Old Cattle Market /

St

Stephen's Church & Lane / Sir Thomas Rush: his chapel and house

The building in which we're particularly interested is

the

former Blue Coat Boy public house which we mentioned on our More Schools

page in relation to the school sign (now gone) in Curriers Lane.

The metal street sign is a decorative variant on the more heavy-set

cast iron street name signs featured on our Street

Signs page. The six screw heads which attach it to the rendered

wall are picked out in black paint and the curving ogee-type frame has

a sideways fleur-de-lys extending at each side. The satisfyingly

serif'd caps of the name proclaim that 'The Old Cattle Market'

extends to this open area at the top of Silent Street and is not just

the area we now call the bus station.

'The Blue Coat Boy'

2014 images

2014 images

However, the real revelation on this building is tucked under the small

jettied overhang of the first floor. '1620'

which is carved into the

(very narrow) black-stained bressummer beam is a surprise, particularly

as it's so well hidden. Our only worry about the

beam is that it's in

such surprisingly good nick for a 17th century piece of carving; we

suppose that it could be a reproduction installed during one of the

facelifts that these old buildings were often subjected to. However,

the date could well be accurate and it's nice that it still

exists. Thanks to Ken Nichols for the tip-off about this dated

beam. See also the building at the end of Fore

Street which bears a bressummer with the same date.

It's worth comparing with the (also) rather recent-looking '1636' date

on a

building in St

Helen's Street (near Major's Corner), the rather more weathered

'1631' date on the bressummer beams on the Captain's Houses in Grimwade

Street which can be found on the the the Isaac Lord page which is also dated '1636'.

Where once crowds

gathered to witness martyrs being burned at the stake and bulls being

baited, cattle were bought and sold on the Cornhill. The Cattle Market in Ipswich has been pushed to several

locations

as the town expanded and became more crowded, particularly after the

movements of the cavalry through the town started once the barracks

were opened close to Barrack Corner on Norwich Road. The Provision

Market moved from the Cornhill to a one acre site (formerly the house

and grounds of Major Heron) lying between Market Lane - after which it

was named - and St Stephens Lane and opened on Saturday 22 December

1810. You can still see the 'stub' - to use a Wikipedia term - of

Market Street coming off the south side of the thoroughfare called

Buttermarket at the back of the building now housing a coffee

chain, formerly one of several buildings there owned by the firm W.S.

Cowell which combined the businesses of fine printing & stationery,

wine & spirit merchants, tea, coffee and spice merchants, rag

recycling (into printing paper) and home furnishing. The company was

started by Walter Samual Cowell in the Buttermarket in 1818 and after a

long and, towards the end chequered history, this famous firm came to

an end in 1992. The lower end of Market Street, which used to come out

into Falcon Street was cut off by the Buttermarket Shopping Centre in

1986.

When a bigger

location had to be found for the Cattle Market, the owners of the

Provision Market purchased a third of an acre site and added a low wall

and railings, it had a gate onto the top of Silent Street. The site was

not ideal as it was surrounded by a spider's web of small lanes: Dog's

Head Lane was only 15 feet between house frontages. Buying and selling

of livestock

continued on the site we still call 'Old Cattle Market' until 1856 when

the market was moved to the marshy ground near Friars Bridge: you can

still see Friars Bridge Road coming off the north side of the stretch

of Princes Street, close to the Greyfriars roundabout. The land level

was raised about six feet above the surrounding marsh and the Cattle

Market reopened there in September 1856. It continued in operation on

the site until 1986, when a car park was built there. Plus ca change...

See Reading List for Muriel Clegg's 'The way

we went', used for information above.

To the left of the older buildings is a modern structure: Coachman's

Court, the horse-drawn mean of transport once so central to the town's

economy commemorated on the entrance plaque and on the weather vane

high

(and wonky) above.

2014 images

2014 images

Standing with your back to Silent Street, you can spot another OCM

street sign, easy to miss tucked under an overhang of the Buttermarket

Shopping Centre building.

2016 images

2016 images

Sir Thomas Rush and the Church of

St Stephen,

St Stephens Lane

Incidentally, the Church of St Stephen is well

worth a visit now that

it is frequently open as a Tourist Information Centre. This lettered

sheet of lead and its information plaque are displayed in the interior:-

'MR:

JAMES : THORNDYKE

THOMAS : BRISTO,

CHURCHWARDENS

1807'

'Removed from Lead Roof of St STEPHEN'S CHURCH during alteration and

renovation

IPSWICH, September

1937 R.J.

Brady, Rector B.H. Jarman Warden'

Reading: Blatchly, J. Ipswich Tourist Information Centre in the

medieval Church of St Stephen's, Ipswich (see Reading list) is a short, attractive booklet

sold for a pound at our TIC.

See also St Margaret's Church

which carries a similar style – if rather

more chunky – 'T' on a buttress. It is only a few steps

away from here that we find The Sun Inn

(formerly Atfield & Daughter).

The Rush bressumer beam

After the '1620' beam seen in Old Cattle market, another carved

bressumer hangs rather incongruously on the back of

Wilkinson's modern block, facing the east end of the Church of St

Stephen. There

is a small plaque below it which tells

us a little:

'This carved first floor bressummer beam dating from early 17th***

century, and showing an unidentified merchants mark, was retained

by Messrs. J. Sainsbury Ltd. and reinstated here by kind permission

of C&A'. [... the new stores opened in 1971]

The clothing store C&A has long gone from this building,

currently occupied by Wilkinson hardware; Sainsbury occupies the next

shop south of Wilkinson on Upper Brook Street, with a partial frontage

on Dog's Head

Street). Where the bressumer came from isn't recorded on the

plaque,

but it is thought that Rush’s house was located on the place

where the supermarket now stands. The first

shield about a third of the way in from the

left with the 'V' shape is said to be the coat

of arms of the Rush family (however, it is probably Rush's badge as

serjeant-at-arms to the king). The merchant's mark on a

shield beside it is a vertical with

arrow heads at each end and an 'X' at its centre.

The letter 'R' is on a corresponding shield about a third of the way in

from the right. The royal crown is crved at a central position on the

beam. The remaining carving shows

mythical beasts.

Here are the two halves of the bressumer with the central royal crown

shown on both. Scroll down for the bressumer in place on the Underwoods

shop in the 1960s.

2016 images

2016 images

Ken Nichols has supplied this information:

"You requested more information about the 'R' on the beam near St

Stephen's. It is the R of Thomas Rush [or Russhe] 1487-1537 who apart

from being an important man in the town and country funded the

rebuilding (I believe the south area) of St Stephen's Church. There is

also a 'T' for Thomas on the south side (or doorway) I need to check

where, I gained these notes from a town guide."

