boys and Greensleeve Girls schools... all Ipswich charity schools (not to mention Tooley's red and blue

colours)

Christ's

Hospital Buildings, 15 Wherstead Road

Ipswich was one of the first towns to adopt a compulsory poor rate to

finance the care of the 'indigent' poor who would formerly have been

cared for by the dissolved religious houses*. In 1568 it was decided to

build a poorhouse to complement the work of the Tooley Foundation; it

was named Christ's Hospital. Attached to this was a workhouse where

'vagrants and idlers' were put by the local beadle. 'Christ's Hospital

School' was run from some of those buildings. Tireless

documenter of Ipswich history, Simon Knott (see Simon's Suffolk

Churches on our Links

page) has discovered

the grave of the headmaster for 27 years of Christ's Hospital School,

William Platt Crossley: "In 1871 and 1881 he was

living with his wife Martha and

their children in the School House, Shire Hall Yard off of Foundation

Street in the middle of Ipswich, and his occupation was given as 'head

teacher, boys day school (endowed)'. Our Foundation

Street page shows the location of the school in School Street on a

1902 map. The school itself had moved to

grand new premises on Wherstead Road in 1841, but the coming of the

railway and the rise of dockside industry led to its closure and

demolition in the early 1880s. By 1891 the Crossley family had moved to

Tavern Street where William Platt Crossley now owned and ran a

tobacconist's shop. Shire Hall Yard remains as a street name between

Foundation Street and Lower Orwell Street."

[*The Dissolution of the

Monasteries, sometimes referred to as

the Suppression of the Monasteries, was the set of administrative and

legal processes between 1536 and 1541 by which Henry VIII (reigned 1509

until his death in 1547) disbanded

Roman Catholic monasteries, priories, convents and friaries in England,

Wales and

Ireland, appropriated their income, disposed of their assets, and

provided for their former members and functions. He was given the

authority to do this in England and Wales by the Act of Supremacy,

passed by Parliament in 1534, which made him Supreme Head of the Church

in England, thus separating England from Papal authority, and by the

First Suppression Act (1536) and the Second Suppression Act (1539).

Henry's young son, Edward VI, came to the throne in 1547 and, under

Thomas Cranmer's guidance, issued Injunctions for Religious Reforms in

the same year; in 1550, an Act of Parliament was passed 'for the

abolition and putting away of divers books and images', which continued

the Dissolution and introduced iconoclasm which removed or destroyed

'idolatrous' images.]

1843

1843

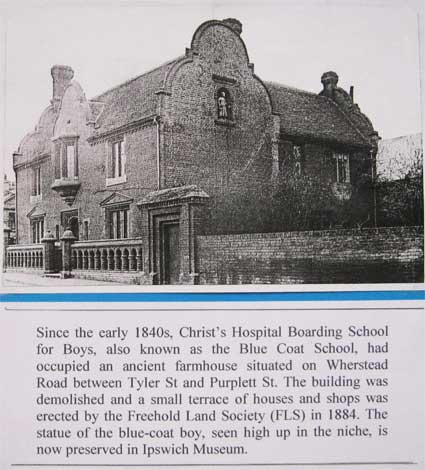

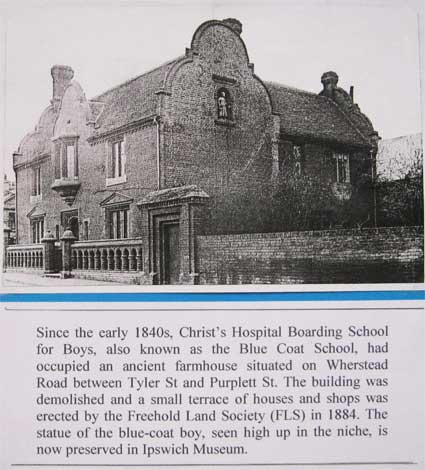

The above engraving, made by Henry Davey, is

dated 10 February 1843 and captioned: 'Christ's Hospital School,

Ipswich. Originally,

founded by charter of Queen Elizabeth, 16th May, 1572, it stood in the

Shire Hall Yard, St Mary-at-the-Quay,

and was removed to this spot in

1841 ... There is now accomodation for 40 boys who are educated,

boarded, lodged and clothed &c. from the funds of the charity.' In

August 1840 the charity trustees had appointed John Medland Clark,

designer of the 1844 Custom House, as

their architect to provide an improved Christ's Church Hospital School.

