Withypoll memorials,

Holy Trinity Priory and its church

This feature of Christchurch history had escaped our attention,

until Mike Taylor, Senior Conservation Officer of Ipswich Borough

Council, drew our attention to it. The location of this large stone

slab is at the back of a stretch of lawn to the right of the front

elevation of Christchurch Mansion. Because it is set back and, until

recently (July 2019), overgrown by vegetation, many people, we suspect,

missed by many. Mike arraged for the old, overhanging

yews and ivy to be removed (with replanting to follow). Does the

slab hold the key to the story of Holy Trinity Priory and Church?

2019

images

2019

images

The following photographs scan down the length of the slab. It

is clear that some indentations are still discernible and others have

weathered. 'Laboratory-condition' photography in half-light with raking

light would reveal more.

Richard Edgar-Wilson, Chair of the Friends of Ipswich Museums,

and Carrie Willis, Duty Officer for Colchester & Ipswich Museums,

are to be credited with providing the following information. Our thanks

to them, particularly for bringing to light the 1977 research paper on

the memorial.

Richard writes:

'This is an interesting slab, and yes, the whole history of Holy

Trinity seems peculiarly opaque. I have attached a document I have in

my files called Notes on Holy Trinity

(collected from various sources and not verified) which might possibly

have some information you do not already know.

The go-to person re: the slab would have been the much missed John

Blatchly. But luckily, John wasn’t the sort of person to leave a stone

unturned! Thanks to Carrie Willis, Duty Officer at the Mansion, who in

January [2019] raised the possibility of somehow restoring or at

the very least saving it from the elements, we have this information

which John and Diarmaid MacCulloch wrote in a piece called 'An Ipswich

Conundrum: The Withypoll memorials’ in the Transactions of the Monumental Brass

Society. I have taken the liberty of forwarding Carrie’s précis

here. Incidentally, I wonder whether the William Dandy

mentioned is actually a Daundy,

of Wolsey family fame? I would like to see the slab taken inside. If

not into the Mansion, then perhaps one of our magnificent churches (or

indeed ex-churches).'

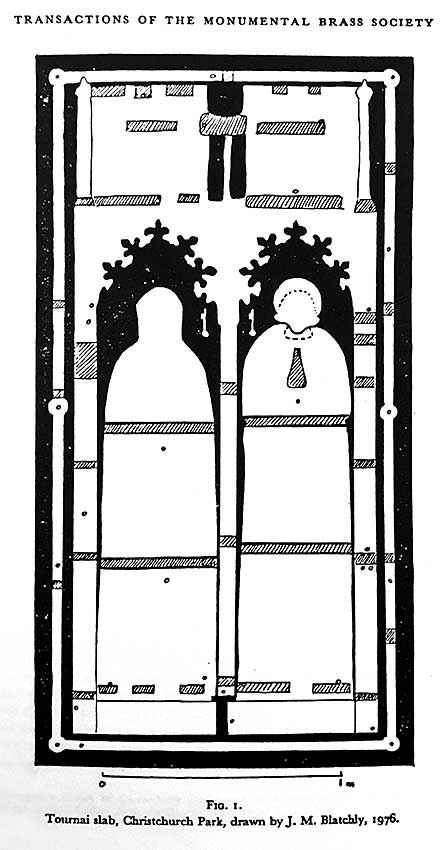

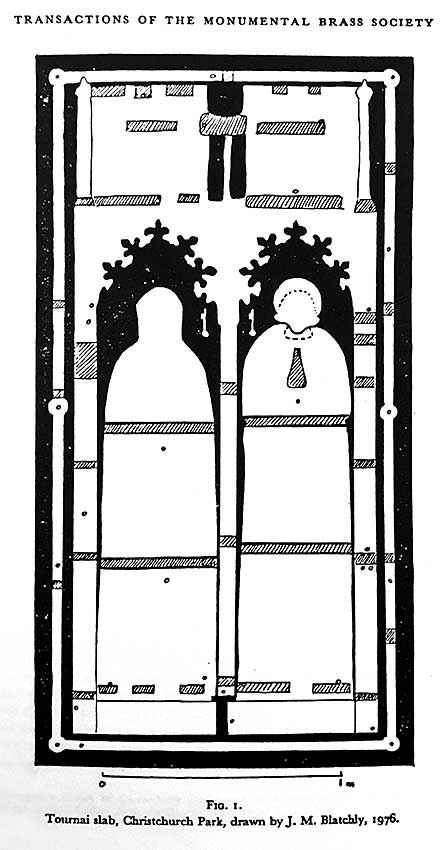

"An Ipswich

Conundrum: The Withypoll memorials

It is a remarkable 14th century brass indent.