Another source is Ryan Rush's blog about his ancestor:

"In 1490, Thomas Rush was born in Sudbourne, Suffolk, England. He

gained favour with the Tudor monarchy, first with King Henry VII and

later with his son Henry VIII, who knighted him in 1533 at the

coronation of Anne Boleyn [the year before he was made sheriff of

Norfolk and Suffolk.]. He married Anne Rivers of Ipswich. In 1543

Sir Thomas became the father of another Thomas. This Thomas

served briefly in the House of Commons."

[***Note that Thomas Rush's lifespan of 1487-1537 gives the lie to the

date of "early 17th century" on the beam's information plaque, given

that the bressumer came from Rush's Ipswich house.]

Thomas Rush was a friend of Cardinal Wolsey (c.1475-1530; Henry VIII's

first Lord

Chancellor and Ipswich's most famous son). Rush survived the fallout

from

Wolsey's downfall and attached himself to Wolsey's successor, Thomas

Cromwell. Sir Thomas Rush is interred in the nearby Church of St. Stephen in Ipswich,

which is now the Tourist Information Centre and art gallery. Sir

Thomas' most famous name-bearing descendant is Dr Benjamin Rush,

signer of the United States Declaration of Independence in 1776. Dr

Rush is Sir Thomas' descendant through the latter's eponymous son.

[UPDATE 27.2.2012: Eventually,

in early 2012, we solved the problem of the missing 'T' of 'Thomas

Rush'. It took two visits to St Stephen's Church, two good walks

round the exterior and one round the interior, consultation with the

Tourist Information officer inside, reading of a free sheet on the

church and a 'phone call from within to one of their local history

experts. It is now clear that the wealthy and important Sir Thomas Rush

endowed the church in order that a chapel be built on the south side of

the nave dedicated to him. Looking at the exterior south wall of the

church seems initially unpromising until one realises that the third

buttress down the wall from the 'Wilkinson end' is rather wide and

contains an arch.

Above: to the right of the large buttress is a memorial plaque:

'[Near to this

spot lies the]

Body of JOHN LANGLEY

who Died 15 April 1750

Aged 57 Years.

Also LUKE his Son

who Died 13 Jan. 1742[?]

Aged 28 Years.'

Composite

2016 photograph of the buttress

Composite

2016 photograph of the buttress

The area of interest is above the small blocked arch where a Rush

family crest borne by two angels carved in stone

was once in place in the masonry. The initials

'T' to the upper left and 'R' to the upper right commemorated the

donor; the 'R' is long gone as is the crest. However, if you look

carefully there is a curly initial 'T', roughly

similar to that used on a well-known daily newspaper masthead:

The letterform is one form of the Lombardic

alphabet

and these examples show variants: carved in stone and calligraphically:

Our image includes an enhancement to show

the decorative

character 'T' with hints at the shield shape which seems to have

surrounded it.* There are traces of the decorative scoring which was

incised into the letter. We learn that the blocked arch was a tiny

doorway through the centre of this wider-than-normal buttress; it gave

access to the private chapel. Clearly, they built people much smaller

in those days.]

*See also the Church of St Margaret

for the use of two Lombardic characters in the fabric of the church:

'T' and 'M'.

[UPDATE 19.3.2020: metal

barriers have been erected on this site; one wonders if the once-mooted

sympathetic refurbishment of this buttress is going ahead? The

stonework is certainly cleaner than shown in the 2016 photographs.]

2020

images

2020

images

Once the barriers have been cleared away, we can take a closer look at

the cleaning. The surface does appear to have been scoured. It's

difficult to make out whether the Lombardic 'T' at top left is as crisp

as it was when covered in grime.

2021

images

2021

images

Sir Thomas Rush and Thomas Alvard

Robert Malster in A history of

Ipswich (see Reading list) tells us

more of Sir Thomas Rush and Thomas Alvard following the dissolution of

the monasteries ordered (taking a leaf out of his

former

Chancellor, Wolsey’s book) by Henry VIII.

‘That there were such rich pickings to be had is shown by the fact that

in 1535 the clear temporal income of the Priory of Holy Trinity was

over £69 and-a-half, spiritual over £18 and-a-half, giving a total of

over £88. Primarily the pickings went to the Crown, but there were

others able to pick up a bargain on the way. Two men who benefited from

the events in Ipswich were Sir Thomas Rush and his stepson and

son-in-law Thamas Alvard (Rush married the widow of Thomas Alvard the

elder, Thomas’s mother, and young Thomas married Rush’s daughter by an

earlier marriage). Rush had been made the king’s [Henry VII’s]

serjeant-at-arms in 1508 and continued in the king’s service until

1530s; it may have his familiarity with the court which introduced his

stepson to the service of Cardinal Wolsey at the time he was setting up

his college in Ipswich. The friendship of Wolsey’s servant, Thomas

Crowell, proved an invaluable investment, for when Wolsey fell Alvard

followed Cromwell into the king’s service.

‘Having served as attorney for the college with his nephew William

Bamburgh, Rush was able to offer his inside knowledge of Wolsey’s

affairs to the royal administration; and Alvard was able to do the

same. In doing so they were able to pick up some of the spoils.’ Rush

was on the county commission to enquire into Wolsey's late lands in

1530, and both he and Alvard did well out of the Crown leases in this

property.

Thomas Rush was also elected to represent Ipswich in parliament in

1523. In 1534 Rush and Alvard were elected as joint

representatives of Ipswich to Westminster. Alavard died the next

year and Rush two years later.

Rush and Alvard were canny political survivors and they certainly had

an eye to business. When, after the Cardinal's fall, Wolsey’s college was closed down

and the fabric dismantled and stockpiled on the site, it was

appropriated by the king. Much of it was transported to Westminster (to

be used on the building of Whitehall

Palace?). Some idea

of the scale of the college campus can be guaged from the fact that the

Exchequer accounts of 1531 record 1,300 tons of Caen stone (initially

imported from Normandy – Ipswich doesn’t have local supplies of stone)

and 600 tons of flints (initially brought to Ipswich from the cliffs in

Harwich).

