Ipswich Union Workhouse

Photos courtesy Steve Girling

Photos courtesy Steve Girling

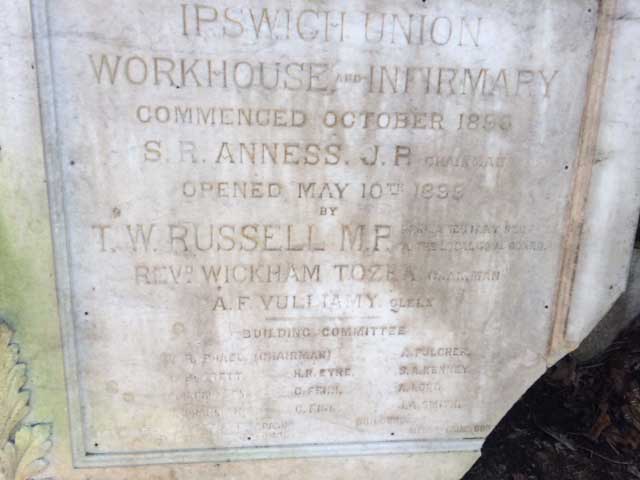

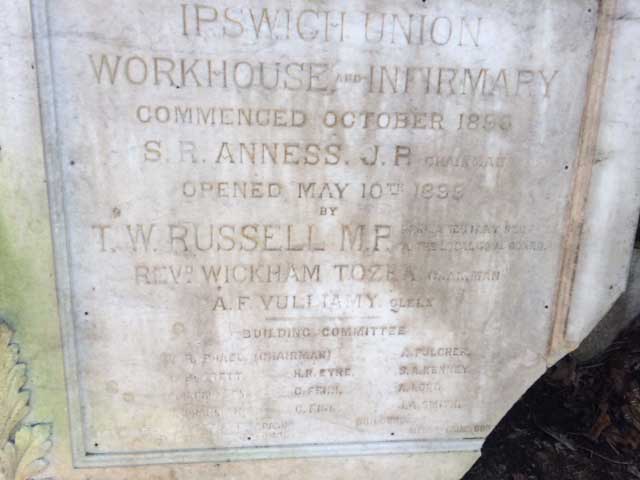

‘Hi. Thought these might be of interest to your website, this

tablet is at the Heath Rd Hospital site in a yard with no public access

so many people may not know that it exists. Regards, Steve Girling’

Many thanks to Steve for unearthing this lost fragment of Ipswich

history. The decorative carved tablet reads (some characters

speculative):

‘IPSWICH UNION

WORKHOUSE AND INFIRMARY

COMMENCED OCTOBER 1898

S.R. ANNESS. J.P.

CHAIRMAN

OPENED MAY 1O

TH 1899

BY

T.W. RUSSELL M.P.

PARLIAMENTARY SECY.

OF THE LOCAL GOVT. BOARD

REV

D. WICKHAM TOZER.

CHAIRMAN

A.F. VULLIAMY.

CLERK

———

BUILDING COMMITTEE

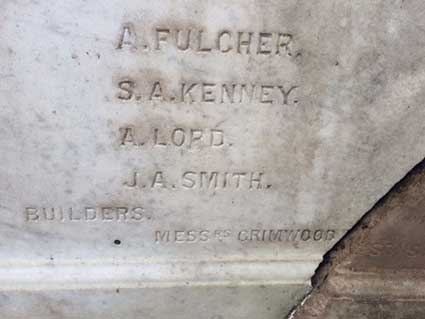

A. RAPHAEL. (CHAIRMAN) A. FULCHER. C.

BORRETT. H.R. EYRE. S.A. KENNEY. R.H.

CAUTLEY. C. FENN. A. LORD. H.

CHAPMAN. C. FISK. J.A. SMITH.

ARCHITECTS. MESSRS.

SALTER & ADAMS. & MR. H.

LISTER

NEWCOMBE.

BUILDERS. MESSRS. G. GRIMWOOD &

SONS.’

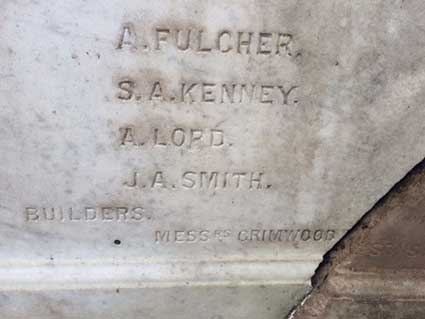

Below: close-ups with broken corner of the tablet (discoloured)

showing smaller lettering.

Note the reappearance of the name of the Chairman, Reverend

Wickham Tozer, who appears on the list of local worthies connected to Rosehill Library, which see for a

note on Tozer's role the Akenham Burial Case.