The Tournai marble*** slab measures 1.6 metres x 3.16 metres and

although considerably

worn and damaged, it retains the indents of two figures under a double

canopy, all inside a marginal fillet. The figures appear to be a woman

wearing a cowl head-dress on the dexter side and a civilian wearing a

coif on the sinister.

A strange feature of the slab is the presence of two indents of keys

beside the heads of the figures, presumably either a badge of office or

some sort of heraldic or punning device. Prominent also on the

slab are the indents of various backing strips which would be soldered

and riveted to the large areas of brass plate to join them together;

apart from these, only 35 dowel holes are now visible.

The figure of the civilian also retains a deeper indent of praying

hands to be inlaid in white marble or alabaster, and there are traces,

now indicated only by the greater depth of the surface of the stone

from the plane, of similar indents for the hands of the lady and for

the faces of the two figures. (See the tracing below)

The use of inlay of this sort and of Tournai marble, besides the

general use of the slab, indicates that this is not English work. there

is little doubt that it was made in Flanders, either at Tournai itself

or at Ghent or Bruges; its date is c.1320-30. Such slabs are almost

unknown in England, but in Scotland they are a good deal more

common. It is in Scotland that one finds exact parallels for the

Ipswich indent. These come respectively from Dundrennan Abbey in

Galloway and St John's Burgh Kirk, Perth, and the details of the design

particularly the canopy in both cases is such as to leave little doubt

that they are from the same workshop as the Ipswich slab.