The southern chapel at St Stephen should more correctly be called the

Rush-Alvard Chapel (see the link below to the paper by Blatchly and

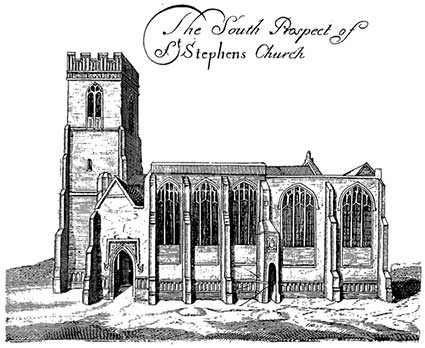

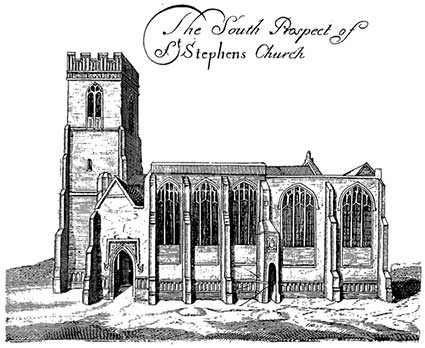

MacCulloch). Ogilby's map of 1674 features illustrations of the

medieval churches in Ipswich including this church, with the doorway

through the central buttress clearly shown:

1674 view

1674 view

Interior

St Stephen has a painted royal arms of Charles II

inside the church. It features, below the royal crest, two small

figures

who reappear in the arms on The Ancient

House, the Church of St Margaret

and the Church of St Clement. For more discussion on this, see our Church of St Clement page under 'The royal arms of

Charles II: who are these people?'.

Sir

Thomas Rush's house,

Upper Brook Street

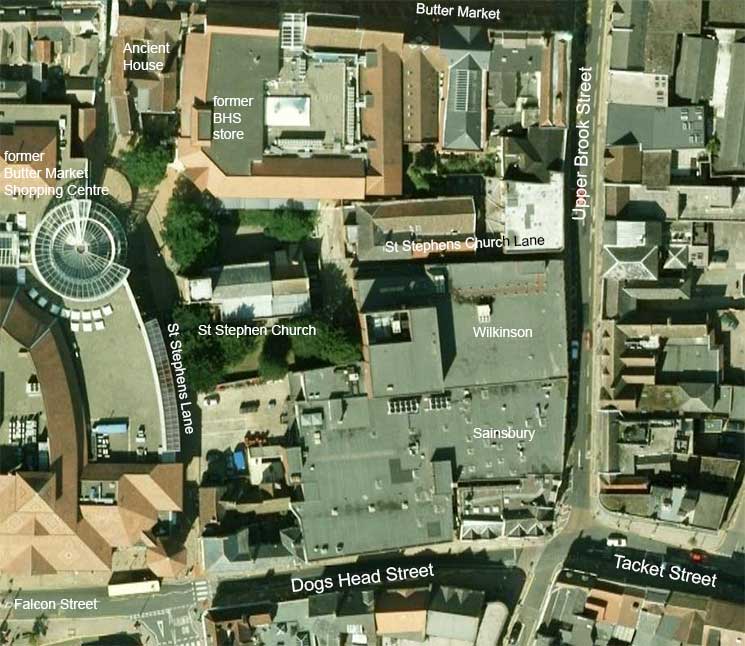

Further research turned up a learned paper by Diarmaid MacCulloch and

Dr John Blatchly published by The Suffolk Institute of Archaeology and

History: 'Recent

discoveries at St Stephen's Church, Ipswich, the Wimbill Chancel and

the Rush-Alvard Chapel'. This splendid piece of work encompasses

all the elements mentioned above and more.

1674 map

1674 map

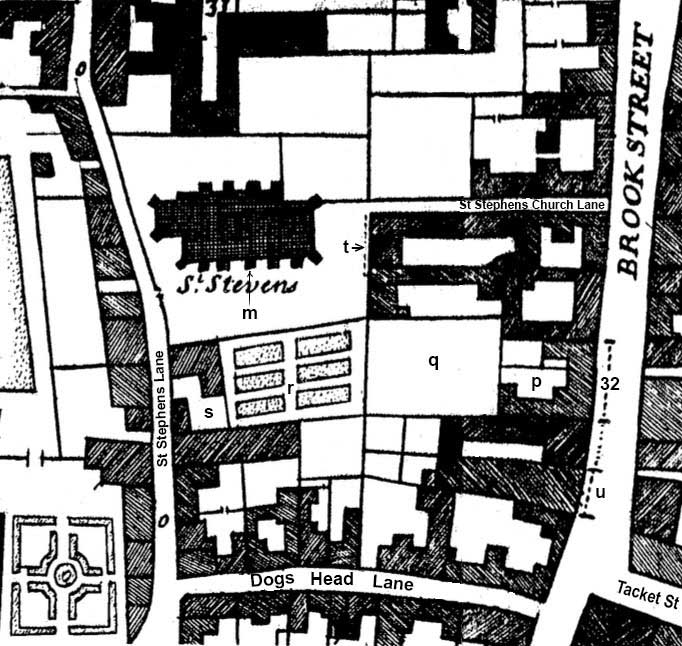

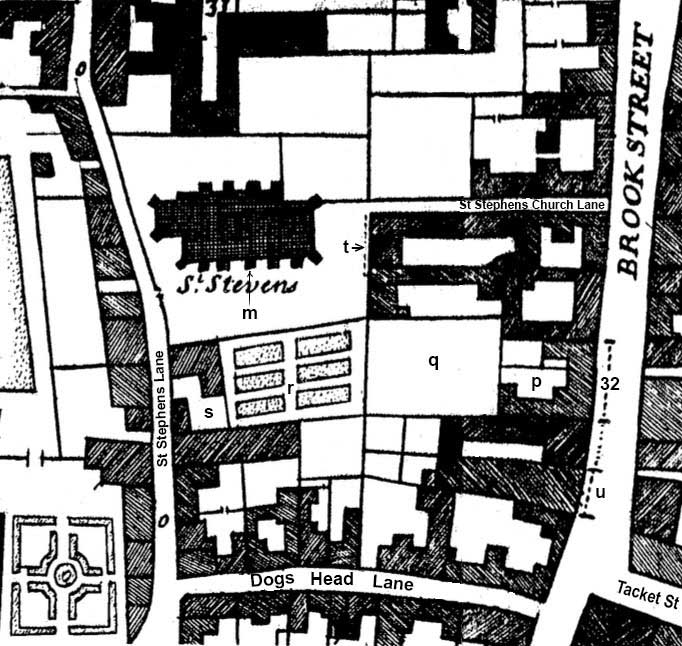

'Using a modified section of Ogilby's map of 1674

(Fig. 22) it

is now possible to show the extent of the Rush premises. The

property (p)

became 32 Upper Brook St., and both Haslewood and Woolnough, who were

able to examine the buildings in the 1930s, suggested

that one or two adjoining properties to the south were once part of the

same building. The carved bressumer was formerly on No. 40 (u),

and it is entirely reasonable that the Rush frontage ran the whole

distance represented by the dotted line. The indenture of 1518 by which

Rush leased the parsonage garden from the incumbent for 99 years at an

annual rent of 4 shillings defines the plot precisely as (r) adjoining Rush's garden (q) to the east and the

parsonage itself (s)

on the west. William Neve, wheelwright, was the occupier to the south.