[UPDATE 6.6.2020:

Nicholas Raphael got in touch from Sydney, Australia to say that the

Chairman of the Building Commiittee listed here is his third great

uncle – Alderman Abraham Raphael Jr. For Nic's full

message, see our Old Jewish Cemetery

page.]

Ipswich workhouses

They began their existence in the county in the second half of

the 16th century. The workhouse within Christ's Hospital in Ipswich was

at the very forefront of this new method of providing assistance to the

poor and needy of society:-

Christ's Hospital (Borough

Workhouse): 1572-c.1600 (30 places).

A parliamentary report of 1777 listed a

dozen parish workhouses in operation in Ipswich: St Clement

(with accommodation for up to 70 inmates), St Helen (10), St Lawrence

(25), St Margaret (100), St Mary at Elms (10), St Mary at the Key (25),

St Mary Stoke (30), St Mary Tower (30), St Matthew (30), St Nicholas

(20), St Peter (28), and St Stephen (24).

Great Whip Street (Union

Workhouse, alias The Spike): 1837-1899 (400 spaces);

(moved to Heathfields Poor Law

Institution):

1899-1930 (400 spaces).

Background

In England and Wales a workhouse, colloquially known as a

'Spike', was a place where those unable to support themselves were

offered accommodation and employment. The earliest known use of the

term dates from 1631.

The origins of the workhouse can be traced to the Poor Law Act of 1388,

which attempted to address the labour shortages following the Black

Death in England by restricting the movement of labourers, and

ultimately led to the state becoming responsible for the support of the

poor. But mass unemployment following the end of the Napoleonic Wars in

1815, the introduction of new technology to replace agricultural

workers in particular, and a series of bad harvests, meant that by the

early 1830s the established system of poor relief was proving to be

unsustainable. The New Poor Law of 1834 attempted to reverse the

economic trend by discouraging the provision of relief to anyone who

refused to enter a workhouse. Some Poor Law authorities hoped to run

workhouses at a profit by utilising the free labour of their inmates,

who generally lacked the skills or motivation to compete in the open

market. Most were employed on tasks such as breaking stones, crushing

bones to produce fertiliser, or picking oakum using a large metal nail

known as a spike, perhaps the origin of the workhouse's nickname.

Life in a workhouse was intended to be harsh, to deter the able-bodied

poor and to ensure that only the truly destitute would apply. But in

areas such as the provision of free medical care and education for

children, neither of which was available to the poor in England living

outside workhouses until the early 20th century, workhouse inmates were

advantaged over the general population, a dilemma that the Poor Law

authorities never managed to reconcile.

As the 19th century wore on, workhouses increasingly became refuges for

the elderly, infirm and sick rather than the able-bodied poor, and in

1929 legislation was passed to allow local authorities to take over

workhouse infirmaries as municipal hospitals. Although workhouses were

formally abolished by the same legislation in 1930, many continued

under their new appellation of Public Assistance Institutions under the

control of local authorities. It was not until the National Assistance

Act of 1948 that the last vestiges of the Poor Law disappeared, and

with them the workhouses.

Up to 1834,

the

story can

be traced on our Tooley's and Smart's Almshouses

page and our Christ's Hospital

School page.

Piecemeal provision of poor houses in each parish were largely funded

from bequests from the estates of wealthy citizens.

The Old Poor Law

By the Poor Law Act of 1601, the parish was made the unit responsible

for the care and employment of the poor. Every household and land

occupier was rated (rather like Council Charge) and the money paid into

a parish fund. Two villagers, usually farmers or tradesmen, were

elected each Easter, as Overseers, to administer the Poor Law, the

parish fund and the needs of the poor. The Act classified the poor into

three groups:-

1. the helpless, who through age, infirmity, short-term illness,

accident or personal crisis, were unable to work or fend for

themselves; these had to be cared for by the parish.

2. the able-bodied but unemployed; these had to be found work, so they

could provide for their families.

3. those who could, but would not work ; these were to be punished in

Houses of Correction. See our Woodbridge

page for a surviving ‘Correction’ sign.

In practice most parishes provided for the helpless and able-bodied

unemployed, by means of out-relief: the giving of money, food, fuel,

clothing and medical care in their own homes. A minority of parishes

placed their helpless in a ‘poor house’, rather like today’s concept of

sheltered accommodation. By 1776 less than 20% of Suffolk parishes had

a workhouse, in which the poor were maintained in exchange for work,

usually spinning and weaving. An inventory of Assington workhouse in

1808 shows that the 23 paupers were provided with 18 spinning wheels,

two reels and a loom to work on. At Long Melford, in 1802, the 29

paupers were employed in wool combing and spinning. During that year

they produced 644lbs of combed wool ready for spinning and 84lb of spun

yarn.