Eventually Chenery's Farmhouse in Great Whip Street was adapted for the

purpose. This despite plans drawn up by Clark to remodel the Friars'

Dormitory in Foundation Street (still used by the grammar school, but

in

poor condition) as

a new home for Christ's Hospital School.

See our 1867 map on the Felaw Street

page for the exact location

of the 'Blue Coat School' on Wherstead Road between the junctions

of today's Tyler and Purplett Streets.

2018 image

2018 image

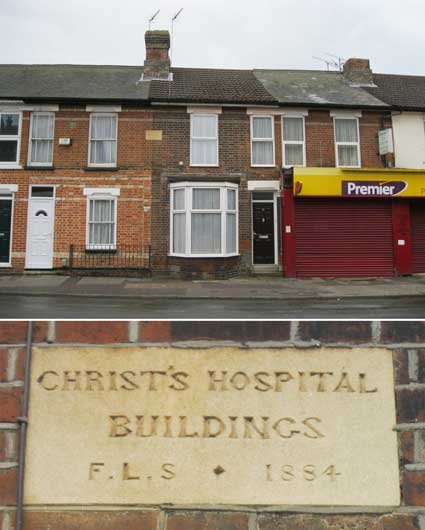

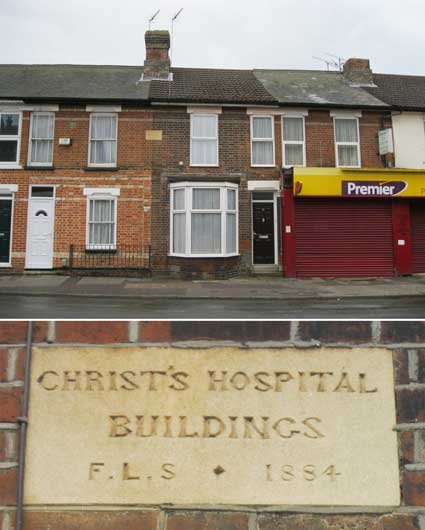

Above left: photograph

and caption by Over Stoke History Group. Above right:

the 150 year-old carved wooden figure of a Blue Coat boy which

decorated

Christ's Hospital School, as displayed in the You Are Here! The Making Of Ipswich

exhibition at the Art School Gallery in 2018.

There is indeed an 'FLS' (Ipswich &

Suffolk Freehold Land Society) plaque above numbers 13 the former

newsagent's

shop

and number 15 in

Wherstead Road which reads:

'CHRIST'S

HOSPITAL

BUILDINGS

F.L.S . 1884'

This stood near the site of

the school which was demolished in the 1880s and, given the former

Head's proprietorship of a Tavern Street tobacconist's mentioned by

Simon Knott,

perhaps the newsagent's shop

is appropriate.

2013 images

2013 images

See our Felaw Street page for

the detail of White's 1867 map showing 'The Blue Coat School'

(Christ's Hospital) on Wherstead Road between the junctions of Purplett

Street and Tyler Street; so,

definitely on the site of

the terraced houses shown here.