From his extended grounds Rush could then survey the entire south side

of the church to which he was to add so much. It is appropriate, though

coincidental, that today his bressumer at (t) overlooks the family chapel

[buttress entrance arrowed m],

and that each bears one initial to make up T.R.'

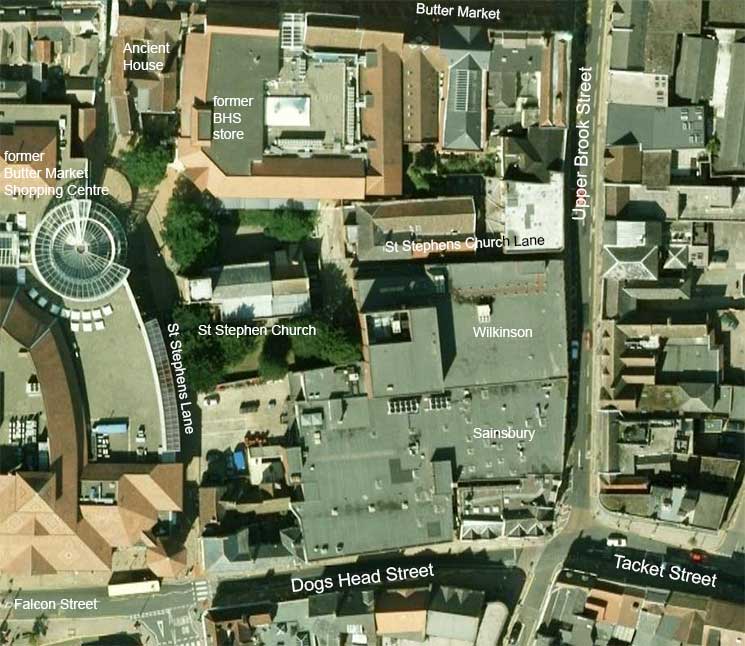

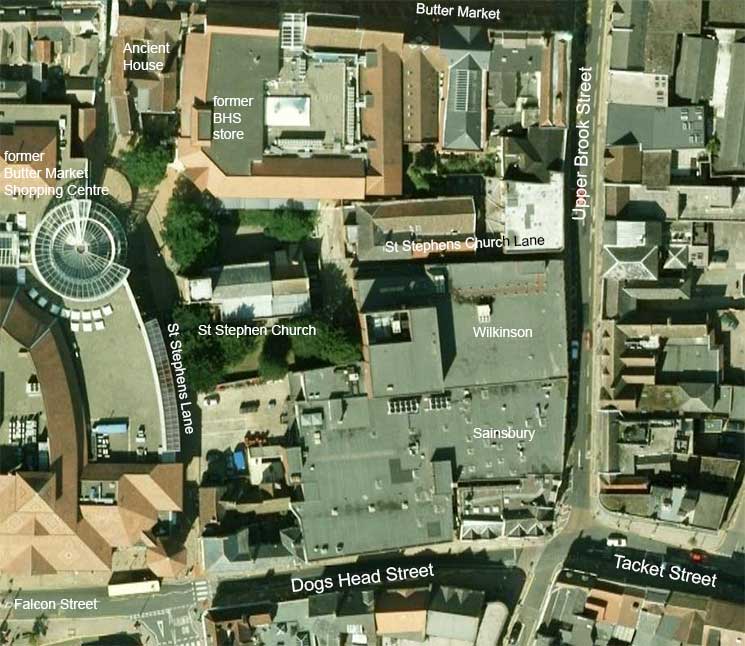

2015 aerial view

2015 aerial view

Below: overlaying up

the 1674 map onto today's aerial view (and lining up the church and St

Stephens Chuch Lane) shows clearly that the Rush bressumer was sited on

a section of the old Ipswich Building Society offices (u) – quite surprisingly close

to the Tacket Street junction. It is clear also that the line of Dogs

Head Street has been altered over the centuries. The potential

frontage of

Rush's house (from u

up to p)

covers the footprint of all of today's Sainsbury's store.

See also our Withypolls

memorials page for Sir Thoma Rush's role (along with his neighbour,

Sir Humphrey Wingfield) in the sale of the

Holy Trinity Priory site and the early days of Christchurch Mansion.

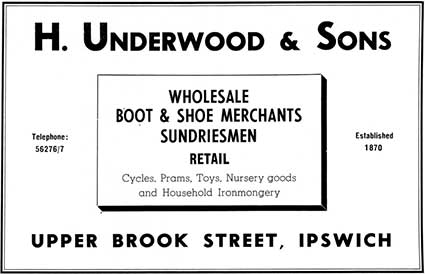

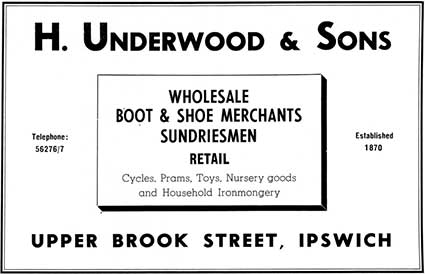

Underwood's shop

'It was in 1970 that all the buildings on the west side of the

street from St Stephen's Church Lane southward (Nos. 28 to 40) were

demolished, and the present C. & A. and Sainsburys premises were

built on the site. Only the elaborately carved bressumer beam from the

street front of No. 40 (next door but one to No. 32) was saved; it is

now mounted on the west wall of C. & A. facing the east end of St

Stephen's church (Fig. 21). The beam has on it three shields which

carry, separately, a merchant's mark, a chevron, and a letter R, also a

Royal crown with dragon and lion supporters. There are winged beasts,

probably gryphons, on either side of the R. Rush's badge as

serjeant-at-arms to the King would have been the Royal crown, and that

and the R on the beam point to him.' (MacCulloch &

Blatchly)

Courtesy Ipswich Society Image Archive

Courtesy Ipswich Society Image Archive

Above: the shops now occupied by Sainsbury and Wilkinson in the 1960s.

Signs for 'Price's Boots' and the 'Coach

& Horses Hotel' (far left)

are visible.

‘HOUSEHOLD IRONMONGERS

H. UNDERWOOD & SONS LTD. 34’

next door to:

‘E.L. HUNT LTD. BUILDERS MERCHANTS’

It is clear from the vertical,

white 'UNDERWOODS' sign that the business occupied the building with

the green signboards and the shop beyond it (which appears to have a

rooftop

signboard, too). The carved bressumer beam from the Rush house was

heavily painted as part of the shop-front

and probably largely unnoticed by passers-by. The remarkable photograph

below comes from The Ipswich Society's Image Archive (see Links). It shows a close-up of the Underwood's

shop sign with the bressumer beneath it.