House of Industry

Many towns starting with Bristol in 1696, set up a single large

workhouse to accommodate the poor from all the parishes within the town

boundary. Sudbury, in Suffolk, united its three parishes in 1702 and

Bury St Edmunds its two in 1747. Rural parishes, in the east and

southeast of Suffolk, adopted the same idea and based on the ancient

Hundred areas, closed all the poor and workhouses and built a large

central House of Industry. The aim was to reduce the cost to the

ratepayers, by cutting down administrative charges. Between 1757 and

1781, nine Houses of Industry, covering nearly 50% of parishes, had

been built in Suffolk. A survey of these Houses was made by

Thomas Ruggles and published by Arthur Young in 1794. The poor were

employed in all the Houses to comb and spin wool for Norwich clothiers.

Four of the nine Houses also spun hemp into linen, used to make

pauper’s clothing. In addition, at Oulton, near the coast at Lowestoft,

they made nets for the herring fishery; at Bulcamp, shoes and stockings

and at Nacton, ropes, sacks and plough lines were produced.

The New Poor Law

The dual system of parish workhouses and Houses of Industry ended in

1834. Population increases, rising unemployment in rural areas and

economic depression, following the Napoleonic wars, had led to a

massive increase in expenditure on the poor. Edwin Chadwick was

appointed, by the Government, to devise a more effective, national

system of maintaining the poor. His solution, based on the earlier

ideas of Jeremy Bentham and evidence from the Suffolk Houses of

Industry, was that the 15,000 parishes of England and Wales should be

formed into 600 Union districts, each with a central workhouse. Thus

the New Poor Law was partly based on the earlier Suffolk system. The

New Poor Law was the first instance of a nationwide organisation, being

controlled by central government. The Poor Law Commissioners and Board

laid down uniform rules and regulations, which were applied to every

pauper in every workhouse in England and Wales.

The never-realised aim was to end out-relief and make all paupers go

into the workhouse. Daily life was intended to be monotonous; the food

to be just below the quality of that available to the poorest family

who kept themselves out of the workhouse; the work tedious and

repetitive and often pointless. Even though the new workhouses were

often of the same design as prisons and seen as such by the inmates,

anyone could leave if they wanted to. But if they had no employment

there was little choice between starvation and the workhouse.

Pre-Union Workhouses

In Ipswich relief of the poor was reorganised in 1835 to comply with

the previous year’s New Poor Law. Three Relieving Officers replaced the

parochial overseers and most of the old poor houses were shut. The

inmates at this time totalled 176; these were divided between the three

largest poor houses: St Margaret’s for women and girls, St Clement’s

for men and boys and St Mary-Le-Tower for the aged and infirm. It is

worth noting that slums were a Victorian phenomenon; the word first

appears in an 1812 dictionary. Unemployment in rural areas led to mass

migration to the towns to seek work. This in turn led to a huge demand

for accommodation – something which became increasingly profitable for

those who owned land and any sort of buildings. Overcrowded,

poorly-built housing with insanitary conditions and lack of hygiene led

swiftly to high mortality rates, particularly amongst the infants. Drunkenness

and lawlessness accompanied the selling, churning

populations of the slums. The main focus of slum dwelling in Ipswich

was the Parish of St Clement which included ‘The Potteries’ and streets

running south from St Helens Street down to the river, as mentioned in

our page on Courts & yards. By the

1830s the problem of slum-living became an issue which could not be

ignored by the authorities. However, much of the early moves to

alleviate the problem stemmed from philanthropists.