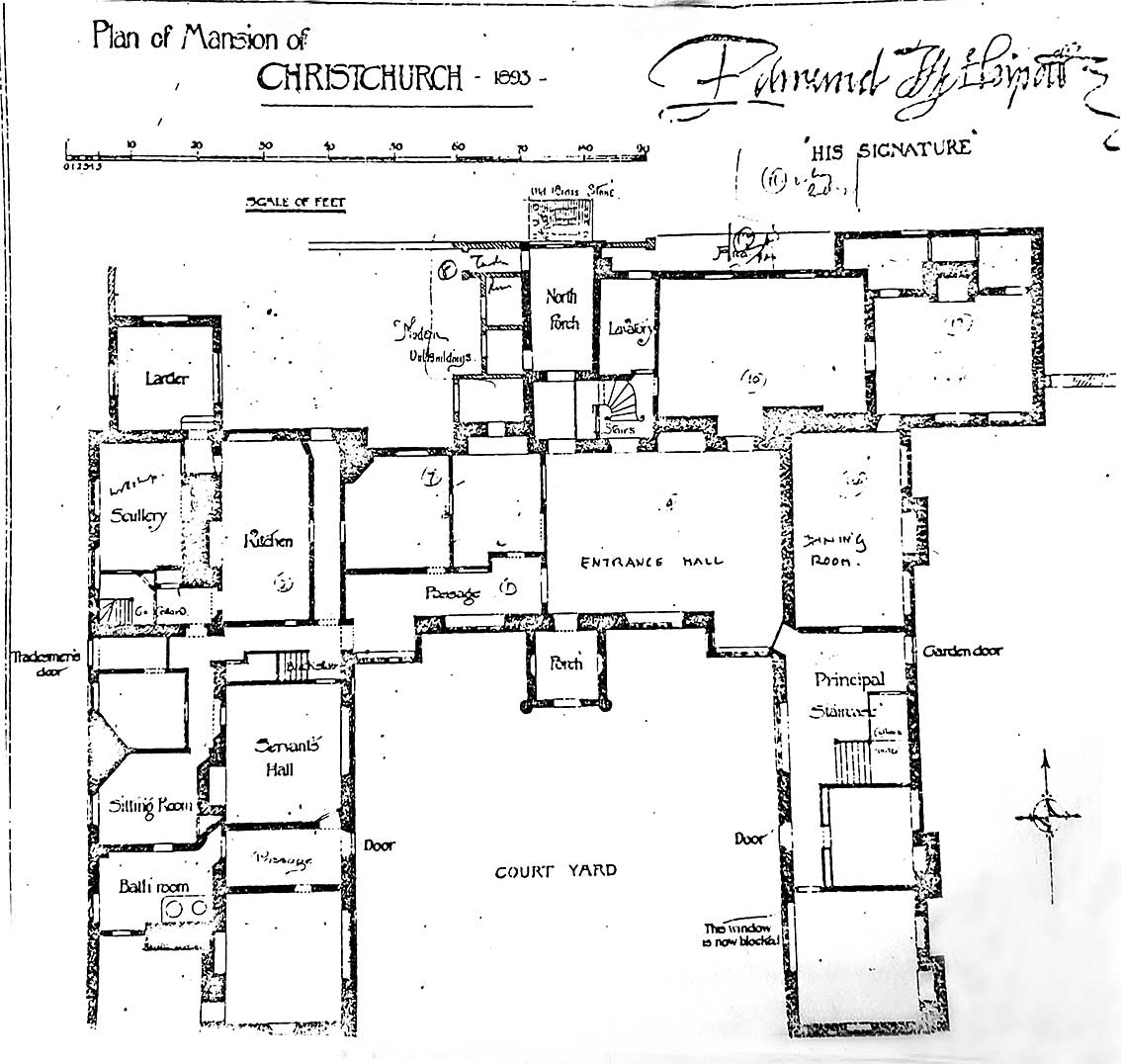

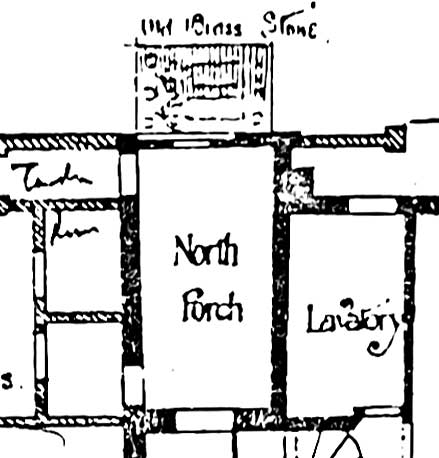

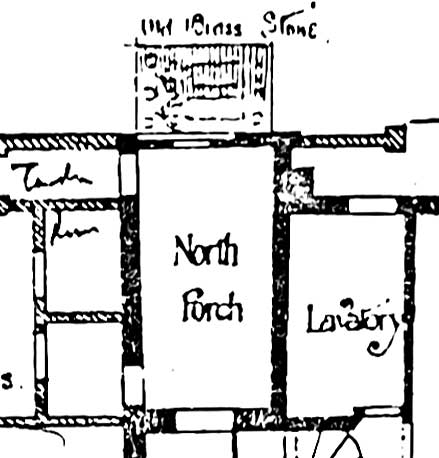

Nothing is definitely known of this slab until 1888, when the local

antiquary Hamlet Watling wrote an article for the East Anglian Daily Times. He

described

the slab as then 'serving the purpose of a doorstop outside the

Conservatory' at Christchurch; this was confirmed 5 years later when

local architect and historian, J.S. Corder, produced Christchurch or Withepole House: a brief

memorial (1893) in which he

mentioned the slab 'without the north door of the present mansion doing

duty for a step' and so illustrated it on his plan. (See the Mansion

plan below.)

It is unlikely that the slab can have been in such a position much

before 1888, otherwise the degree of deterioration would be greater, it

is equally unlikely that it had been a recent arrival at Christchurch,

or else the Victorian commentators would surely have known of its

introduction. Presumably it had been found face down somewhere in or

near Christchurch.

MacCulloch and Blatchly allude to the slab being intentionally used by

Edmund Withypoll as his grave stone in St Margaret's. In his Will of

1568 Edmund instructs 'to bee buried in the chauncell of St Margarets

parishe in Ipswich where I dwell under the northe windowe there with

the greate stone'. Clearly this is a different monument to the one in

the Church as the present slab was placed by Withypoll six years later

and not in the North window but in the centre of the church (now

moved).

Sometime in 1563-5 William Dandy, of Ipswich, bought a law suit against

Withypoll in which he stated that Withypoll had seized land belonging

to his family in Clay Street, now Crown Street. When William

Dandy had gone overseas to persue business he left the land in the

hands of his widowed mother Joan. Edmund Withypoll entered the

premises, pulled down the boundary fence and expelled Joan and the

complainant. Withypoll took away a tenter leased to some cloth

workers 'and also taken awaye one great black grave stone of the value

of xxs thear standing by the said grange and caryed awaye the same to

his owne howse in Yippiswiche'. Is this the slab noted in

Edmund's Will? If so, its rather dubious origins might explain why in

1574 Withypoll decided to replace the tomb of which it formed a part

with an entirely new monument and slab.