1960s

image courtesy Ipswich Society

1960s

image courtesy Ipswich Society

Above: a detail from the 'conserved' bressumer currently on the rear of

the replacement building. The paint layers removed, but also a part of

the beam around the tail of the creature to the left of the crown. The

crispness of the carving can now be appreciated. In the days when it

adorned the merchant's house, it would have been colourfully painted,

picking out details such as the blazon and royal crown.

Advertisement 1965

Advertisement 1965

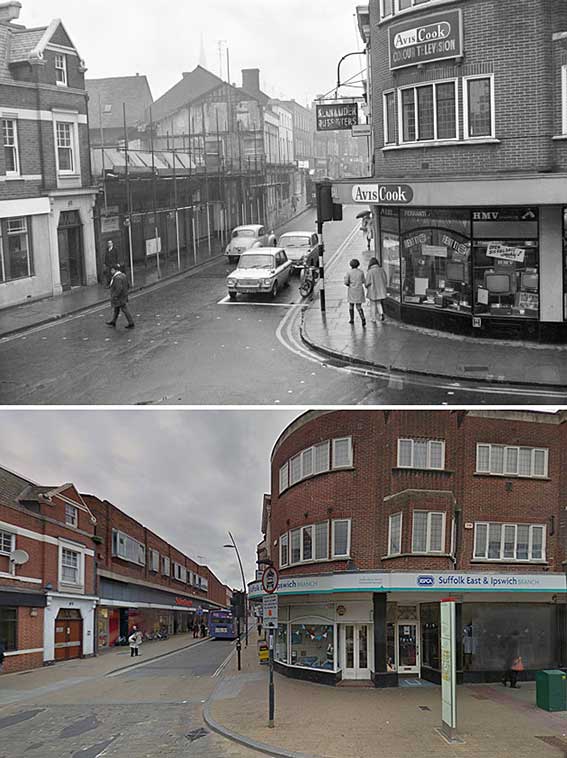

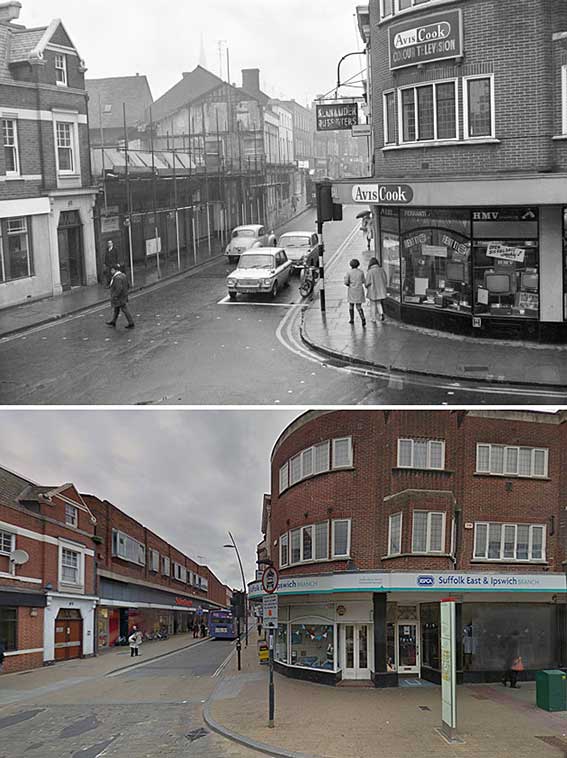

The comparative images below show the clearance of shops

for the

building of the Sainsbury

store on the west side of Upper Brook Street in the foreground. The

northern part of the Sainsbury store would have been the site of Sir

Thomas Rush's house. On the far left is the Ipswich Building Society

branch which is on the corner with Dogs Head Street. On the right is

the curved brick building which in 1934 replaced timber-framed

structures: 'Alexander Outfitters' on the illuminated hanging sign at

first floor level and the Avis Cook audio and television store in the

foreground (1-5 Tacket Street).

The present-day photograph shows the Wilkinson store with St Stephens

Church lane at the right and the beginning of the Sainsbury site at the

left.

Shop addresses in Lower Brook Street

in 2016 (it appears that the numbering of the properties in the

16th century varies from the postal addresses today):

Boreham Christopher Jewellers

26A Upper Brook St, Ipswich IP4 1EB

[St Stephens Church Lane]

Wilkinson store (formerly C&A)

28-32 Upper Brook St, Ipswich IP4 1EB

Sainsbury

38-40 Upper Brook St, Ipswich IP4 1EB

Kaspa’s (formerly Ipswich Building Society offices, formerly The Dog’s

Head In A Pot public house)

42-44 Upper Brook St, Ipswich IP4 1EB

28-32 would appear to indicate the width of Sir Thomas Rush’s house on

Lower Brook Street: the site currently occupied by Sainsbury’s (today

numbered 38-40). Scroll down this page to learn more about the complex

world of Thomas Rush and his remarkable survival as a politician at

Court.

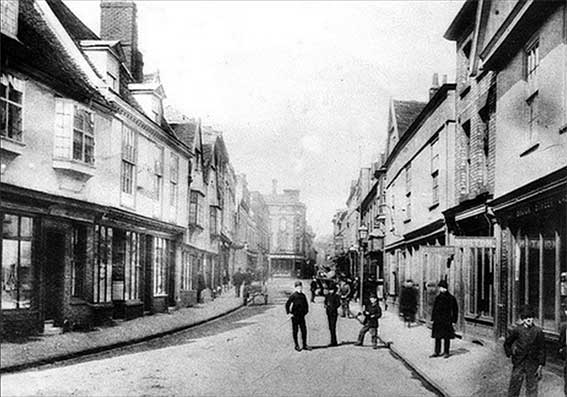

Photo

courtesy John Field

Photo

courtesy John Field

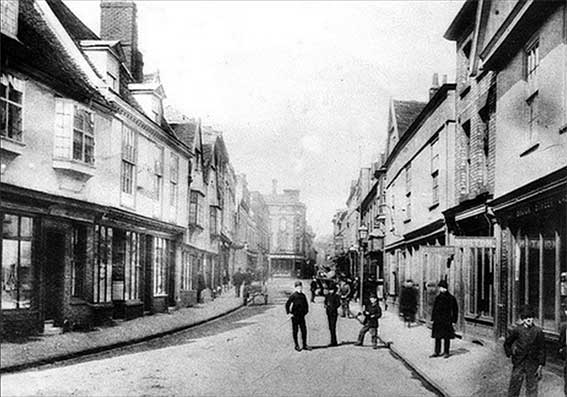

John Field sends this remarkable view of Upper Brook Street with

original timber-framed buildings in

situ. Symonds the chemist's shop

projects dramatically into the road north of the Butter Market

junction, leaving a narrow lane for traffic and pedestrians. This

photograph is clearly taken before road-widening, so pre-1900,

perhaps 1880-90. The shop which John believes was the home of Thomas

Rush is (probably) the one second from the left, with its two dormer

windows: Underwoods shop. It certainly bears a bressumer beam above the

shop-front and presumably it is the beam displayed close to the Church

of St Stephen, to the rear of these buildings. More research to come.