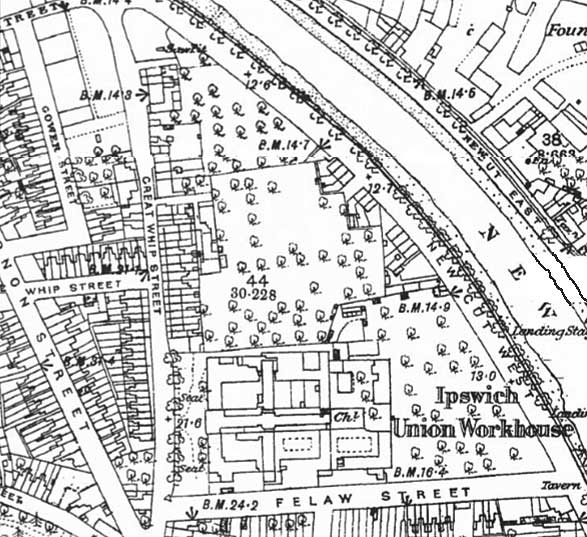

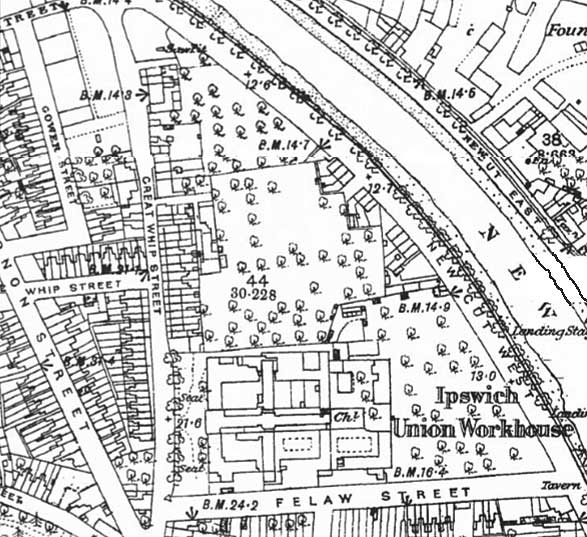

Great Whip Street Workhouse

('New Union Workhouse' or St Peter's Workhouse)

In England and Wales a workhouse, colloquially known as

a

'Spike'. This may have been due to the use of a metal nail

or spike to tease out rope fibres. The new, purpose-built Union

Workhouse was built between Great Whip Street and the Orwell in 1837

with a capacity for 400 people. Everyone from the other three houses

were transferred there. Townsmen usually located institutions which

dealt with ‘undesirables’ away from the town centre, so perhaps Over

Stoke was seen as a suitably remote place to deal with the destitute. The

Great Whip Street workhouse location and layout are

shown on the 1848 and 1867 maps on our Felaw

Street page.

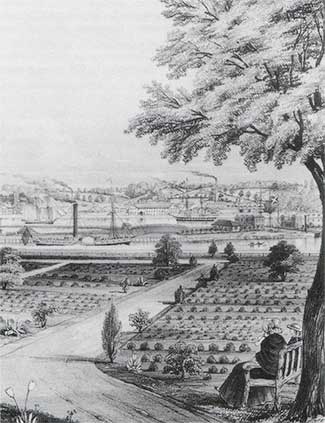

The ghostly image of the workhouse appears in the background of a

pre-1883

photograph of St Peter's Vicarage on our Bridgeward

Club page.

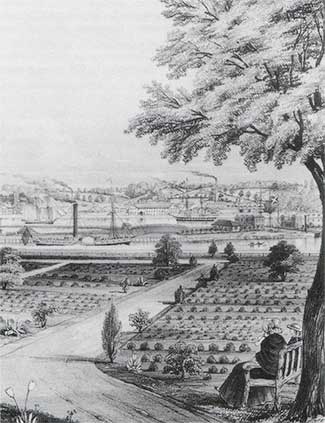

It is also shown in the background of Davy's illustration of the laying

of the Wet Dock lock foundation stone, 1839.

Above: An engraving of apparently idyllic orchards

and gardens of the Great Whip Street Workhouse can be seen as

propaganda. In the distance a paddle steamer and other shipping can be

seen on the Orwell.

The men – as in most of the rest of Suffolk – were set to pick

oakum;

this is is a the tedious process of unraveling set lengths of

tarred ship’s ropes into fibres to be used in shipbuilding for caulking

or packing the joints of timbers. Other work included making rush

matting, pumping water, or grinding corn, by hand crank wheels or by a

tread-wheel (a device common in prisons), gardening and farming the

workhouse land to grow wheat, oats and potatoes. During a 14 hour

workhouse day, between 6am and 8pm, the able-bodied paupers spent 10

hours, from 7am to 12pm and 1pm to 6pm, at work. The boys were

set to mend shoes and the women and girls to knit. Nobody was now paid

for their work.

Oakum pickers

Oakum pickers

Women were also given domestic work to do, including scrubbing floors,

forms and tables with cold water and soda. They also laundered clothes,

looked after the infants and helped to nurse the sick. Vagrants, or

tramps, known as Casual Paupers, would be given a night’s shelter in

exchange for work the next morning. For men, this was picking 1lb of

oakum and for women, 3 hours washing, scrubbing and cleaning.

Although designed mainly to provide work for the able-bodied poor, by

the end of the 19th Century the workhouse had become a combination of

hospital, lunatic asylum, old people’s home and school. Costs

were cut as demand for relief rose. Life within the workhouse was

almost unremittingly bleak, yet some lived their whole lives within its

confines. An engraving of apparently idyllic orchards

and gardens of the Great Whip Street Workhouse can be seen as

propaganda.

"The paupers on their first

admission will have a comfortable apartment..."

