King Street / Lion Street / The Golden Lion /

Arcade Street

2001

images

2001

images

At the Princes Street end of the very

short stub of

King

Street running behind the Exchange

Chambers, we find the

lettered corners

of the building above. The details below

show the enhanced lettering a little better:

'KING STREET'

in bluish

drop-shadow

caps painted over in creamwash also appears at the Arcade Street end

(shown on the left image, above). Also on the Princes Street corner,

darker plain caps spelling out 'KING ST'

on the

block

below are obscured by years of dirt. In between, there is:

'H

26 FT'

indicating the position of a water hydrant. Part

of the

modern metal street sign

can be seen at far left. Below this, against the grubby stonework, is:

'KING ST.'

Upper part of 2001 enhancement (below) – Princes Street end:

Lower

example is Arcade St end (includes full stop)

Lower

example is Arcade St end (includes full stop)

We're almost certain that this unique surviving

example of painted street name lettering was quite clear and sharp

until

summer, 2003. At this time some swine had painted over the lettering at

each end of King Street with cream masonry paint; the letters are still

just visible. Typical. See the 1910 photograph of this corner below.

[UPDATE May 2015: However, we

just

found the painted lettering 'Lion Street' (without drop-shadow) on the

stonework of the Town Hall; scroll down to see it.]

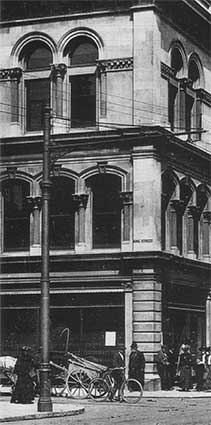

Here is a photograph of the junction of what we now call King Street

and Princes Street (the rear of the Town Hall visible to the upper

right) just prior to demolition of the pub - note the barriers round

the

site. The corner pub, The Sickle (which has the name 'Noble'

above the windows and door on the Princes Street side and was probably

formerly called The Wheatsheaf) will soon give

way to the new Corn Exchange (opened in 1882, see our Cornhill 2 page). It is possible that both

pub names came from the figure of Ceres on top of the first Corn

Exchange nearby which carried a sickle and ears of wheat. Interesting

to see that

the three-storey

right-angle corner

has been built as a curve right up to the roof and is lettered to

advertise the Sickle's wines and spirits and other attractions. Next door is the

'KING'S HEAD COMMERCIAL INN' labelled in a strip above the first floor

windows.

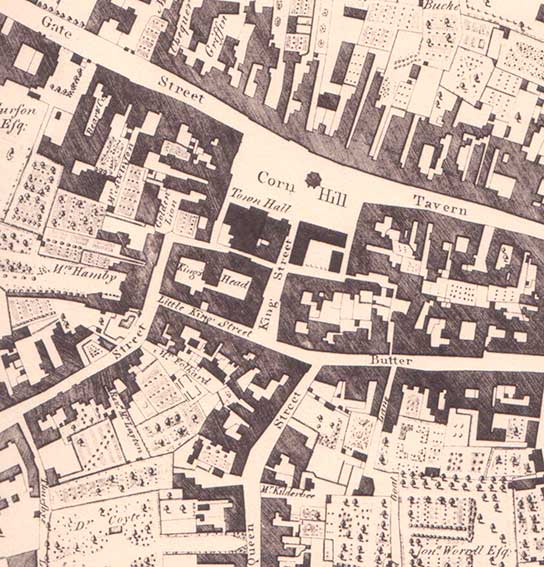

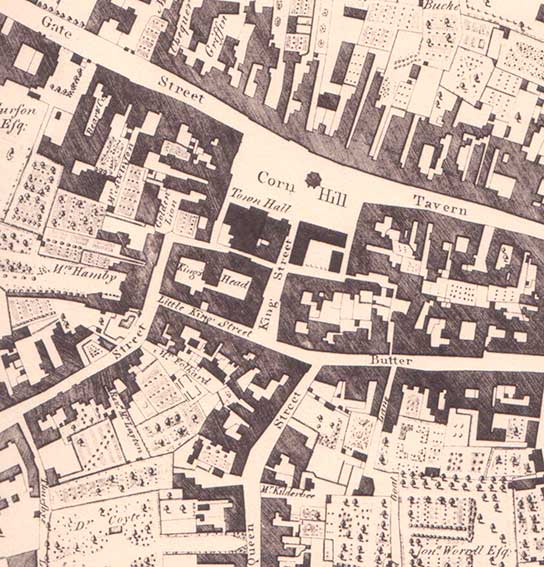

1778 map

1778 map

Derivation of King Street

The name 'King Street' has wandered around Cornhill

in

a bewildering fashion over the centuries. The present King Street was

Little King Street on Joseph Pennington's 1778

map (detail above). The name may have originated from the

King's Head Inn (opened in 1531 and demolished 1880/1 to make way for

the Corn Exchange), seen in the above view, which was possibly on or

near

the site of a building

called the King's Hall where Edward I (reigned 1272 to 1307) feasted at

the time of the

marriage of his daughter Elizabeth to the Count of Holland in 1297. So

the King's Head, which appears to occupy the whole footprint of the

future Corn Exchange on the 1778 map, may

have been named after

the ancient 13th century hall***. See the following caveat:-

‘Although the Cornhill retained its name, the long

roadway to Stoke Bridge saw some changes. Until the late eighteenth

century, it was King Street. Parts of the street had their individual

names, Sennicolastrete 1344, St. Peter’s Street, 1761, which seems very

late, Bridge Street and Queen Street, 1778. But the name King Street

clung to the upper part of the street until it eventually became part

of Princes Street. Even then the name was not lost for what had been

Little King Street or Lower King Street became King Street. It is

tempting look for a particular royal connection, in which case Edward

I, whose visit to the town during the winter of 1296-7 was full of

colourful incident, and with whom an otherwise unknown King’s Hall is

associated, appears to be the likeliest candidate. Regretfully, it has

to be said that the name King Street is often a mistaken rendering of

of the familiar ‘king’s highway’ (vicus

regis). It may be so here.’ [Clegg, M. Streets and street names in Ipswich

(see Reading list)]