If this is the slab we can deduce that the stone came from the Dandy

family. The Dandy family were engaged with Maritime trade with Northern

Europe. Ipswich had long been a centre for trade of mill stones,

monumental slabs, sculptured stones. At Ipswich the dues from imports

of stones had come to be reserved for the benefit of the wardens of the

important borough guild of Corpus Christi. Its important to note that

William Dandy was elected Guildholder in 1555 with Matthew Butler and

William Barker and would thus have been drawing these profits for

themselves. It is probable therefore to suggest that Dandy

acquired the slab from one of these Northern European or Scottish

ports.”

[Based on the article by John M. Blatchly and Diarmaid

N.J. MacCulloch. Transactions

of the Monumental Brass Society, 12, pt.3

(1977), pp.240-7. Accompanying drawing below.]

(***scroll down for a geological opinion on the mineral

involved.)

Notes (second papragraph): in heraldry, 'dexter' is to the

right, 'sinister' is to the left; 'coif': a woman's close-fitting cap.

Notes on Holy Trinity Priory

- The Covent at Holy Trinity was at no time large, it

consisted of a

Prior with 6/7 Canons. In later times the Covent may have had as many

as 20 Canons. The premises at Holy Trinity were not of considerable

size.

- In about 1870 some alterations being made in the Bowling

Green, on the

east side of the Mansion, uncovered the site of the Priory tower. The

foundations were blown up by gunpowder. [Scroll down for a 1780 map.]

- King Edward I visited the Priory on the 8th January 1296

on the

occasion of his daughter's wedding at St Peters. He left 7 shillings

for

his oblation at the Great Altar and another 7 shillings at the Shrine

of relics. [See our King Street page for

an account of this royal wedding in Ipswich.]

- On the 16th January 1296 Lord John de Wickham, on behalf

of the King,

offered to the Priory a silver cup with a foot and cover, weighing four

marks, less 20 pence.

- In 1522 Cardinal Thomas

Wolsey obtained his 1st Bull for

the suppression

of certain

religious houses to aid the funding his college in Oxford.

- In 1528 Wolsey obtained his 2nd Bull for the suppression

of St Peters

and other monasteries for his college in Ipswich. [A Papal Bull is a

type of public decree, letters patent, or charter issued by a Pope of

the Roman Catholic Church.]

- Wodderspoon* and other writers assert that Holy Trinity

was

suppressed

for these purposes. Neither the Inquisition of Cromwell, The Papal

Bull, the Inspeximis of

Henry VIII, nor the Fine with the Dean and Master of the College of the

Blessed Mary in Ipswich, contain any reference to Holy Trinity. [*Memorials of the ancient town of Ipswich

in the county of Suffolk / by John Wodderspoon. 1850.]

- Two later Bulls were obtained, one of which was certainly

comprehensive

enough to have embraced Christchurch, but Wolsey’s fall precluded any

further action under the powers granted to him. The Priory was

eventually suppressed under the Act for the Suppression of the lesser

Monasteries, extorted from Parliament by Henry VIII, in February 1536.

- The Prior undoubtedly received a meagre pension, and the

last glimpse

of him was in the Ministers Accounts

of Norfolk and Suffolk from

Michealmas 1540-1541. It is recorded that the Prior of Holy

Trinity had

died since the last account.

- The land was leased by the King to Sir Humphrey Wingfield

and Sir

Thomas Rushe by deed dated 10th March 1537, for a term of 21 years

at

the rent of £90 19s 4 1/2d.

- The site included, house and site, houses, barns,

edifices, yards,

gardens, orchards, ponds and fishponds – adding up to 643 acres. This

land included the manors of Christchurch, Coddenham, Cretyng and

Stonham.

- The site was bought from Wingfield and Rushe by Sir Thomas

Pope and

sold on to Paul Withypoll for £2,000.

- Within two years of Paul’s death in 1546 Edmund, his son,

started

building. Debris was incorporated from the Priory into the foundations

and wall linings of the Mansion. A Stables and well House were also

built from the spoils.

- 1548 marked the commencement of building; it was seen as a

splendid Mansion

because of the material used: red brick and masonry.

Note that the oldest examples of lettering on this website are

the

painted glass 'Seals of Holy Trinity' which survived the demolition of

the Priory Church which can today be seen in the

vanished church's Victorian namesake: the Church

of Holy Trinity in Back Hamlet.

Christchurch/Holy Trinity timeline

to 1895 (compiled for

the Friends of Christchurch Park).