An insight into conditions in 'St Peter's Workhouse' can be

gleaned from this report in the East

Anglian Daily Times, 26 November 1880 sent to us by Lisa Smith,

to whom our thanks:-

"IMPORTANT ALTERATIONS AT ST. PETER’S

WORKHOUSE, IPSWICH

For a long time the question of cooking at the Workhouse has been one

of the most difficult subjects with which our Board of Guardians have

had to deal. It has been such a constant source of complaint and

expense that at last the Board decided “take the bull by the horns,”

abolish the whole of the old troublesome apparatus, and in its place

have a perfect system of steam cooking. To carry this out, a committee

was appointed, consisting of Mr. F. Turner, Mr. W. Flake, and Mr. H.M.

Elton. After going carefully into the whole thing, these gentlemen came

to the conclusion that, properly carried out, the use of tea, would not

only effect a great saving in the coal bill for cooking purposes, but

that if the system were extended to the baths and wash-houses, economy

would result to such an extent that the first outlay of the apparatus

would be quickly covered. The committee favoured the system of Messrs.

Barford & Perkins, and the Board adopting the report, the work has

been satisfactorily done by that firm.

Though Messrs. Barford & Perkins’s system involves the introduction

of an apparently complex service of pipes, it is in reality simplicity

itself. A large boiler is fixed in any part of the building, and from

this steam is conveyed to the most remote corner. At the Ipswich

Workhouse an old outhouse near the kitchen has been converted into the

engine-room, and here is now fixes a three-horse-power vertical boiler

or steam generator fitted with self-feeding apparatus. From this a pipe

is led into the kitchen, and connected with a cooking apparatus,

comprising a steam closet and three coppers, two of 60 gallons each,

and one of 40 gallons. Of the two larger of these one is used for soup,

and the other for tea, whilst the smaller is devoted to the concoction

of gruel.

The steam chest is provided with four trays, and is capable of cooking

puddings, meat, potatoes, fish, or anything the fancy of an individual,

or the rules of an institution such as a Workhouse, may dictate, for a

party of 500. At the top is a jointed pipe for supplying each of the

coppers with water, and at the back is an indicator,so that the cook is

able to tell whether the stoker is attending to his duties properly. At

present the waste steam from the cooking apparatus passes out into the

sewer, but is to be utilised for the purpose of warming the dining

hall. The apparatus does away with three coppers and furnaces. Pipes

also pass on to the old boiling room and provide hot and cold water at

all times for the scullery requirements.

So much for the cooking at the House, but the greatest and most

important alterations are those with reference to the baths and

lavatories. The old bath-rooms were dark and damp places, brick

floored, and fitted with large blue slate tanks placed close up to the

wall. In the case of the old men, the bath-room and the dormitories

were at opposite ends of the buildings, and the inmates had to march

through cold draughty passages not only to get to the baths, but also

on their return from immersion in hot water. In the infirmary the sick

had to cross the yard to go to their bath-room, which was a lean-to

shed used as a scullery, in which a slate tank had been put. This bath

has for some years been one of the causes of complaint of the

Government Inspector. The sides of the baths were also high and narrow,

so that the old folks could with difficulty get in, and more than once

one of these unfortunate people has had a fall in the attempt, and

sustained severe bruises.

Primitive as these were, there were only three in the house for the

men, and two for the women. Now eleven rooms have been fitted up with

baths, including a separate one which has been termed the “itch ward,”

an addition which the officers fully appreciate. These baths are all of

red concrete, cased in wood at the sides and tops, and are fitted with

hot and cold water and waste taps. These are both cheap and

substantial, and have also the further advantage of cleanly appearance,

which is more than can be said of the old slate tanks. The floors of

the bath-rooms are also boarded, and those attached to the sick wards

furnished with a fire-place. On either side of the house there is also

a large tank, that on the men’s side holding 100 gallons, and that on

the female side 150. These are made on the jacketed principle, that is

to say with a space between the pan holding the water and the side of

the tank. The cisterns are fitted with self-feeding apparatus, and so

fill themselves with cold water.The steam from the boiler already

described circulates in this space, and heats the water to boiling

pitch in a very short time. Pipes lead from these tanks, and convey the

hot water to the various parts of the building for the baths and

lavatories.

The laundry is likewise included in the reform. The three old coppers

have been turned out of doors, and their places taken by boiling parson

the same style as the jacketed tanks just mentioned. The eleven washing

pans round the sides of the place are retained, but each will be fitted

with a cold water tap. From these taps they will be filled, and the

steam turned on to each separately, and in five minutes boiling water

is ready for the washerwoman’s hands.In one tank the soap is

dissolved by steam, in the same manner. If properly managed,

these alterations will effect a saving in this part of the house alone

of from 20 to 25 per cent. The steam from the boiling pans is carried

round the walls to the drying room. Here, that which is condemned is

taken away, whilst that still of use is carried on to the drying

closet, and utilised for drying the linen.