A passageway on the line of the Thoroughfare ran

westwards between the rear of the Moot Hall (or Town Hall) and the

King's Head, which is shown on the map as a continuous building with

two central courtyards. This was one of the town's most ancient inns:

one of only twenty-four to appear on a town assessment of 1689. It was

a notorious venue for cock-fighting in the 18th century. These premises

were listed in the 1844 White's Directory, with carriers operating from

the inn to Bergholt. By 1865 it was called the Old Kings Head. Note

that the Market Cross (removed in 1812) is clearly shown at the upper

centre of the 'Corn Hill' in 1778. The old Shambles, at this period

showing signs of decay, was directly south of the Market Cross,

replaced by the Rotunda, the first Corn Exchange and eventually by the

Post Office building. Immediately east of the Palladian-fronted Moot

Hall on the Cornhill were two buildings: an old pub originally the

Three Tuns Inn but more recently named The Corn Exchange Tavern, and

Richard Cole’s shop.

***Here's a

fascinating article from The Ipswich Society Newsletter, July

2018 (Issue 212) by Trevor

Cooper:-

Royal wedding at Ipswich, 1297

In the year of a royal wedding [2018], it is appropriate to remember an

earlier royal wedding which took place in Ipswich, 721 years ago.

However, Ipswich was not an obvious place for a royal wedding; there is

a shortage of information and disagreement over the actual date and

location in the town.

On 8 January 1297, Elizabeth of Rhuddlan, the daughter of King Edward I

and Eleanor of Castile, married John, Count of Holland at St Peter and

St Paul’s church, Ipswich, now known as St

Peter’s by the Waterfront. In attendance at the marriage were

Elizabeth's sister Margaret, her father, Edward I King of England, and

her brother Edward, (later King Edward II). Queen Eleanor was already

dead. The great nobles of the land and the low countries would also

have been in attendance.

There is a rival claim to the location of the wedding: the now

demolished Chapel of Our Lady, which until

the reformation was a chapel on the corner of St Matthews Street and

Lady Lane. It was a major site for pilgrimage; its attraction was the

miraculous healing powers of the statue of The Virgin Mary. It is

likely that the actual wedding took place in the larger church of St

Peter, but that the royal party made a devotional visit to the Chapel

of Our Lady as part of the overall wedding proceedings.

Elizabeth was 15 when she married, and her husband was 13. The marriage

with Count John was dynastic and political. Holland had close trade

links with England. They were betrothed when John was only 1. As part

of the agreement, John was raised in England at Edward’s court;

effectively a hostage for his father’s continued allegiance.

The context for this wedding was a complex proxy military and trade war

between England and France, involving Holland and Flanders. The essence

of the conflict was substantially about Edward’s control of Gascony,

which was the remaining province of England’s possessions in France,

and his assertion of control over Scotland. In both areas Edward was

being challenged by France. It was a great power conflict between

England and France, which drew in the Low Countries, because it was

also about control of the wool trade. Wool was England’s main export

and the greatest source of tax revenue.

By the time of the marriage, John’s father Floris V Count of Holland,

had been murdered in a botched kidnap attempt in 1296, because he had

changed allegiance in favour of France. Edward I was implicated, but it

is unclear how much he was actually involved. Edward condoned the

murder as it suited his purposes: he now had the successor, John Count

of Holland, in his power.

The marriage between Elizabeth and John would have become very urgent

and was brought forward to immediately after the Christmas feast.

Edward would have been keen to establish his control over Holland

through John who would become his son-in-law, to stabilise the

all-important wool trade, and secure the alliances against France. King

Edward invited a number of nobles from Flanders with English

sympathies, to witness the wedding and the king’s power in the Low

Countries. After the wedding John of Renesse (one of these lords) was

appointed regent by Edward I, on behalf of John count of Holland who

was a minor.

St Peter’s in Ipswich would have been chosen as the location for the

wedding for symbolic reasons. In medieval times Ipswich was an

important trading town and port it was crucial to the economic and

political power of the country. In particular it was the major cloth

and wool exporting port for England. The wool trade was an important

source of royal revenues through taxes on exports. Edward probably

chose Ipswich to demonstrate his power over the wool trade to the

French, his own people, and his allies.

It was an Augustinian Priory of St Peter and St Paul which occupied a

six-acre site. As a large priory, it would have had the necessary

buildings to accommodate the king and his retinue. Much of the town

would have been taken over for the lodgings of other notables and all

the attendant clerks, servants, soldiers, priests and others, as

guests or functionaries.

Importantly for this event was that it was easily accessible by sea. It

is likely that the king, his retinue and the bride and groom travelled

by sea; it being quicker and easier than by road. The royal ships would

have been able to moor very close to the priory, where College Street

and Key Street are now, which would have been the original quay. The

foreign guests from Holland and Flanders would have found it

conveniently accessible by sea. It is of course also possible that the

king travelled by road from London after the Christmas feast. It is

likely that much of the king’s baggage and retinue travelled by road

and arrived ahead of the wedding to prepare the accommodation at the

priory, and to finalise the arrangements for the wedding. The royal

baggage train would have brought everything for the king’s comfort;

furniture, the king’s bed, tapestries for wall hangings, plate, clothes

jewellery.