Ruth Serjeant's research paper on the architect John

Medland Clark:

"The earliest building in Ipswich which can with certainty be

attributed to J.M. Clark is the Christ's

Hospital School, formerly at the junction of Wherstead Road and

Purplett Street. In a competition advertised by the Ipswich Charity

Trustees (27 Jun. 1840) he won the premium of ten guineas, against two

other entries, for the adaptation of the Chenery farmhouse on the site,

and was duly elected architect for the scheme (8 Aug. 1840). On its

completion it was reported that 'the transmutation of the unsightly

structure known as Chenery's Farm ... is as creditable to his talents

as an architect, as it is an ornament to that part of the town' (11

Sept. 1841). Henry Davy's etching of 1843 shows clearly why his plans

pleased the committee by their 'strict attention to the preservation of

the style of the original building ... the introduction of a wing .. .

and single storey to the rear ... and details of the exterior ...

gleaned from some of the many fine specimens of the same style in the

neighbourhood' (S.C., 8 Aug. 1840). The stepped round gables, the high

ornate chimneys and the simple symmetrical classicism of the facade

reflect in this one building at least two of the influences on

architectural styles, which, grouped together, became known as Early

Victorian. The Jacobean and Neo-Classical (of which we see elements

here) rubbed shoulders with the Elizabethan, the Neo-Gothic, the

Picturesque and the Baroque. The styles, and their influence on

architects throughout the Victorian era, were anything but static. The

main feature of Victorian architecture was the speed with which change

took place, with several fundamentally differing styles running

concurrently. Architects were freed from the restrictions and rigidity

of the rules and concepts of the classical 18th century, and enabled to

develop the freedom of choice, not only to vary style from building to

building, but also to combine one or more styles in the same building.

The acceptance of irregularity and the unexpected as worthwhile

principles in themselves, led to the growth of that eclecticism which

is the hallmark of Victorian architecture. Moreover, not only were

architects freed from the strict classical mould, but building

materials themselves, and their combination, both in texture

differences and colours, brought an exuberance to the architectural

result irrespective of the individual style of the particular building.

'Constructional polychromy' was the term generally applied to the

combination of different materials, while 'flat polychromy' was applied

to the use of the same material in different colours."

[Source: John

Medland Clark 1813-1849 'Sometime Architect of Ipswich' by Ruth

Serjeant, The Suffolk Institute of Archaeology and History reserch

paper. Volume XXXVII, part 3 (1991)]

Christ's Hospital School (1572-1881)

Henry Tooley, merchant, died in 1551 and left the bulk of his

considerable fortune to a charitable foundation whose main purpose was

to provide almshouses for ten ex-servicemen. They were to receive

clothes (a livery incorporating Tooley’s

red and blue colours), firewood and medical care together with

sixpence a week (more for those who couldn’t work), provided that they

attended morning and evening service at St

Mary-at-the-Quay. After disputes over the will delayed things for

eleven years, five almshouses were eventually built, each house either

to accommodate a married couple or two men sharing. They were probably

in the half acre orchard off Star Lane – then a much shorter, narrower

thoroughfare than today – which Tooley and his wife had leased from the

Blackfriars (dissolved by Henry III in 1538) in the 1530s. In order to

deal with rising poverty, the town acquired the Blackfriars premises

and set up Christ’s Hospital in the southern portion of its ample

buildings, the friars’ church having been demolished soon after

dissolution so that building materials and furnishings could be used

elsewhere. This is the church whose ruins are today still visible

between Lower Orwell Street and Foundation Street: the only visible

remnants of the five monastic establishments

in the town today.