Incidentally, the Ipswich windows at the immediate left remind us just

how many fine – and once wealthy – houses were lost from this street.

Mansions in Ipswich

As a footnote, today's rather uninspiring urban

scene around the southern end of Upper Brook Street was

home to three wealthy, prestigious mansions belonging to powerful and

noble inhabitants.

1. The Duke of Suffolk

had a mansion in

Upper Brook Street, opposite that of Thomas

Rush (1487-1537), not as

we first thought on the site of the building at 39 Upper Brook Street

containing the archway leading to the old Woolworth car park (shown in

the photograph below painted pink and with a balustrade at roof level).

The

current building here was built by Charles Cullingham to act as his

Steam Brewery Tap for the Victorian brewery he built behind it. Both

were later taken over by Tollemache and renamed the Steam Brewery

Inn/Brewery Inn; it closed for business in 1920. The part to the north

of the archway has been empty and near-derelict for years; to the

south, the tiny bag shop Can-Can has operated successfully***.

The late Duke of Suffolk wouldn't recognise the place today. However, Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk

(c.1484-1545), is said to have

lived next door where the former Coach

and Horses Inn, 41 Upper Brook Street, still stands (whose coach houses

may have been the last

remaining

parts of the Duke's house), and adjoining the possible Brandon property

fronting Tacket Street. The Coach and Horses Inn operated as a coaching

inn from 1787 or earlier and closed for business in 1977. It is now

mainly a charity shop, but still bears the 'Winged Wheel' symbol of the

Cycling Tourist Club, as described on our Roundels

page. For a 1902 map of this area see our Symonds

for Kodaks page; it clearly shows an 'Inn' to the north and an

'Hotel' to the south of the entry.

[***UPDATE November 2018: The

Steam Brewery Tap/Tavern has, at long last, been modernised and rescued

from dilapidation, forming a retail shop fronting Upper Brook Street

with, presumably, separate accommodation behind. It's no longer pink.]

2016 image

2016 image

2. The town house built by Sir Humphrey

Wingfield (c.1481-1545) of Brantham Hall, some four miles

south of the town on the Suffolk-Essex border. It

fronted Tacket

Street and is described on our Courts &

Yards

page in the section marked 'Tankard Street'.

3. Thomas Seckford's (1515-1587)

'Great

Place' in Westgate Street as described in our Lost Ipswich signs page under the section

'Before Willis'. Another perhaps surprising mansion –

more of a palace.

4. Hatton Court, off Tavern

Street, was the site of the home of Christopher Hatton (1540–1591) who

was born and lived in a fine White House, now replaced by an 18th

century house of timber, brick and plaster: the corner house (Listed

Grade II), now Church's Bistro with a wing at nos. 2 and 3 Hatton

Court (now part of McDonald's). He was considered a 'liberal patron of

learning and eminent for his piety, charity and integrity.' Sir

Christopher ingratiated himself, by his elegant and graceful dancing,

into the favour of Queen Elizabeth I and became Lord Chancellor in

1587. Which reminds us of that other Lord Chancellor from Ipswich,

Thomas Wolsey (c.1475-1530) who had his eye on...

5. The town house of Robert styled

'Lord' Curson (c.1460-1534/5) on St Peters Street, described on

our Curson Lodge and Wolsey's College pages.

6. Stoke Hall, next to St

Mary-At-Stoke, Church was built by the wine merchant Thomas Cartwright in 1744/5 and was

later occupied by the engineering entrepreneur, Robert James Ransome

(1830-1891).

7. The wealthy merchants of the town

would want a central, prestigious

house as they gained great riches. Henry

Tooley, William Smart, Robert Felaw, Richard

Purplett and others would be amongst them. It would only be in the

19th century that, to escape the overcrowding and pollution, the

wealthy would seek to build their houses in the leafier surrounding

areas (see, for example Upland Gate).

All this is a testament to the social, political and economic

significance of Ipswich throughout history and particularly in the 15th

and 16th centuries.

Our Roundels page repeats the above

photograph with others of this location with further commentary.

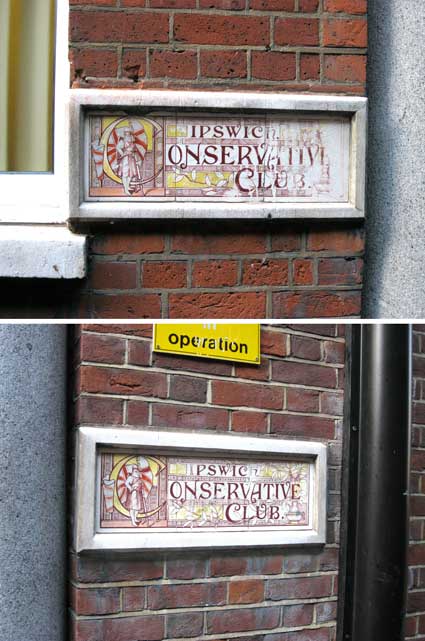

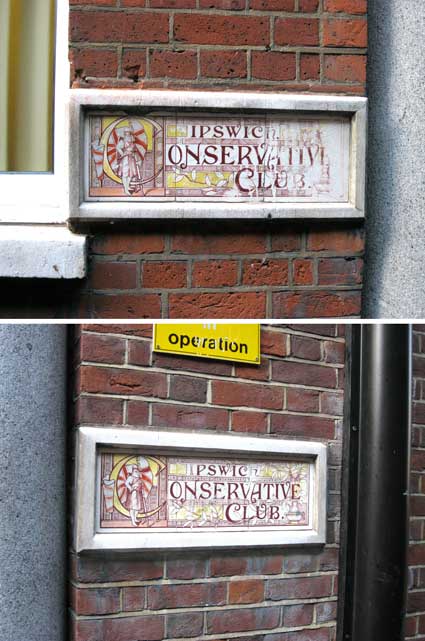

The Conservative Club, St Stephens Church Lane

2014

images

2014

images

2018 image

2018 image

We had dismissed this lettering for many years, perhaps

because of politics, perhaps because it has always looked worn and run

down. However, in updating the St Stephens Church section (above), we

passed it again and decided it ought after all to be included. The left

panel is in rather poorer nick than the right, perhaps due to vandalism

(it doesn't say much for the quality of the ceramic tiles which make up

the signs), but the figure of the crusader bearing the huge Union Flag

banner is unmistakable. The yellow has worn better than the blue, it

must be said. The entrance to:

'IPSWICH

CONSERVATIVE

CLUB'

is in a narrow passageway leading from the church to

Upper Brook Street called St Stephen's Church

Lane. This is distinct from St Stephen's Lane which leads up from Dog's

Head Street, past The Sun Inn and

–

after Arras Square – runs up alongside The

Ancient House to come out opposite Dial

Lane. See our Soane Street page for a

note from Dr James Bettley regarding the Freemasons' move from this

building in St Stephens Church Lane to the new Freemasons' Hall near

Christchurch Mansion.