After the wedding John, Count of Holland, was sent to Holland to

establish his authority as ruler, although he was made to promise to

heed the council of Edward’s Regent: he was effectively under the power

of Edward I. Elizabeth was expected to go to Holland with her husband,

but did not wish to go, or Edward I did not want her to go; it is not

clear.

Elizabeth did join her husband in Holland in 1298. Edward I travelled

with her, through the Low Countries with her two sisters Margaret and

Eleanor. This can readily be seen as a royal progress with Edward

demonstrating the extent and reach of his power. They remained for

several months and celebrated Christmas there in 1298.

On 10 November 1299, Count John died of dysentery, though there were

rumours of his murder. No children had been born from the marriage. His

usefulness to Edward had been served. Edward had negotiated a peace

treaty with France. To seal that, Edward himself married again to

Margaret, the half-sister of Philip IV, King of France.

Elizabeth is only connected with Suffolk through this marriage. She was

born at Rhuddlan, north Wales in 1282, and died in childbirth, in 1316,

and was buried at Walden Abbey, Essex. She was born in north Wales

because Edward was at war with the Welsh rulers of Gwynedd, and Eleanor

of Castile his wife was accompanying him as she always did.

But for all this, we have a royal wedding which took place in Ipswich

for strategic reasons: these explain its choice for a royal wedding.

When Elizabeth married her second husband, Humphrey de Bohun, earl of

Hereford in 1302 it was at Westminster Abbey.

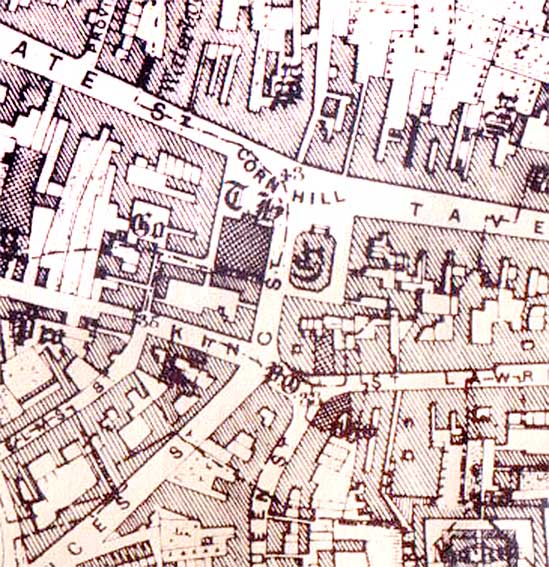

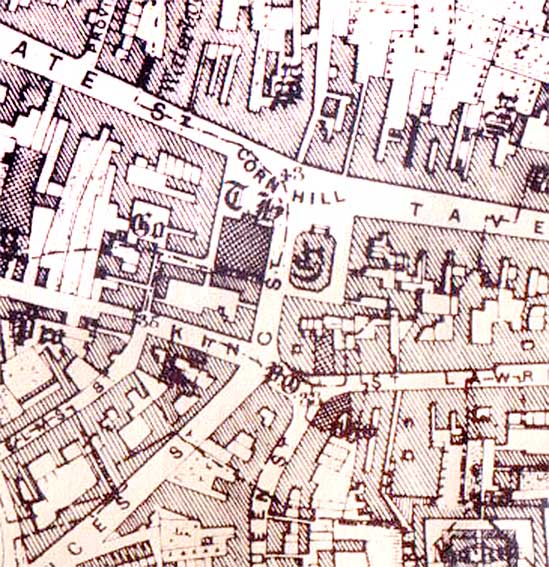

1867 map

1867 map

Edward White's map of Ipswich, 1867 shows

the same area with some notable changes. The block of "The King's Head"

of 1778 is now fragmented into thre separated blocks and we know that

the Sickle stood on the lower right corner, so the King's Head would

appear to have occupied only the upper right building – directly behind

the Town Hall: an indication of a business in decline. The building

east of the Town Hall shown here (the legend is 'Cx') is the first Corn

Exchange awaiting demolition around 1880. The grand Post Office

building we see today was opened in 1882 on the footprint of the

demolished 1810 Corn Exchange. On the map we sees a post office (marked

'PO') at the end of Butter Market, facing the top of Queen Street.

Street names have changed by 1867 and King Street now goes eastwards

from the Arcade (and end of Elm Street) and turns north up to the

Cornhill. Butter Market, as shown on the 1778 map, is here labelled St

Lawrence Street.

[UPDATE

2008/2009: the Corn Exchange was clad in a

work of art. This took the form of a sunny cornfield against a blue sky

printed on plastic sheeting covering the scaffolding. Sadly, this meant

yet another coat of masonry paint, finally killing off some of the King

Street lettering.]

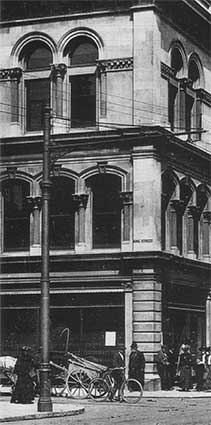

Close-up, 1910

at right

Close-up, 1910

at right

Above: the junction of Princes Street with King Street to the

left. The painted, drop-shadow capitals are clearly shown above the

cornice in a view of the Corn Exchange's corner c.1910. For another

example of a street name painted on the Town Hall stone see 'Lion

Street' below.