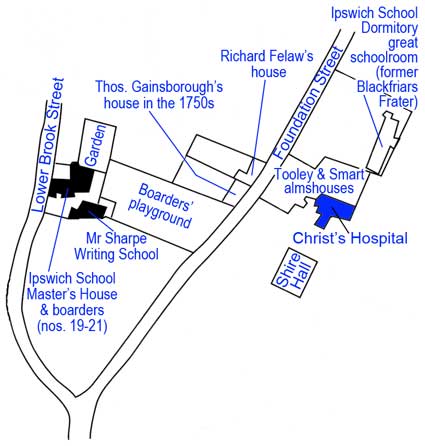

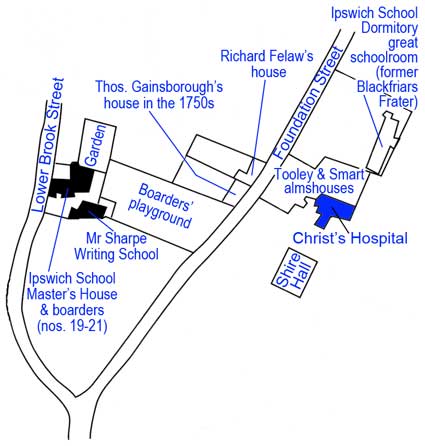

Early to

mid-19th century sketch map

Early to

mid-19th century sketch map

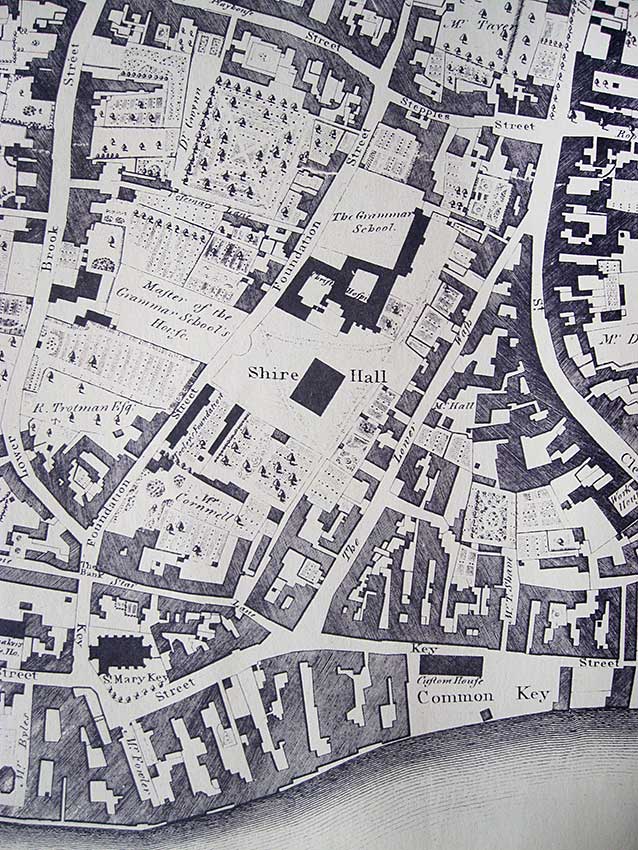

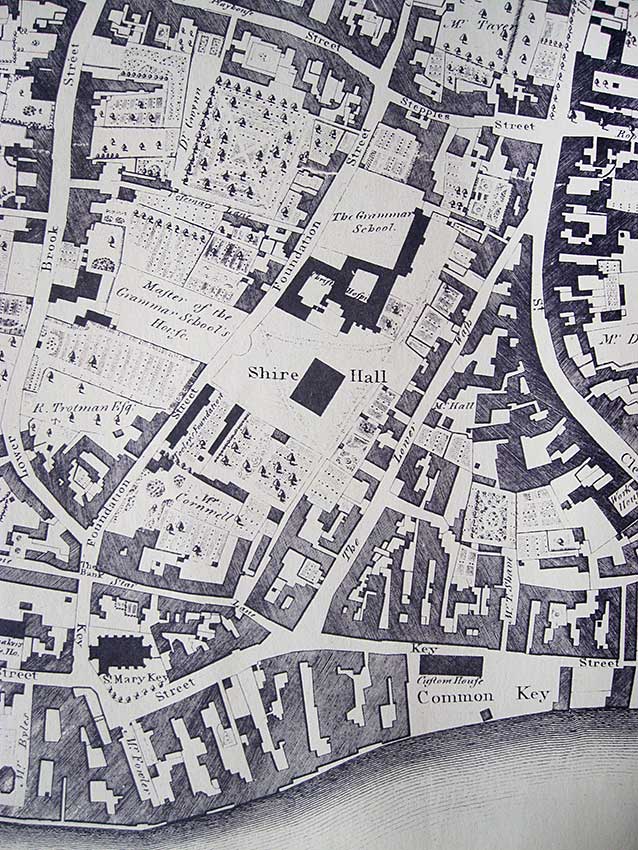

Below is the detail from Pennington's 1778 map

of this area, showing the school features. Note, just visible, the

legend 'Christ's Hospital' across the Tooley Almshouses. A row of

houses further down Foundation Street is labelled 'Tooley Foundation'

(just below the word 'Street').