The work thus done by this one generator and furnace was formerly

carried on at immense labour and in anything but a satisfactory manner

by 14 large coppers, each heated by a separate furnace. This furnaces

consumed about five tons of coal a week. The new boiler only consumes

about two tons of steam coal, a saving on that item alone of three tons

of coal a week. The laundry, which is supplied by steam in this manner,

is about 300 yards from the generator, and in all about a mile of

piping is used in the building. It should also be mentioned that high

pressure is not necessary to carry on the work. We saw the cooking

apparatus, and the hot-water tanks going with only a pressure of

between two and three pounds of steam. The contract for the apparatus

and fixing £337, and it is estimated that this outlay will be entirely

covered by the first two years’ saving.

All the work has been carried out, under the superintendence of the

Committee, Mr. Eyton taking the most active share, by Mr. Eley, the

representative of Messrs. Barford and Perkins, who is also engaged in

fixing a similar boiler at St. John’s Home. At this institution,

however, the full system has not yet been adopted, though we venture to

think this can only be a matter of time, as the advantages are so

patent that the Guardians cannot long hold their hands. We might also

mention that Messrs. Barford and Perkins’s apparatus has been adopted

at the Bury St. Edmund’s Workhouse, and at Depwade, Pulham Market. For

large establishments no more economical system can be found, and we

would commend it to the attention of all who have the management of

workhouses, asylums, or places of like character.

But the improvements at the Workhouse do not end with these new bath

rooms etc. A thorough system of earth closets has been fixed in the

room of the abominable old places hitherto in use. The old female

receiving ward, a place with a brick floor, lighted by a window in the

roof 18 inches square and thoughtfully provided with two open

ventilators, having been taken as a bath-room, the infant’s school-room

is to be converted into a receiving ward, so that the paupers on their

first admission will have a comfortable apartment with a boarded floor

and well lighted. The same improving hand is visible all through the

house, and everything is done to make life within the walls bearable.

This work has been carried out by the inmates, the only cost being that

of the materials, and those of our readers who may feel inclined

to inspect the place, will, we are sure, in no way begrudge the outlay.

The alterations will all be completed in about a week, or fortnight at

the outside, and we may add that then the master (Mr. H. Sidney) will

be only too pleased what has been effected to anyone who will pay him a

visit. It now only remains for us to congratulate the committee upon

the manner in which they have discharged their duty. The changes have

entailed a large amount of time and thought, but the result fully

compensates for this, and we have no doubt that the Board generally

will thank them most heartily for their valuable assistance."

After this lengthy exposition, one might assume that the Workhouse

would continue for many years, however by the time of an article in The Ipswich Journal (12 September

1896) vigorous discussions were conducted to decide on the contractor

to build a new (replacement) Workhouse on the eastern edges of Ipswich

at Heath Road.

Heath Road Workhouse and

Infirmary

The workhouse in Over Stoke lasted only sixty-two years or so. It

cannot have been built to a good standard as one writer describes it

towards the end of its life as 'crumbling'. After thirty years of

encouragement/demands by the Poor Commission, an expensive (and

extensive) new workhouse was built from 1896 on heathland at the east

end of

Woodbridge Road – today this is known as Woodbridge Road East. It was known

as Heathfields Poor Law Institution and it was one of the last

workhouses built in England. The

redbrick receiving block and Porter's Lodge stood here until late 2015

acting for a number of years as the Borough's

Homeless Families Unit, eventually giving way to a large

modern health centre. The workhouse complex opened in 1899 and was

built with special regard for the sick and elderly; the rest of the

residents were almost by definition deemed lazy or, at best, immoral.

Although listed as having capacity for 400 souls, some say that it was

around 500. By 1912 it housed 385 inmates and 17

officials.