Lion Street

2015 images

2015 images

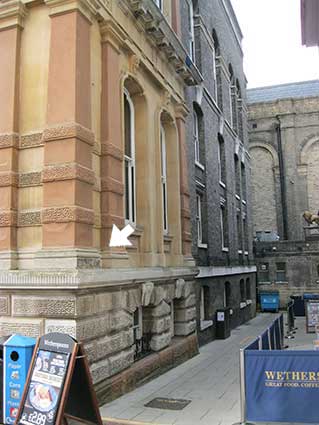

The west end of King Street today is the confluence of three streets:

Elm, Arcade and Lion. The photograph of the arch above shows all three

street nameplates, plus the Ipswich Society blue

plaque for Jean Ingelow.

While many Ipswichians might think of the lane beside the Town Hall

which comes out in King Street as "Golden Lion Passage", it is actually:

'LION STREET.'

and this tiny,

bendy alley is signed four

times.

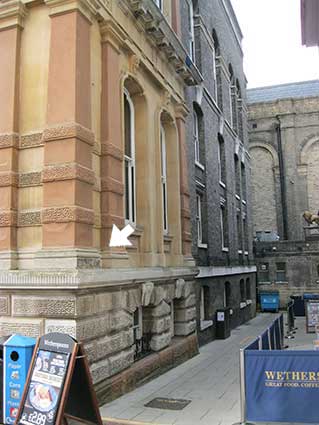

In 2015 we finally noticed the black

capitals, complete with square full stop, spelling out the street name

painted at the base of the square pilaster of the Town Hall (arrowed in

the above photograph). Praise be that the contractors working on the

cleaning of the building's fabric left this tiny detail intact.

Because today's Town Hall was built on the site of the Moot Hall,

itself an adaptation of the Church Of St Mildred (built around AD700,

so Anglo-Saxon in origin), this little lane was once known as 'St

Mildreds Lane'. As we find from the CAMRA information about The Golden

Lion, elsewhere on this page, it was later known as 'Town Hall Passage', presumably post-1868, when the present

building was opened. The only query is that perhaps this latter name

was applied to the narrow passage which used to run behind an earlier

Town Hall on this site linking Golden Lion Yard with the Thoroughfare.

Lion Street is named at each end by the modern street nameplates

bearing serif'd capitals on a dark brown background. Left: the wall of

the Golden Lion Hotel, now a noodle restaurant. Right: the corner with

King

Street; this nameplate has the addition of a full stop.

Public lavatories at the Corn Exchange

[UPDATE 22.6.2016: 'The sign "Lion Street" on the

rounded

corner with King Street in the right-hand picture – arched doorway and

window with iron bars – it used to be the most wonderful

Victorian-style public loo! As a child in the 1950s I would ask to go

in there at every visit to town because it was so pretty – lovely

tiles, shiny brasswork, I would spend far too long in there, I loved

it! My father was not so happy with it as he had to wait for me

outside for long stretches. I have often wondered what happened to it.

I have long imagined it to still be there behind the scenes, awaiting

rediscovery, though probably not, knowing the Council. Yes, [there was]

an underground Gents loo: the railings along Lion Street, on the back

of the old Corn Exchange, look over and down, all still there! There

was

often a very bad-tempered loo-attendant in the Ladies, she would watch

me with deep suspicion!

I am a Collings from Norfolk & Suffolk. In King Street, the old

Sickle Inn was kept by my Great Grandfather's cousin, Nathaniel Sterry

in the 1860s; he died there in 1869. My Great Grandfather, George

Sterry, kept The Blooming Fuchsia, The

Sorrell Horse, and beer-houses in

Alan Road. My Granny, Grace Collings, née Sterry, kept The Three Tuns

in Commercial Road, and the Kings Head in East

Bergholt. I was

especially interested in your pages on Alan

Road and Rosehill Road as

that is where these folk purchased houses. My father, Alan Collings,

was born at 119 Rosehill Road, one of his grandparents’ houses; it's

probably how he got his name***! My Collings Great Grandparents

purchased

one of the small holdings on Foxhall Road: 2 Lincoln Villas; they ran a

market garden, it is gone now sadly. They were the parents to P.

Collings, grocers at Whitton and Castle Hill shops. So, your website

has been very interesting to me. Your website is EXCELLENT! Thank you.

Lin Jensen.' Many thanks to Lin for

this memory – does anyone else recall the Victorian public toilets on

this corner of the Corn Exchange?]

*** See our Street name derivations

page for 'Alan Road'.

See the period photograph of the Moy Coal Office Arcade below for

conclusive proof about the toilets.

2016 images

2016 images

Above left: the corner entrance which used to be the Ladies public

convenience (taken from under 'The Arcade'); above right: those

railings

around the basement space of the Corn Exchange in Lion Street.

An interesting swing-winch in cast iron is still situated behind the

railings, presumably once used to load supplies for the Corn Exchange from the lane and

down into the area below. Right: the locked gate which would have

enabled access to the underground Gentlemen's public convenience – it's

quite a long way down those narrow steps. Below: let's not forget to

look up at this elevation of the building. Away from the stone-faced

frontage on King Street is a rather simple, attractive combination of

white and pink brick details with romanesque arches and

circular/half-circular windows. This is seldom noticed by passers-by in

the narrow Lion Street.