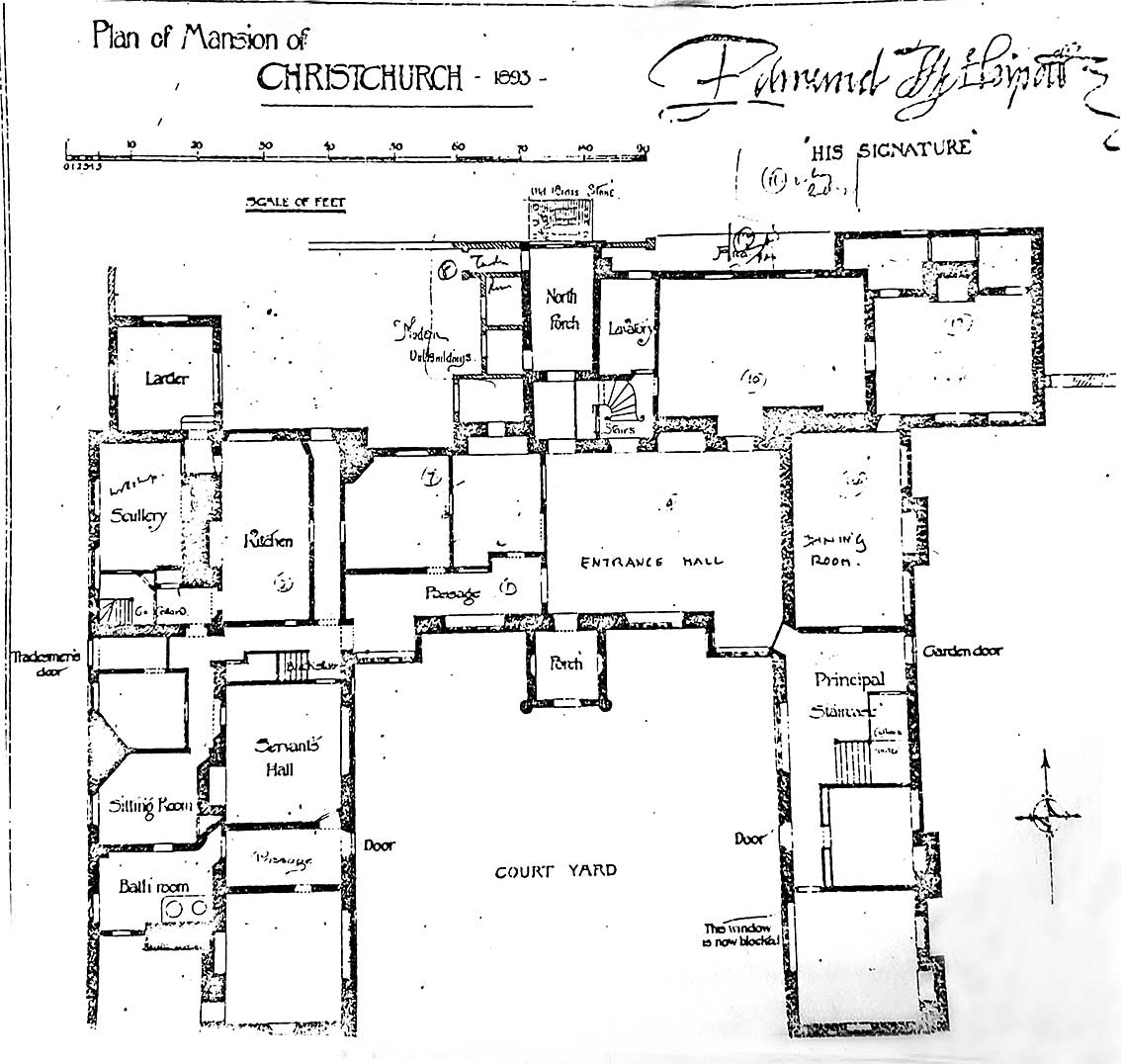

Plan drawing of Christchurch Mansion,

1893

Detail of the plan of the Mansion (built after the Dissolution of the

Monasteries in 1536), drawn by John Shewell Corder (with some hand

additions) showing the position

of the 'Old

Brass Stone' to the north:

Detail

of the 1893 plan

Detail

of the 1893 plan

The mineral used for the 'Old

Brass Stone'

Caroline Markham of GeoSuffolk: 'Bob and I visited the medieval slab

behind the Mansion this afternoon and it tested (very) positive for

CaCO3. So it is definitely a limestone, which means that Tournai

Marble (which is a limestone) is not precluded. However, the slab is

grey (quite pale grey really) and so does not present as classic

Tournai Marble which, as we all know, is black*. Because it is grey, it

is probably a Carboniferous Limestone rather than the creamy Caen Stone

or Northamptonshire Limestones more common in old Suffolk buildings.