1778 map

1778 map

The name ‘Christ’s Hospital’ can be confusing, doubly so in that the

nearby Richard Felaw’s house and the Blackfriars Frater across

Foundation Street were occupied subsequently by the educational

establishment which was to become The Ipswich School (sometimes called

Ipswich Grammar School among other things). The above sketch map shows

the layout between Lower Brook Street and Foundation Street which had

slowly developed since the sixteenth century and led eventually to the

move of Ipswich School to the new Christopher Fleury-designed buildings

Henley Road in 1852 (see our Plaques page

for a photograph). “Hospital”: during

the Middle Ages hospitals served different functions to modern

institutions, being almshouses for the poor, hostels for pilgrims, or

hospital schools. The word hospital comes from the Latin hospes,

signifying a stranger or foreigner, hence a guest. Another noun derived

from this, hospitium, came to signify hospitality, that is the relation

between guest and shelterer. The Latin word then came to mean a

guest-chamber, guest's lodging, an inn. Hospes is thus the root for the

English words host (where the p was dropped for convenience of

pronunciation) hospitality, hospice, hostel and hotel. “Christ’s”: it

was not Christian, as such.

Christ’s Hospital in Ipswich has been described more as a workhouse for forty inmates,

both deserving and undeserving poor, both sexes and all ages. It was

also described as a ‘seminary of thieves’; vagrants were rounded up and

sent there as a punishment. Within a generation children predominated.

This was all funded by a poor rate of £170 per year, a penny or

tuppence a week from most of the 312 taxable householders; the richest,

Edmund Withypoll (at Christchurch Mansion) paid 16 pence. Half of this

amount went to Christ’s Hospital and half to ‘outdoor relief’ to, in

the 1570s, around eighty impoverished families in their own homes.

Oddly, actors, witches and rabbit-skin salesmen were specifically

excepted from this outdoor relief. By 1597 there were nearly twice as

many on such relief and extra funds were made available by Tooley’s

trustees who were also town officials.

An incomplete census of the poor for 1597 mentions 400 men, women and

children from nine parishes, 80% being in St Matthew’s and St Clement’s

in the suburbs and St Nicholas’ is in the town. The actual total,

including the three unrecorded parishes plus Christ’s Hospital and

Tooley’s and Daundy’s almshouses (the latter founded by Edmund Daundy

on Lady Lane) would have been nearer 600

this is comparable to the figure in 1297 at the time of the wedding of

Edward I’s daughter Princess Elizabeth (see King

Street) when, despite the many

intervening plagues, the population as a whole is likely to have been

smaller. By 1600 Christ’s Hospital and the almshouses of the Tooley

Foundation, though separately managed and set up with rather different

intentions, were moving towards an ever-closer union. The road running

beside the Blackfriars western wall soon acquired its present name of

Foundation Street.

Christ’s Hospital, some time after

the last of the Elizabethan Poor Laws in 1601, gave up its role as

the municipal workhouse and eventually became a school. The will made in 1670 by Nicholas Phillips, portman,

enabled the foundation of the school in Christ's Hospital, adding

education to the other provisions of Tooley’s and Smart’s Foundation, a

century after the 1572 Letters Patent had by implication required it.

It was not a grammar school because the blue coat boys there were never

more than about twenty in number, and at fourteen, they were usually

sent to sea as apprentices.