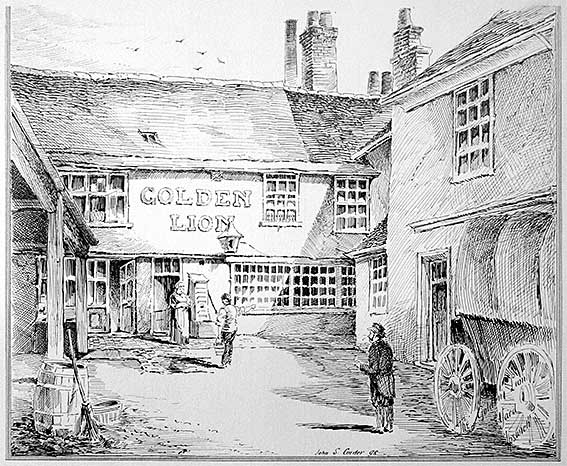

Golden Lion Yard

1898

image

1898

image

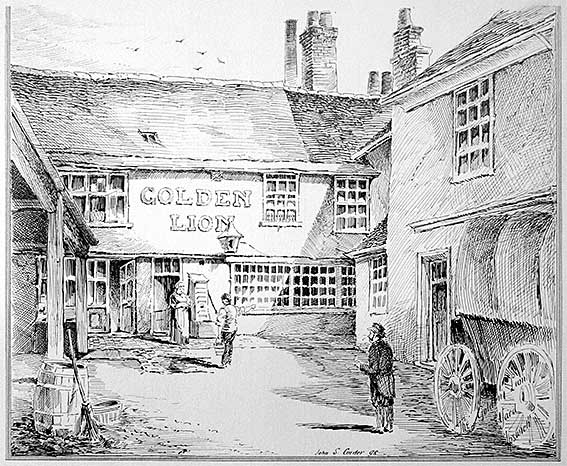

John Shewell Corder appears elsewhere in this website: building

historian, architect and illustrator of Ipswich, also son of Frederick

Corder whose department store ran between Tavern Street and Butter

Market (today's Waterstone's shop). His 1898 illustration shows the

coaching entrance of The Golden Lion, from Golden Lion Yard. The 2021

photograph shows it in a sorry state, definitely the 'back yard' of the

hotel with intrusive metal fire escape, relying on its hotel entrance

on Lion Street/Cornhill (see

below).

2021

images

2021

images

It is notable on Pennington's 1778 map, a detail of which is

shown on our King Street page, that Elm

Street appears to run up to Golden Lion Yard. One assumes that this

would be the access for post coaches. The legend 'Golden Lion' appears

on the map actually in the yard, rather than on Cornhill. Below: the

limesone setts are in largely good condition. Compare with Coytes Gardens.

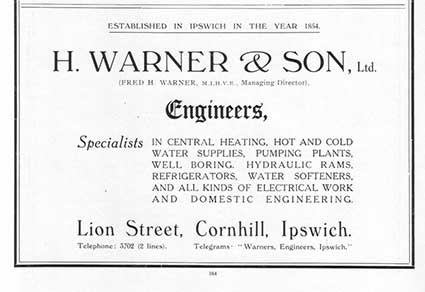

8 Lion Street

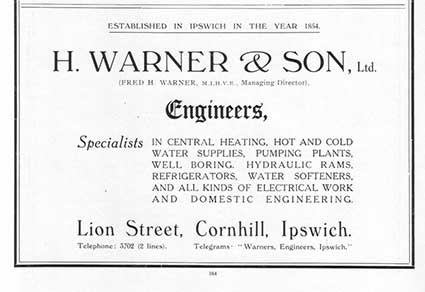

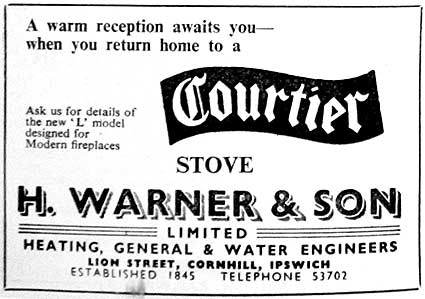

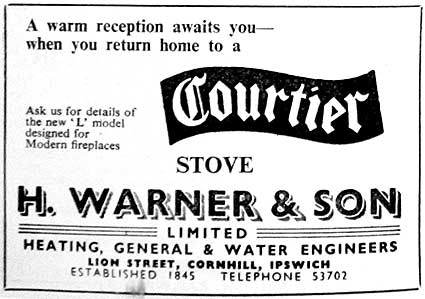

Below: a somewhat surprising advertisement from

1936 promoting a

plumbing company with premises in the relatively tiny Lion Street. H.

Warner & Son

Ltd. were based in the Grade II Listed, 17th century building at 8 Lion

Street; today it is a restaurant (in 2023 The Moloko) just north of the

arcade. The company adjusts the date at which it was founded from 1854

to 1845 in the 1963 advert – or it could be a typo? One online resource

states that there are company records from 1859 to 2004.

1936

advertisement

1936

advertisement  1963 advertisement

1963 advertisement

See our Street furniture

page for a ground-level casting by the company.

Below: a 2019 view of the former premises of H. Warner & Son

Ltd. which stood opposite the Borough's public lavatories – perhaps

appropriate for a plumbing company. Golden Lion Yard is visible in the

background.

2019 image of 8 Lion Street

2019 image of 8 Lion Street

The Cornhill frontage

The large sculpture of a lion on the rooftop stands over the main door

into the

hotel. In 1960 a photograph shows three windows to the right (Suffolk

CAMRA website, see Links). These days a

restaurant is accessible by an additional entrance, but the interior

lobby of the hotel can still be identified. Also from CAMRA:

'Originally called the White Lion, the name changed during the 1570s.