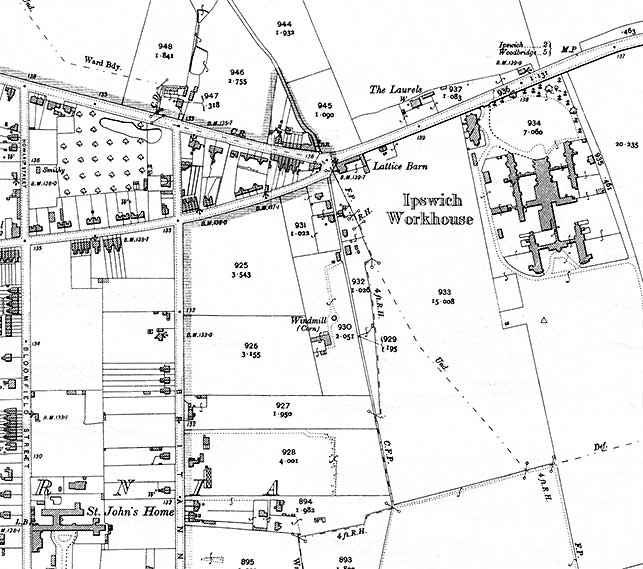

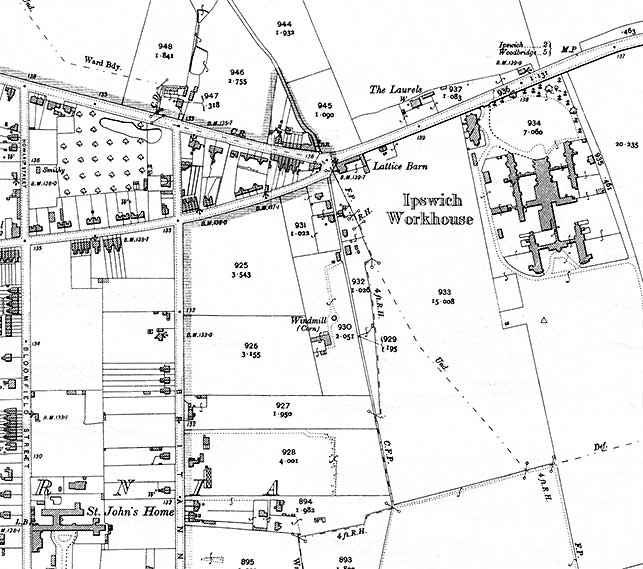

1902 map

1902 map

The 1902 map detail of the north-east corner of the California estate

(above) shows Woodbridge Road running east-west along the upper part of

the image. Spring Road meets it at the 'Lattice Barn' – still standing

at this time (the public house named after it was built over the road).

Working from the far right: Heath Road as we know it today, Lattice

Avenue and Goring Road were yet to be built, as was Colchester Road

which would eventually join Woodbridge Road just east of the Workhouse

Porter's Lodge. The geographical relationship between

the Workhouse and St John's Home (at lower left, as mentioned below) is

clear here.

In the early 20th century it was decided to change the Victorian name

of Union Workhouse to 'Heathfields'. The Union was dissolved in 1930

when Poor Law Unions and their Boards of Guardians were dissolved and

the task of dealing with poverty was made the responsibity of the

Ipswich Corporation's

Public Health Department. The workhouse continued as an 'Old People's

Home' and eventually served as the nucleus of the new general hospital

in the 1970s, eventually replacing Anglesea

Road Hospital in the early 1980s. The site has seen several modern

developments down Heath Road.

St John's Children's Home

During the 1870s up to 235 workhouse children, initially not all from

the Ipswich Union, were rehoused. St John's Children's Home opened at

the southern end of

Bloomfield Street on the California

estate in 1879. See our Brickyards

page for an 1883

map of the Bloomfield Street brickyards showing 'St John's Home' to the

south. Our 1902 map above shown the Home in relation to the Heathfields

Workhouse. 'Freelands' as it became known was demolished in the 1970s

and was

eventually replaced by housing.