The metal

street sign at the Upper Brook Street end

The metal

street sign at the Upper Brook Street end

At a later visit we noticed some lettering on the wall adjacent

to The Conservative Club and towards St Stephen's Church (close to the

Con Club "smoker's ghetto"):

'E.L.D.

C.H.D.'

with

a stone block set into the wall above it, resembling a boundary

marker(?). See our gallery of Boundary

markers for information and images. What do the initials stand for?

2014 images

2014 images

Now that we know that this building was the original home of the

Freemasons, perhaps this has a bearing on the initials. We assume that

they relate to Worshipful Masters or Grand Viziers of the day. This

original

Masonic Hall is the design of E.I. Bell (the only work by this

architect in Ipswich, we think) in 1865. To confirm the Masonic

connection, at the eastern end of the building is an external apse (an

arc of a circle in plan) shown below; this appears to be a convention

for Masonic Lodges, providing an 'altar' feature in the main meeting

hall(s). A similar feature can be seen on our Soane

Street page, along with the original foundation plaque for this

earlier Lodge.

2018 image

2018 image

An unprepossessing set of palings hides bins and other clutter, but the

apse is clearly visible. A few yards from here is The

Sun Inn, reputed to have been commissioned to be built as a Masonic

Hall in the 17th century.

Another one bites the dust... 26 Upper Brook Street

[UPDATE 25.3.25: 'I may be a

bit late to the party but I've just spotted this old Thomas Cook

signage on Upper Brook Street next to St Stephens Church Lane. Premises

had been used by Cancer Research since at least 2009. Ed Broom'. Thanks to Ed for spotting this curiously

'negative-space' shop sign (photographer and bicycle shown in

reflection). Presumably a contractor took the trouble to knock out the

plastic characters of the shop sign. Having been founded in 1841 and

becoming one of the most familiar names in holiday travel, the Thomas

Cook Group went into liquidation in 2019.]

2025

image

2025

image

The complex world of Thomas Rush and

his son-in-law, Thomas Alvard (taken from the MacCulloch &

Blatchly paper – cited above, under the heading "Sir

Thomas Rush's house")

'The genealogy of the Alvards and Rushes is complicated enough, but

once one starts examining their affairs, a picture of equal complexity

emerges, of connections administrative, commercial and official, among

layman and cleric, amid town and country. If Anne Rivers' first two

husbands had careers which were conventional enough, Thomas Rush's was

of quite a different sort. His pedigree's significant silence about his

origins indicates that they were obscure; he probably came from

Lincolnshire, for his career was founded on his service to the

Lincolnshire and Suffolk aristocratic family of the Lords Willoughby of

Eresby, who brought several Lincolnshire families to live in south-east

Suffolk. He was among Christopher Lord Willoughby's servants when

Willoughby made his will in 1499, and he would be William Lord

Willoughby's executor in 1526; he made his home at Sudbourne near the

Willoughbys' Suffolk headquarters at Orford, and had much to do with

the nearby monastery at Butley, which had strong Willoughby

connections.' It was probably through his influence that his

brother-in-law Augustine Rivers moved from being Prior of Woodbridge to

become Prior of Butley (a much larger Augustinian house) in 1509; Rush

and his son-in-law the younger Thomas Alvard would remain close

associates of Rivers' successor, the Sudbourne boy Thomas Manning, last

Prior of Butley. Rush was steward of both Woodbridge and Butley

Priories in 1535.

Quite early in his career, however, Rush's Willoughby links seem also

to have given him an entrée into royal service. He was already

described as the King's servant in 1508, when he was made

Serjeant-at-Arms; in 1513 he was seeing service in the first of Henry

VIII's absurd French military adventures, and he would continue to

serve in the wars. From 1517 he was enjoying a shilling a day from the

Crown for life. He was made a Knight of the Sword at Anne Boleyn's

coronation in 1533. It was probably his familiarity with the Court

which introduced his stepson and son-in-law Thomas Alvard to the

service of Cardinal Wolsey, perhaps appealing to the belated sense of

affection for his home town which the Cardinal discovered after his

visit of 1517; the Wolsey connection brought them an invaluable future

investment in the shape of the friendship of Wolsey's servant Thomas

Cromwell. When Wolsey's credit collapsed in 1528-9, Alvard and Cromwell

would hasten into the King's service, and they would continue to have a

fruitful relationship; Alvard and Rush, with their friend Prior Manning

of Butley, would be Cromwell's most valuable contacts in Suffolk during

the 1530s.

The way in which Rush and Alvard followed Cromwell into the royal

service is neatly illustrated by their involvement in both the creation

and the destruction of Cardinal College,

Ipswich. Rush served as attorney for the College with William Bamburgh

(his nephew and Alvard's brother-in-law), and he was naturally

prominent among those giving presents to the College on its opening in

1528; equally naturally he was the recipient of College leases.

However, when Wolsey's crash came and the lands of his foundation were

dispersed to suit the King, Rush and Alvard could offer the royal

administration their inside knowledge of Wolsey's affairs in

supervising the carve-up, and could also do themselves a good turn in

picking up some of the spoils; Rush was on the county commission to

enquire into Wolsey's late lands in 1530, and both he and Alvard did

well out of the Crown leases in this property. Why not? It was too late

to save the College, and their old master ,the Cardinal, was past

harming.

Why did Rush decide to make an alliance with the Ipswich Alvards rather

than among the Suffolk county gentry? Perhaps his Lincolnshire origins

and their obscurity meant that he was not acceptable in county society,

and so he chose to make his way into the very separate world of the

merchants of Ipswich; in the event, both his wives would be the widows

of wealthy Ipswich merchants. His marriage to Anne Rivers meant that he

inherited the elder Alvard's capital messuage in St Stephen's parish,

to which in 1518 he added a garden of the parsonage leased from Thomas

Paccarde the incumbent. It would be natural for him to mark his

steadily more successful career by building on Alvard's foundation of a

temporary four-year chantry service in the church to create a family

aisle fit for the dignity of a Knight of the Sword. It is worth noting

that he handed over the office of Customer at Ipswich to his associate

John Valentine (another Wolsey servant) in 1528; presumably by this

time he felt that such a local commercial association was not

appropriate to his status.