According to Alfred Hedges' book Inns

and Inn Signs of Norfolk and Suffolk (1976), the inn here dates

from about 1400.' This building is Listed Grade II and a former posting house, located in one corner

of

the historic Cornhill. Once it stood

beside the moot hall, today it is

dwarfed by the Victorian Town Hall. Originally the whole hotel complex

formed the Golden Lion as the large roof sign suggests. The lion statue

was once gilded; small remnants of this gilding still remain. The small

public house called The Golden Lion with its entrance in Lion Street

was open until 2019. CAMRA adds: 'The Golden Lion Tap was listed

separately from the Golden Lion in the 1861 census. The 1916 Kelly's

Directory lists the Lion Hotel Vaults in Town Hall Passage (no

further

information), which may refer to this establishment.'

2021 images

2021 images

Above (from left): the Town Hall western

corner, the blue

painted Golden Lion pub, the Golden Lion hotel, the noodle restaurant,

Mannings pub and the southern part of Grimwade's store.

The golden lion atop the building certainly appears to have been

repainted at some point and doesn't look at all bad.

Looking down Lion Street, we see the former Wetherspoon's public house

featuring a small golden lion – presumably put there by that company

with the pub name beneath, The boarded-up window has the name 'THE

GOLDEN LION' painted over above.

Arcade Street

2016 images

2016 images

Above: on the other side of the Arcade (which is more correctly an

extended arch, or a short tunnel). At the west end of Arcade Street is

a pressed metal nameplate attached to a curving Suffolk white brick

wall, which is in need of some repair. This particular building has the

distinction of playing host in the story of the struggle for women's

suffrage. It used to be the office of the Ipswich branch of the Women's

Freedom League. It was here that the suffragette and tax resister,

Constance Andrews, was feted following her release from Ipswich Gaol in

St Helens Street after refusing to pay her dog licence.

'The Mansion'

Before the street was cut through, the building was a town house

known as Don Read's Mansion; it marked the end of King Street. John

Norman in one of his informative Ipswich

icons columns in the local press (Lives lived in the shadow of our town hall

21.1.2018) writes:

'The mansion was bought by the East of England Bank in 1836, who

installed William Ingelow as banker. It was an extensive six-bedroomed

property with a 20-foot-square banking hall and a similar-sized dining

room. His family lived there and an Ipswich Society blue plaque

commemorates daughter Jean, a poetess. In 1845 the East of England Bank

failed and in 1848 the house was extensively remodelled, with an arch

being cut through into a new street. This ran to the corner where the

new museum was being constructed and then up to Westgate Street.'

2021 image

2021 image

Here is the view from King Street with Elm

Street to the left and Lion Street to the right. Horse-drawn

coaches would have approached the Golden Lion coaching yard from here.

Early

20th century photograph?

Early

20th century photograph?

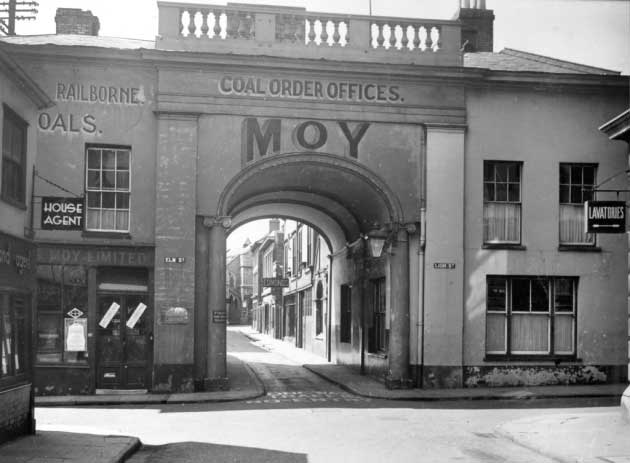

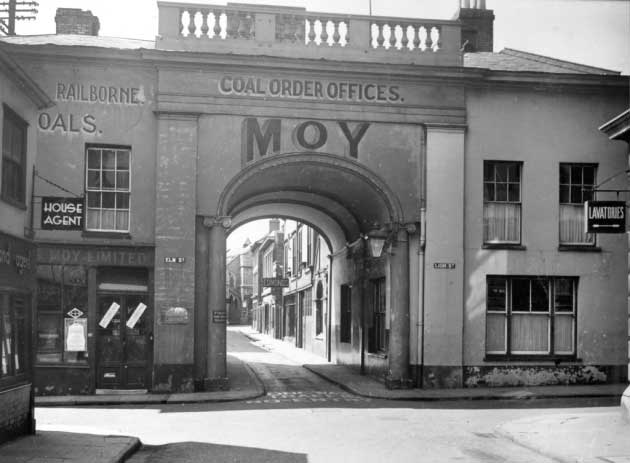

This above photograph was taken by William Lovell (who was the chief

librarian with the East Anglian Daily Times Company for several

decades) via the excellent David Kindred column Days gone by. The revelation

that the 'arcade' at this point was used as a billboard for the coal

company is surprising and one wonders if the lettering still lies

beneath today's layers of masonry paint. It looks as if the signwriter

has executed his work on the cement render of the remodelled building.

'... RAILBORNE.

... [C]OALS.

COAL ORDER

OFFICES.

MOY'

The capitals all bear a drop-shadow with the huge 'MOY'

varying in size to closely follow the curve of the arch. The

reversed-out street nameplates ('ELM ST. AND LION ST.)

on either side of the arch are a bonus – today they have modern

replacements in the same positions – as is the hanging 'LAVATORIES'

(probably a lit glass sign?) on the corner with Lion Street, proving

conclusively that

the Borough provided public toilet facilities here (see above). Not

something that can oft

be said today...