“[Grammar school headmaster] Leman’s troubles

began

when, in September 1605, the corporation ruled that Felaw’s house and

endowments were no longer to be used for the grammar school as had

surely been that benefactor’s intention. In fact, some of Felaw’s

endowments had been diverted since the re-foundation of the school

after Wolsey's College

failed. Ever since the charitable Christ's Hospital had been

established in 1572, it had been on the collective conscience of the

borough hierarchy that provision had still to be made there for

educating poor boys. Revising their view of Felaw’s intentions

retrospectively, the corporation would found a charity school, without

dipping into town finances or their own pockets. Grammar school places

were free to the sons of the town’s burgesses who entered as foundation

scholars, but that was not something which needed to be changed. Leman

was to leave Felaw’s House as soon as possible, finding another place

in which to teach his grammar pupils. Leman naturally protested but his

chances of winning the argument were doomed when a new and powerful

town preacher [Samuel Ward] was appointed at All Saints-tide (1

November) 1605.”

Apart from Christ’s Hospital, there were three other charity schools in

Ipswich at the beginning of the 18th century, all modestly endowed: the

Redsleeve School for boys at its Master’s house in Silent Street, and

the boys’ Grey Coat School

with its sister foundation the girls’ Blue

Coat School nearby. See Curriers Lane

for a plaque which once celebrated these schools. (Confusingly,

Christ’s Hospital pupils were known as Blue

Coat Boys.) In 1818 the three had a total of 156 children

between them. As at Christ’s Hospital, they were prepared for

apprenticeship, being taught practical skills in the morning with

reading – and sometimes writing – in the afternoon. Some of the boys

were apprenticed back to their fathers so they, at least, came from

reasonably prosperous homes. Subscribers supplemented the schools’

endowment income and £1 a year bought the right to nominate one pupil.

“Lists of those voting for each candidate in this hotly

contested [Ipswich School] mastership election were recorded by that

assiduous recorder

of Borough events Devereux Edgar, in his commonplace book. Edgar was a

prime mover in establishing another charity school in 1709 with high

church and Tory support based on the Tower Church: Grey Coat Boys and

Blue Coat Girls. Boys in blue coats belonging to Christ's Hospital

school. The low church Whig equivalent based on St Lawrence followed

eventually, for Redsleeve Boys

and Greensleeve Girls.

Supporters of the two schools insisted on the correct colours being

worn in the town so that they could judge behaviour.”

The newly-formed Charity Commissioners' new scheme for administration

of schools in 1881 meant that all the old borough charities were

combined and shared out between Ipswich School and the newly-formed

Northgate Middle Schools for boys and girls. When the Endowed School

governors were given control of the grammar

school and Christ’s Hospital in 1881 they therefore took over the

town’s

various educational charities which they amalgamated into 12 parts: 3

parts for a new girls’ secondary school, 4 for a new boys’ secondary

school and 5 for the grammar school. Christ’s Hospital was closed down after 300 years of

existence. (This would fit in with the F.L.S.

naming of the above building in 1884.) The girls got its junior school

in the southern half of the Blackfriars complex, and the boys its

larger house in the Wherstead Road, on the site of the old St Leonard’s

leper hospital. Soon both were moved to more modern accommodation.

[Sources: Bishop,

Peter: The history of Ipswich

and quotations from Blatchly, John: A

Famous Antient Seed-plot of Learning: A History of Ipswich School

(see Reading list)]

pre-1843

pre-1843

The upper cloisters, Christ’s Hospital (demolished

in 1843). The cloisters ran, with the exception of a

small space occupied by the cells of the Bridewell, along the four

sides of a grassy quadrangle and the upper galleries ran directly above

the lower ones for the same distance.

pre-1843

pre-1843

Christ’s Hospital (demolished

in 1843).

The Hospital once occupied a site at Shire Hall Yard in Foundation

Street and was founded by the Ipswich Corporation in the days of

Elizabeth I. Note the figure of the Blue Coat Boy in the niche at first

floor level. We wonder if that figure was carried across to the new

buildings in Wherstead Road (see the wooden figure above).

These engravings are from Frederick Russel

and Wat Hargreen's Picturesque

Antiquities of Ipswich (published in Ipswich, 1845).