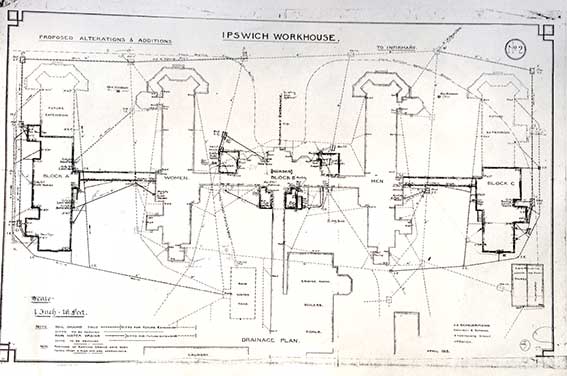

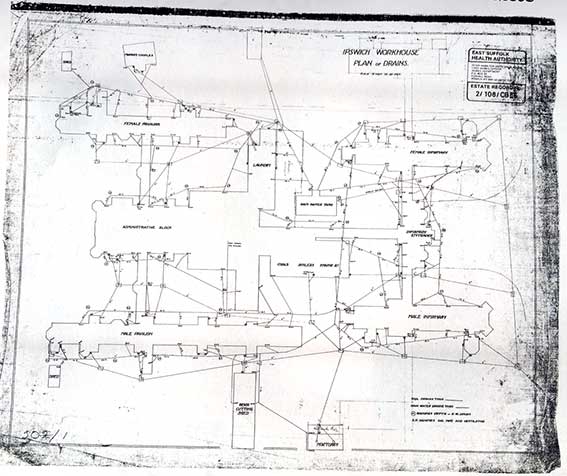

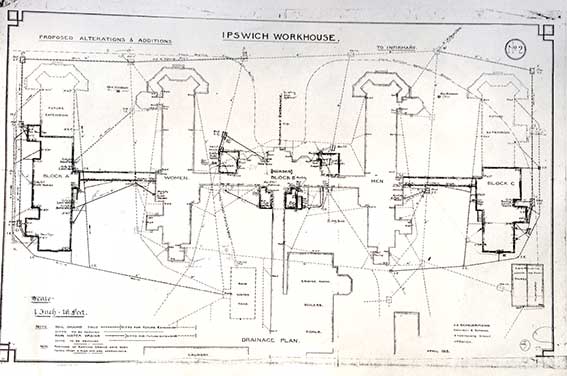

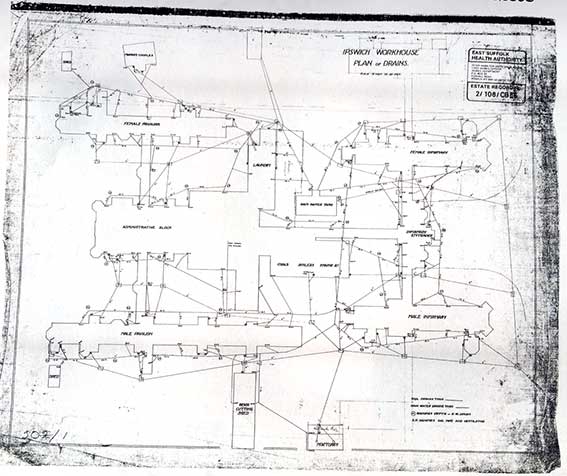

'Thought these might be of interest too although they are

drainage plans they show a basic layout of the workhouse. Kind regards,

Steve Girling'. These plans give an idea of the

'pavillion-style' and extent

of the The Ipswich Workhouse on the east of the town. As so often

occurs, this complex formed the

basis for Heath Road Wing ('H.R.W.') of Ipswich General Hospital,

which supplemented health services provided at the Anglesea Road Wing ('A.R.W.'), which opened

in 1836 as the Ipswich & East Suffolk Hospital. By 1988 all

hospital services had moved to Heath Road and the site at the north of

Berners

Street was used to build a care home, retaining the eye-catcher portico.

Steve Girling's seemingly bottomless archive turns up this

intriguing postcard:

'I have attached a copy of a postcard in my collection of a

group of people with a board written on it "DINNA FORCE, HEATHFIELDS"

on the back of the card is written "Feb 1918". I don't think the

building in the background exists anymore: the building is possibly the

one on Peter [Higginbotham]'s workhouse site [see Links]

in a photo dated c1937. I think this building faced the Woodbridge Rd

side of the site and has been demolished, there is a very similar

doorway still on the site hidden by a modern flat roof extension at the

entrance 15 of today's hospital (also pictured on Peter's site dated

2001) but the windows above the door canopy are different to the

postcard windows.' Thanks

to Steve for this enigmatic image with its even more enigmatic

inscription: 'DINNA FORCE'? The

only linguistic context we can come up with is in the Scottish dialect

e.g. "Dinna force me to answer ye."Presumably,

this is an assemblage of institution staff at the end of the First

World War.

Heathfields in the 21st century

2016 photos courtesy Steve Girling

2016 photos courtesy Steve Girling

'I have attached photos of the concealed door of the old

Heathfields workhouse behind the current entrance 15 at the hospital,

there is also a couple of photos of the date 1898 in the brickwork on

the 'cartouche' at the top, on the photos of the back façade of

the building the 'cartouche' is blank as it would not of been so

visible as it looked over other buildings. Regards, Steve Girling.'

Thanks to Steve for these photographs of the surviving

Heathfields buildings. The dated brickwork tympanum provides

interest on several counts. The beautiful monogram features the

interlaced '1 8 9 8',

although you would have to know a bit of the background to put

the numerals in the correct order (see also the date monogram

in the interior spandrels of the Corn Exchange).

Moreover, we have stated above that 'the new workhouse was built

from 1896'; this suggests that this particular wing, at least, was

opened in 1898.

See the Reading list for Ray Whitehand's

book: Four tenements and a

hay house.

See also Peter Higginbotham's

excellent resource Workhouse: the

story of

the Workhouse in Britain (see Links)

for much more information plus images about Ipswich –

and Suffolk – Union Workhouses.

Home

Please email any comments and contributions by clicking here.

Search Ipswich

Historic Lettering

©2004 Copyright throughout

the Ipswich Historic Lettering site: Borin Van Loon

No reproduction of text or images without express written permission

Photos courtesy Steve Girling

Photos courtesy Steve Girling

Oakum pickers

Oakum pickers

1902 map

1902 map

2016 photos courtesy Steve Girling

2016 photos courtesy Steve Girling