The shop sign at the left reads: '... MOY LIMITED'

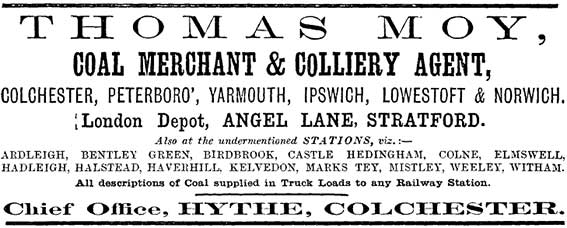

1870s

advertisement

1870s

advertisement

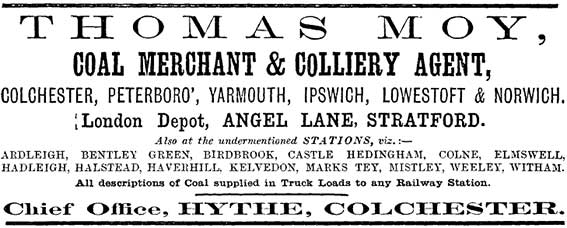

Moy was by far the biggest coal merchant in

East Anglia. At Derby Road railway station in

east Ipswich there were sidings on either side of the line. These were

mainly used by coal merchants: Rowland Manthorpe, E. A. Stow and Thomas

Moy Ltd, amongst others.

Thomas Moy stabled their horses in the yard and for many years this was

still the most common means of delivering coal to households.

Incidentally, the curious word 'RAILBORNE' seen to the upper left

refers to coal brought by rail, as opposed to 'sea coal', brought by

ship. It appears that 'rail-borne' was conflated into a kind of brand

name.

[UPDATE 29.5.2023: spotted on

Facebook, a William Vick photograph taken c.1890 (not shown here) of the same scene. The upper,

horizontal lettering reads in capitals 'JAMES

HARRISON & SON.' and running all the way around the arch in

condensed capitals: 'MANUFACTURING

CABINET-MAKERS.' – all with drop-shadow. Incidentally, the

corner property at left at this time was a public house: The Hermit was

situated at 7-11 King Street and closed in 1922; it has since had a

variety of uses as an estate agents and coffee bar.]

The original function of the opening here – Arcade Street having been

built as an escape from Museum Street before the latter was extended to

meet Elm Street – is shown by the narrow vehicle access, made narrower

by a pedestrian pavement on each side. On the tarmac, to be read from

the King Street side, are the white letters: 'ONE WAY TRAFFIC, NO

ENTRY' (just readable in the photograph).

2023 image

courtesy Sandy Phillips

2023 image

courtesy Sandy Phillips

'ARCADE

[STREET] TAVERN'

Sandy Phillips was cycling towards the arch in April

2023 when she noticed and photographed the lettering painted on the

rendered and blue-washed surface above. Quite a long ladder (or

scaffolding tower) would have been required by the signwriter, we

think. Or it may have been applied to the uneven surface as a vinyl.

The small caps of the word 'STREET' are turned through 90 degrees and

bracketed by two vertical rules in the centre. This is an excellent

view directly down Arcade Street with part of the Museum Street Methodist Chapel frontage

visible at the end.

2018 images

2018 images

There are some interesting buildings in Arcade Street, often

overlooked, perhaps. Passing through the arch, and opposite the beer

garden of the bar fronting Elm Street (once the Moy coal office), there

is the building shown above at 2 Arcade Street. At the time of writing

2 to 6 Arcade Street is occupied by Blocks Solicitors. This

perfectly-formed little white brick building features ball finials over

the rather good carved supports, one of which is shown above. The

window with its decorative arch is pleasing. It must date from the

1840s to 1850s when Museum Street and Arcade Street were cut through

(see below).

Further down the street, past the modern Ipswich County Court – the

faded royal coat of arms appears on our Blue

plaques page – stands the long-empty hall which was opened as the

Scout Headquarters in April 1964. Its Art Deco frontage resembles a

cinema and attempts to convert the building into a bar and restaurant

have come and gone. Dated rain-hoppers

can be seen on the other side of the road.

Arcade Street and Museum Street are

full of sizeable Victorian houses. As the professional businesses which

have occupied these premises for fifty years move out, the buildings

are set to return to residential use.

Street evolution

When Joseph Pennington made his map of Ipswich in the 1770s, the area

between Westgate Street and Elm Street was entirely taken up with

gardens, but in the 1840s plans were made for a new street linking

Westgate and Elm streets. An opening for the new thoroughfare was made

through part of what had been Seckford House. Thomas Seckford

(1515-1587) built his mansion at this site, sometimes known as 'the

Great Place' or 'the Great House', such was its prestige. See our Lost Ipswich signs page for the 'Before

Willis' section: more on the streets in this area and an engraving of

the impressive Seckford House. The new street ran south as far as the

new Ipswich Museum, designed by Christopher Fleury opened in 1847.

Today this is Arlington's Restaurant. The street hugged the Museum,

taking a sharp left turn and heading eastwards. However, it did not

connect with the Lion/King/Elm Street junction until 1850 with the

cutting of the 'Arcade' through one of the houses (lived in between

1834-1844 by novelist Jean Ingelow – see our Blue

plaques page). In 1856 Thursby's Lane (up to then linking Friars

Street northwards to Elm Street) was

extended to a junction with Museum

Street. The east-west part of Museum Street was then renamed Arcade

Street and the whole north-south street from Westgate Street to Princes

Street – including the kink at the Arcade Street junction which we

see

today – was renamed Museum Street. The tiny stub of Thursby's Lane

between Princes Street and Friars Street stayed until the building of

the Willis building in 1975, when roads were reshaped or lost.