The nearest sources of Carboniferous Limestone are Derbyshire and

Belgium. Belgium could well have been easier for transport at that

time, so the Belgian origins in the document you sent me have some

justification.'

[*The most notable local example of masonic Tournai marble is the 14th

century font at the Church of St Peter, which is dark grey/black in

colour (below).]

Archeaology

The archaeology beneath and around the Mansion could reveal much of the

story and position of the original Holy Trinity Priory and its Church.

Is it possible that the Mansion stands on the site of Holy Trinity

Church itself? The east-west alignments of the Mansion and St Margaret

is striking.

https://heritage.suffolk.gov.uk/hbsmr-web/record.aspx?UID=MSF4957-Augustinian-Priory-Christchurch-Park-Ipswich-SPECULATIVE.-(Monument)

The above link shows the record held on the Suffolk

County Council database for this site and the limited work which has

been done so far.

1780

map detail

1780

map detail

The Hodskinson & Jefferies map of Ipswich,

1780 shows the position of the Mansion (here marked 'Chrifts

Church'), south of the Round Pond,

also the Church of St Margaret (built c.1300 as a Chapel-of-Ease to the

nearby

Holy Trinity Priory Church when the congregation became unmanageable in

the original church – now demolished) with the 'Bowling Green'

between them. See note 2 of the 'Notes on Holy Trinity Priory' above

regarding the archaeological discovery c.1870 beneath the Bowling

Green, soon destroyed by gunpowder.

The location of Holy Trinity Priory

Church

[UPDATE 31.7.2019: Mike

Taylor, Senior Conservation Officer at Ipswich Borough Council writes:

'Thankyou for this update, which adds the interesting information about

the location of the church tower. Keith Wade [former County

Archaeologist], the archaeologist on our

Conservation Panel, also thought the church was next to Bolton Lane and

was not a large structure. The timeline mentions a rebuilding and

a royal visit, so it may have acquired size following modest

beginnings. It’s a shame they dynamited the site without recording the

position of the tower – Norman churches often had central towers, and

the choir /presbytery to the east would probably have benefitted from

investment more than the nave to the west (hence perhaps the need for a

completely new church at St Margarets). The evidence is, as you say,

elusive, but I still think the odds are in favour of this stone being

the one surviving fragment from the old church.' Many thanks to Mike for this and for

sowing the seed for this web-page. This will clearly be a mosaic of

small

pieces of information, but we may eventually help in piecing together

the story of the Priory Church and its location.]

'Medieval

It is to the foundation in the 12th century of the Augustinian Priory

of the Holy Trinity that the original existence of the parkland can be

attributed; the park includes a major portion of the precinct of this

significant post-Conquest religious house. It is likely that all of the

buildings within the monastic precinct lay in the south eastern part of

the later parkland and is probable that the priory church lay at least

partially under the mansion. One small archaeological intervention

recorded a small amount of fabric within the mansion whilst tradition

points to the priory church tower surviving well into the 17th century

before being blown up with gunpowder. This tower may relate to a

structure recorded east of the mansion on the earliest maps.

'Some of the landscaping and management of natural water supply still

seen in the parkland lakes and terraces originated in this period.

Early maps demonstrate a sequence of ponds in the western part of the

park, fed by the natural springs that now feed the Round Pond and

Wilderness Pond. Documents indicate that former medieval ponds supplied

the monks with carp, tench, roach and gudgeon. There may also be

substantial components of the priory's water supply system lying

underground in the park. The main conduit is believed to lie between

the water source formerly on Westerfield Road and the buildings of the

priory around the later mansion site, whilst a main drain should lead

downhill from this location. Allen's work on Ipswich's water supply and

Breen's re-analysis of this suggest that a late medieval water conduit

lay just below the ground surface along Dairy Lane, a former street now

subsumed in the south western part of the park. Remains of Dairy Lane,

the conduit, and any other associated structures may survive.

'Post-Medieval

In 1536, during Henry VIII's dissolution of the monasteries, the priory

was suppressed and its estates seized by the Crown. Paul Withypoll, a

successful London merchant, bought the site in 1545 and in 1548 his son

Edmund began to build a house on the ruins of the priory.