[UPDATE

6.6.2020:

Nicholas Raphael got in touch from Sydney, Australia to say that his

third great

uncle – Alderman Abraham Raphael Jr attended the

Christ's Hospital School some time during the 1860s. For

Nic's full message, see our Old Jewish

Cemetery page.]

Charity schools in Ipswich

'In Ipswich the original benefactors were Tudor merchants Richard

Felaw, William Smart and Henry Tooley. Richard Felaw bestowed in his

will of 1482 his house ‘to be forever a common school house, or

dwelling house for the school master, together with other property, the

income from which would provide for the maintenance, not only of the

buildings but also of the running costs of the school’. Other notable

benefactors include William Smart, who with ‘The Great

Tooley of Ipswich’ (he must have been rich to gain a title

like that) left a legacy to create almshouses in Foundation Street (as

well as leaving money for the benefit of the grammar school). In the

17th Century Richard Martin left money for scholarships and William Tyler

left a similar legacy for the teaching and apprenticing of poor

children in the town.

In the 16th Century and the 17th Century there were very few schools.

The rich would pay a tutor to educate their sons, some would teach more

than one child and to these groups were added children of the poor,

supported by the benefactors like William Smart. By the 18th Century

these schools had become charitable institutions taking substantial

numbers of young children (but by no means all). They were not

universal, they taught to their own syllabus and were supported by

voluntary contributions, subscriptions and endowments. In Ipswich a

couple of these schools still exist, for example St Margaret’s was

originally the Red Sleeve School.

The Blue Coat Boy [public house] in the Old

Cattle Market was the site of the Blue

Coat School. The Grammar School had been established perhaps as

early as 1399 (by the end of the 15th Century there is hard evidence of

its existence). Its charter was obtained from Henry VIII and renewed

and improved by a further charter from Queen Elizabeth I.

When the Industrial Revolution took hold, the Wet Dock was enclosed (1844),

the

railway arrived (1846) and the urban population swelled. The

corporation began

to take a more significant role in educating the young but it wasn’t

until 1870 that compulsory education became universal, paid for by

collective taxation. The endowments which had been accumulating were

collected together and administered by the burghers of the town, 21

trustees appointed to supervise the collected municipal charities. By

1881 arrangements were in place to ensure that charitable contributions

supplemented, rather than replaced, public funding of state education.

Thus the Northgate Foundation was established, it has been through

numerous modifications and adjustments but its principles remain.

Changes at the turn of the 20th Century led to the acquisition of

school premises, the Girls’ School in School Street and the Boys’

School in Bolton Lane (see our More schools

page). School Street was alongside the Unicorn

brewery off Foundation Street, this school had previously been the

Boys’ School and before that Christ’s Hospital which at one stage was

also a beneficiary of the foundation. The site of the Girls’ School is

now the ruins of Blackfriars Monastery, a scheduled ancient monument

the foundations of which are preserved for the benefit of the town. The

Boys’ School eventually became the Music School [in Bolton Lane] and for a short time

the [public] library before being sold for conversion into apartments

Devereaux Court]. It is the

money raised from the sale of this property which provides the core

endowment for the foundation today.'

[Taken from John Norman's Ipswich

Icons column, Ipswich Star, 25 July

2016.]

Related pages:

For more on Wolsey and his ill-fated college (which, for about

two years, was also Ipswich Grammar school) see our Wolsey's College page.

Tooley's and Smart's Almshouses,

Ipswich Workhouses.

Home

Please email any comments

and contributions by clicking here.

Search Ipswich

Historic Lettering

©2004 Copyright

throughout the Ipswich

Historic Lettering site: Borin Van Loon

No reproduction of text or images without

express

written permission

1843

1843

2018 image

2018 image 2013 images

2013 images Early to

mid-19th century sketch map

Early to

mid-19th century sketch map 1778 map

1778 map pre-1843

pre-1843 pre-1843

pre-1843