By this time, of course, Rush was fully integrated into the county

elite outside the town of Ipswich, havingbecome a county J.P.

sometimebetween1520 and 1524; his son joined him on the Bench in 1534 —

a mark of the family's unusual status, for the Crown was normally

reluctant to allow father and son to sit together as justices. This was

a mark of Cromwell's high trust that the Rushes would serve his and the

King's purpose in the county. By now family marriages were beginning to

reflect this enhanced status: matches were arranged with Suffolk gentry

families with Court links like those of the Rushes themselves, bringing

in daughters of Sir Anthony Wingfield and the Duke of Suffolk's servant

Nicholas Cutler.

The younger Alvard and Rush were both buried in St Stephen's; Rush's

will is lost, but Alvard in his requested a marble stone showing his

arms in the church. No doubt the monuments of the Rush and Alvard

families were of the highest quality as befitted wealthy and powerful

people. That Anne Rivers had a second memorial is indicated by the

fifth coat of arms noted by William Tillotson in the church c. 1594. Of

ten coats, the relevant ones are 4 Alvard; 5 Rush impaling Rivers; 7

Alvard; 9 Alvard impaling two coats: Rush and Darcy. The ninth coat

will presumably have been on Alvard's marble stone; he must have

married a Darcy before predeceasing Rush in 1535.

Although Rush seems to have been buried in the aisle which he had so

lavishly created, there is no surviving evidence of a memorial for him.

This may be because his eldest son Arthur died only a month after him

in July 1537 and left a son and heir who can have been little more than

a baby; Thomas Cromwell was Sir Thomas's chief executor, and it is

likely that the political excitements of the next three years,

culminating in his own fall and execution in 1540, distracted him from

providing a monument. It may have been in the confusion of his fall

that Rush's will disappeared from his papers; there is no evidence of

probate. William Bamburgh of Rendlesham, one of the other executors and

another old Willoughby servant from Lincolnshire, was preoccupied with

disputes over the earlier will of the younger Thomas Alvard (his

brother-in-law), and he also became entangled in a dispute with Sir

Thomas's grandson, Anthony, over the administration of Sir Thomas's

goods which dragged on as late as 1561, resulting in Bamburgh losing

the administration. Meanwhile Sir Thomas's second wife, Christian, was

caught up in the years after his death with her own set of testamentary

disputes over the will of her first husband, the Ipswich bailiff and

M.P. Thomas Baldry; in any case she may not have taken much interest in

a chapel associated with Sir Thomas's first wife Anne. With such a

combination of mishaps, it is hardly surprising that the Rush chapel at

St Stephen's seems like an enterprise still-born. No later members of

the family appear to have taken any interest in it.

Nevertheless, what had been erected in the Rush Chapel probably

remained in a reasonable state up to the Civil War (1642–1651).

Tillotson was able to note the heraldry of the monuments in the 1590s;

Blois saw the main Alvard stone apparently intact on his visit, but in

October 1657 Candler recorded sadly that 'the brasse hath been taken of

from all the old monuments for lucre thereof in the times of the late

unhappy warres'. His phrase seems specific enough to suggest that the

brasses were removed for money before the visit of William Dowsing*, a

supposition strengthened by the fact that Dowsing found only one

'popish inscription in Brass, pray for the Soul', on his visit on 30

January 1644. The Alvard — Rivers — Wimbill matrix remained to be drawn

by Davy in August 1829, so its burial must have taken place during the

last century restorations. It lay in 1829 where it was found buried in

1985, near the centre of the western bay of the chapel. Today, this

slab and the single Lombardic letter T on the external aisle buttress

are the only remains to testify to this mausoleum of a remarkable trio

of men of affairs, their much-married spouses and their uniquely

labyrinthine genealogies.'

[*William Dowsing (1596–1668)

was an English iconoclast who operated at the time of the English Civil

War. Dowsing was a puritan soldier who was born in Laxfield, Suffolk.

In 1643 he was appointed by their captain-general, the Earl of

Manchester, as 'Commissioner for the destruction of monuments of

idolatry and superstition' to carry out a Parliamentary Ordinance of 28

August 1643 which stated that 'all Monuments of Superstition and

Idolatry should be removed and abolished', specifying: 'fixed altars,

altar rails, chancel steps, crucifixes, crosses, images of the Virgin

Mary and pictures of saints or superstitious inscriptions.' In May 1644

the scope of the ordinance was widened to include representations of

angels (a particular obsession of Dowsing's), rood lofts, holy water

stoups, and images in stone, wood and glass and on plate.

Dowsing carried out his work in 1643–44 by visiting over 250 churches

in Cambridgeshire and Suffolk, removing or defacing items that he

thought fitted the requirements outlined in the ordinance. He recruited

assistants, apparently among his friends and family, and where they

were unable to perform the work themselves he left instructions for the

work to be carried out. Sometimes the local inhabitants assisted his

work, but often he was met by resistance or non-co-operation. His

commission, backed up by the ability to call on military force if

necessary, meant that he usually got his way. He charged each church a

noble (a third of a pound) for his services.

When Manchester, his patron, fell out with Oliver Cromwell in late

1644, his commission ceased. Dowsing is unique amongst those who

committed iconoclasm during this period because he left a journal

recording much of what he did, with many detailed entries.]

Home

Please email any comments and contributions by clicking here.

Search Ipswich

Historic Lettering

©2004 Copyright

throughout the Ipswich

Historic Lettering site: Borin Van Loon

No reproduction of text or images without express written permission

2015 aerial view

2015 aerial view

2014 images

2014 images

2014 images

2014 images

2016 images

2016 images

2016 images

2016 images

Composite

2016 photograph of the buttress

Composite

2016 photograph of the buttress

2020

images

2020

images

2021

images

2021

images 1674 view

1674 view 1674 map

1674 map 2015 aerial view

2015 aerial view

Courtesy Ipswich Society Image Archive

Courtesy Ipswich Society Image Archive 1960s

image courtesy Ipswich Society

1960s

image courtesy Ipswich Society

Advertisement 1965

Advertisement 1965

Photo

courtesy John Field

Photo

courtesy John Field 2016 image

2016 image

2014

images

2014

images 2018 image

2018 image The metal

street sign at the Upper Brook Street end

The metal

street sign at the Upper Brook Street end

2014 images

2014 images 2018 image

2018 image 2025

image

2025

image