'The mid-16th century post-dissolution private house, now Christchurch

·Mansion, is a Grade I Listed Building, being an almost complete and

comparatively unaltered example o f a brick-built house of the period.

'Throughout its long history, Christchurch Mansion belonged to only

three families. In 1645, the estate passed to Elizabeth, wife of

Leicester Devereux, who was the only daughter and heir of Sir William

Withypoll. In 1735, the house was sold to Claude Fonnereau, a wealthy

London merchant, of Huguenot decent. Either he or his son Thomas made

alterations in the early 18th century. A new wing was built on to the

north-east corner to contain a drawing room downstairs and a

magnificent state bedroom upstairs. The bedroom contains some

outstanding rococo plasterwork incorporating the coat of arms. In 1892

Christchurch Mansion was bought by Felix Thornley Cobbold who presented

it to the people of Ipswich. It was opened as a museum in 1896.

'The position of the house in relation to the southern part of the park

strongly suggests that the original 16th-century building would have

possessed formal gardens arranged in front of it to the south. Some

information on the plan of these gardens ought to be recoverable

through archaeological means, including both geophysical survey and

excavation. Historic maps indicate that there were large formal gardens

in the 17th century spanning the whole southern part of the park.

Again, remnants of these may survive.

'In addition the re-working of the monastic water supply to provide

water for the house (and reputedly for a lead-lined conduit to the

town), may well have resulted in the revision of the medieval works,

traces of which will almost certainly lie beneath the ground here.

'The 18th-century rebuild may also have precipitated garden re-design.'

The above paragraphs are an extract from Christchurch

Park, Ipswich: An Archaeological Desk-Based Assessment and

Archaeological Condition and Management Review by

Paul Spoerry (2003, Cambridgeshire County Council commissioned by

Ipswich Borough Council). We are indebted to the Suffolk

County Council Archeological Service for this information.

Christchurch Park, Ipswich: summary

of main points

‘An understanding of this site based only on the map evidence is

misleading. The documentary sources that have been examined for this

report suggest that the northern part of the park beyond the immediate

area of the house cannot be accurately described as a park until the

middle of the 17th century. Before that date the area was pasture, part

of the demesne land of the manor of Christchurch. The boundaries of the

demesne as shown on John Kirby's map of 1735 include lands that had

been part of the demesne of the former priory but the boundaries had

been straightened and fenced by Edmund Withypoll after 1548.

‘In around 1567, Edmund Withypoll had created what is now known as the

Wilderness Pond. Before that date, there were just four ponds all

probably situated in the south-west corner of the park below a terrace

of formal gardens to the west of the present mansion.

‘The entrance to the park from Soane Street was created or enlarged by

Withypoll after he built his house. In order to widen this entrance

various houses were demolished and the boundary of St Margaret's

churchyard altered. The present churchyard walls were built after 1568

and are not the priory's walls. The main entrance to the priory may

have been from Bolton Lane.

‘The conventual buildings were demolished by Withypoll but remnants of

the church tower survived to the early 18th century. Below the building

to the west was a terrace garden and orchards which backed on to the

ponds. The priory buildings probably dated from the late 12th century

with a few later additions.

‘The priory acquired amongst its early the Domesday Church of Holy

Trinity and it is known that some of the priory's founders were buried

within the conventual church. It is likely that the site of the church

and the land to the south includes a burial ground for both the priory

and possibly for the late Anglo-Saxon parishioners of Holy Trinity.

‘The importance of the southern area of the park which has been a

meeting place "Thingstead" since at least the 11th century should be

emphasised. A fair was held in this area from before 1189.

The park's springs have supplied the town with water from the medieval

period, if not before. They were a source for some of the streams which

formerly ran through the town and were later a source for part of the

town's elaborate medieval water system.’

Anthony M. Breen, July 2003

(quoted in Paul Spoerry, September 2003, cited above)

John Shewell Corder's book

“The seat of Christchurch

derives its name from a Priory of Regular Cannons of S. Augustine,

founded in the Church of The Holy Trinity, a little prior to A.D. 1177,

just without the North gate and Ramparts of the town of Ipswich. On the

authority of Tanner, Holy Trinity was a parish church, and Taylor says

it was originally parochial. In the Domesday Book, Ipswich Half Hundred

on land which Roger Bigot* had charge of in hand for the King, it is

recorded that: “In the said Borough, Anulfus the priest has a church,

Holy Trinity, to which belongs twenty-six acres in alms.” The church, a

small building, abutted towards the East on Thingstede Way since called

Bolton Lane, and the parochial limits were probably co-terminous with

those of the present parish of S, Margaret.