[Information from R. Malster: Wharncliffe

companion, see Reading list.]

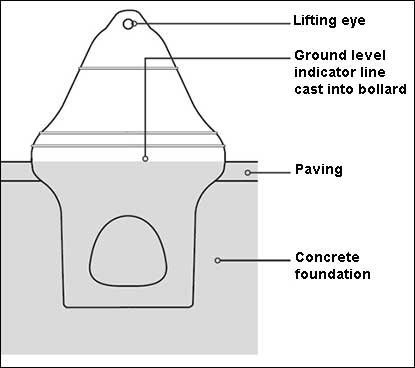

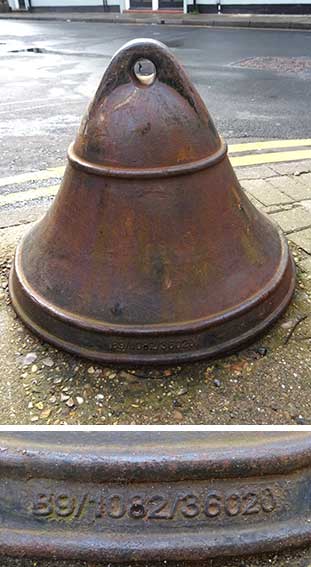

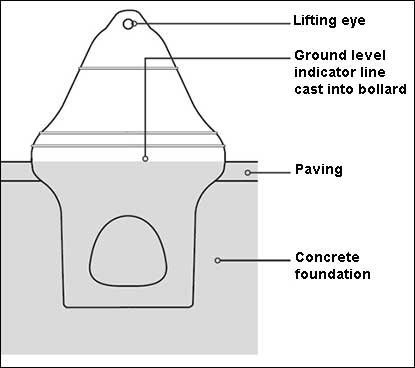

Bell bollard

2023

images courtesy Sandy

Phillips

2023

images courtesy Sandy

Phillips

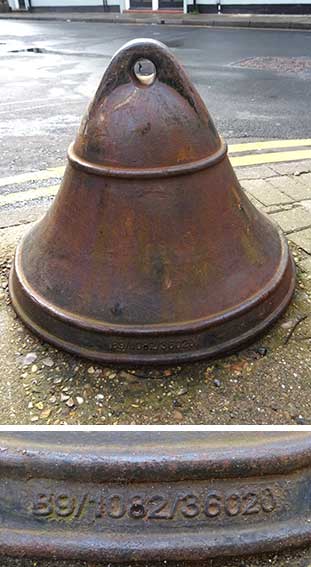

Above: 'Walking down Arcade Street this morning [March

2023], past the arch towards Museum Street, I spotted this Bell, no

manufacturer name that I could see. Sandy Phillips.' Thanks to Sandy

for adding to her contributions of images of drain and other

ground-level castings (see also our Cocksedge

page). These 'bell bollards' by a company called Furnitubes and are

there to protect pedestrians and buildings from heavy goods vehicles.

If heavy vehicle was to begin mounting the pavement the wheels of

the vehicle would be deflected away from the pathway and back onto the

road. Note in the diagram the amount of the casting buried underground.

Another bell bollard can be seen in St Stephens Lane, outside Doug

Atfield's The Sun Inn. We hear that Doug

installed the bollard to protect his fine 15th/16th century building

from heavy

lorries delivering goods to the rear of stores in Upper Brook Street

(then C&A and Sainsburys), to the dipleasure of the authorities.

It's still there.

See also our Street furniture page

which draws together links to other bollards on the websit;, included

there is a 2023 photograph of a rectangular variation on the bell

bollard.

Below: 'Past the bell bollard, towards Museum

Street,

there is a drain each side of the road: G. H. Laud & Son, not an

Ipswich Co. Sandy Phillips'. G. H. Laud &

Son were a

Liverpool foundry.

Related pages

Our Cornhill1 and Cornhill 2 pages feature notable dates

in its history and a more detailed survey of the changes over time,

including King Street.

See our Museum Street

page for 1778 and 1902 comparative maps including this location.

Crown & Anchor / Westgate Street

Lady Lane,

Civic Drive

Salem Church / St

Georges Street

Princes

Street

Friars Bridge Road

Coytes Gardens

Museum Street

Methodist Church

Black Horse Lane

Ipswich

Museum

Street nameplates

Historic maps

Street index

Street name derivations

Home

Please email any comments and contributions by clicking here.

Search Ipswich

Historic Lettering

©2004 Copyright

throughout the Ipswich

Historic Lettering site: Borin Van Loon

No reproduction of text or images without express written permission

2001

images

2001

images 2001

images

2001

images Lower

example is Arcade St end (includes full stop)

Lower

example is Arcade St end (includes full stop)

1778 map

1778 map 1867 map

1867 map

Close-up, 1910

at right

Close-up, 1910

at right

2015 images

2015 images

2016 images

2016 images

1898

image

1898

image 2021

images

2021

images

1936

advertisement

1936

advertisement  1963 advertisement

1963 advertisement 2019 image of 8 Lion Street

2019 image of 8 Lion Street 2021 images

2021 images

2016 images

2016 images 2021 image

2021 image Early

20th century photograph?

Early

20th century photograph? 1870s

advertisement

1870s

advertisement 2023 image

courtesy Sandy Phillips

2023 image

courtesy Sandy Phillips

2018 images

2018 images 2023

images courtesy Sandy

Phillips

2023

images courtesy Sandy

Phillips