“The seat of Christchurch

derives its name from a Priory of Regular Cannons of S. Augustine,

founded in the Church of The Holy Trinity, a little prior to A.D. 1177,

just without the North gate and Ramparts of the town of Ipswich. On the

authority of Tanner, Holy Trinity was a parish church, and Taylor says

it was originally parochial. In the Domesday Book, Ipswich Half Hundred

on land which Roger Bigot* had charge of in hand for the King, it is

recorded that: “In the said Borough, Anulfus the priest has a church,

Holy Trinity, to which belongs twenty-six acres in alms.” The church, a

small building, abutted towards the East on Thingstede Way since called

Bolton Lane, and the parochial limits were probably co-terminous with

those of the present parish of S, Margaret.

“It was by no means uncommon for a Priory to be established in a parish

church, the nave being left open for the parish altar. This was the

case with the Austin Cannons at Thornton, Carlisle and Christchurch

(Hants), and with the Secular Cannons at Hereford and Chichester.

“It may have been that this church was served by Secular Cannons from

Saxon times.”

[Secular Cannons were much like ordinary priests. They may well have

lived apart, rather than together under one roof – which would explain

the smallness of the Priory; many were engaged in parochial duties.]

“The church, like most Saxon edifices, was not probably a very

substantial structure, consisting as most of them did, largely of

timber, for a few years after [c.1177] it was nearly demolished by

fire, with the adjacent offices. It was rebuilt by John of Oxford,

Bishop of Norwich, formerly Dean of Salisbury and Chaplain to Henry II,

about 1190, who seems this year to have been at his Manor of Wykes

Bishop, whereupon King Richard I. gave the patronage to him and his

successors A.D. 1193-4.”

– Extract from Corder, John Shewell: Christchurch

or Withepole House: a brief memorial.

Cowell, 1893 (copies can

be viewed at Suffolk Record Offices). As well being a noted architect

and architectural illustrator, Corder was clearly an assiduous

historian, too. The plan of the Mansion reproduced above was drawn by

Corder.

[*Roger Bigod (died 1107) was a Norman knight who travelled to England

in the Norman Conquest. He held great power in East Anglia, and five of

his descendants were earls of Norfolk. He was also known as Roger

Bigot, appearing as such as a witness to the Charter of Liberties of

Henry I of England.]

See also the extensive Christchurch

Park &

Mansion page, Christchurch Park Cenotaph, the Ipswich Martyrs monument and the Christchurch timeline.

Home

Please email any comments and contributions by clicking here.

Search Ipswich

Historic Lettering

©2004 Copyright

throughout the Ipswich

Historic Lettering site: Borin Van Loon

No reproduction of text or images without express written permission

2019

images

2019

images

Detail

of the 1893 plan

Detail

of the 1893 plan

1780

map detail

1780

map detail “The seat of Christchurch

derives its name from a Priory of Regular Cannons of S. Augustine,

founded in the Church of The Holy Trinity, a little prior to A.D. 1177,

just without the North gate and Ramparts of the town of Ipswich. On the

authority of Tanner, Holy Trinity was a parish church, and Taylor says

it was originally parochial. In the Domesday Book, Ipswich Half Hundred

on land which Roger Bigot* had charge of in hand for the King, it is

recorded that: “In the said Borough, Anulfus the priest has a church,

Holy Trinity, to which belongs twenty-six acres in alms.” The church, a

small building, abutted towards the East on Thingstede Way since called

Bolton Lane, and the parochial limits were probably co-terminous with

those of the present parish of S, Margaret.

“The seat of Christchurch

derives its name from a Priory of Regular Cannons of S. Augustine,

founded in the Church of The Holy Trinity, a little prior to A.D. 1177,

just without the North gate and Ramparts of the town of Ipswich. On the

authority of Tanner, Holy Trinity was a parish church, and Taylor says

it was originally parochial. In the Domesday Book, Ipswich Half Hundred

on land which Roger Bigot* had charge of in hand for the King, it is

recorded that: “In the said Borough, Anulfus the priest has a church,

Holy Trinity, to which belongs twenty-six acres in alms.” The church, a

small building, abutted towards the East on Thingstede Way since called

Bolton Lane, and the parochial limits were probably co-terminous with

those of the present parish of S, Margaret.