St

Mary-at-the-Quay

The

weather-vane and the wrought iron gateway

2014 image

2014 image

Approaching the church of St Mary-at-the-Quay – the middle of

the

three medieval dockland churches – from St

Clement, the weather vane is

still in place, the key

forming the vane at the top. The gold-painted key vane

was in place by the 1670s, but what we see today is a more recent

replacement, albeit with a broken 'N'. The word 'key' is said to be a

version of

the word 'quay', as the church is a matter of yards from the Wet Dock. In

1306 the quay was known as the 'Kay', from its Danish equivalent 'Kaai'

and the Middle English 'Caie'.

2013 images

2013 images

Although there is little noticeable lettering on the fabric of

the

building, the wrought iron gates include a monogram with the key symbol

linking the 'S' and 'M'. In 2013 this is picked out in red paint.

See our Albert Clarke, 'Art Smith'

page for his own photograph of the gates after he had made them.

See our page on Public

clocks in Ipswich for a 2018 view of the church tower and its

clock(s).

The south door is the main entrance to the church and we

understand that in 1876 the door from the old Grammar School was placed

here; presumably it is the one we see today. The plaque above the south

door is almost unreadable, so we include the text here, with its odd

lack of

full stops:

'ST MARY . QUAY .

IPSWICH

This ancient church is maintained by the

REDUNDANT CHURCHES FUND

St. Andrew-by-the-Wardrobe, Queen Victoria St.

London EC1V 5DE with monies provided by Parliament

by the Church of England and by the gifts of the public

Though no longer required for regular worship

it remains consecrated to the service of God

Please respect it accordingly

FOR THE KEY PLEASE SEE

SEPARATE NOTICE'

Built on the site of an earlier place of worship the main period

of construction of St Mary-at-the-Quay was 1443-1543, supported by rich

merchants who lived in the area, notably Henry

Tooley, whose tomb can be found in the north transept. The hammer

beam roof is considered to be second most

important in the county and is a tribute to the timber shipbuilders of

the late medieval period. The roof of the extended chancel of the

nearby St Peter's Church (as used by

the monks

of St Peter & St Paul monastery)

was probably dismantled after the dissolution and re-erected at the

chancel end of St Mary-at-the-Quay. Another candidate might have been

the

refectory of the monastery, but St Peter's Church is most likely.

The tower used to have a 17th century lead cupola on top which

housed the bell connected to the newly-installed clock. This was still

visible in the 1950s. The roof and interior are in a

sorry state, a concrete floor and parquet layer caused the inherent

dampness of this formerly marshy ground to migrate to the walls and

cause rendering and plaster to crumble. The stone pillars have acted as

wicks to draw up the contaminated water and attack the limestone quite

dramatically. The planned refurbishment in 2013 by a charity, will save

the church from steady decline.

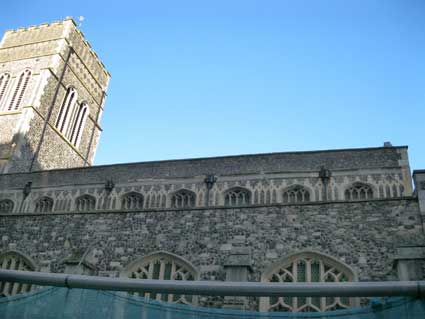

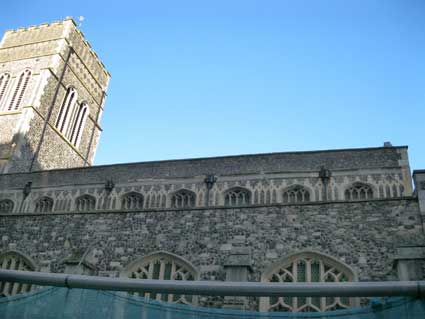

The rainhoppers

Southern

elevation

Southern

elevation

The nave, transepts and chancel are capped by parapets, the south nave

parapet still retaining the light coloured gault bricks with which it

was restored in the 18th or early 19th century. Of special note are the

hopper-heads above the downpipes which drain the rainwater from the

nave roof. These have little cartouche decorations with initials

(possibly of the churchwardens: 'NA' and

'CS' alternately) and the date

'1741'. Such pieces of 18th

century

metalwork are a rare survival.

And in 2015, following refurbishment...

NA, 1741 ... CS,

1741 ... NA, 1741

... CS, 1741

For

other examples of dated hopper-heads, see our Plaques

page (The Walk), Gatacre Road School, Tooley's Almshouses and Arcade Street (dated buildings examples).

Northern elevation

Northern elevation

It looks as though one of the hopper-heads on the northern side

reads: 'NA', '1900'.

Archaeology

[UPDATE 14.2.2014: St

Mary-at-the-Quay Church in the pouring rain. Prior to its conversion

into a ‘Wellbeing Heritage Centre’ by Suffolk MIND and partners an

archaeological dig is underway, due to finish in April 2014. The open

day coincided with a full peal of the church’s bells lasting over two

hours. The ringers were probably the only warm people in the church,

but there was plenty to see in the extraordinary exposed burials,

accessed through the small priest’s doorway at the side of the chancel,

a table of finds and a child’s skeleton laid out on Henry Tooley’s

tomb. Des Pawson’s (see Links) rope-making

display drew attention to the maritime nature of the church – the clue

is in the title – which originally stood close to the early dockside.

It was built on the site of a previous church over the hundred years

from 1443. As their work progresses, who knows what the archaeologists

will find further down at Anglo-Saxon or even earlier layers?]

2014 images

2014 images

Intact, fully-articulated skeletons have been exposed, including the

surprisingly tall individual shown above. However, previous burials in

the very small remaining graveyard have been disturbed in sinking new

graves and brick-built tombs, so the jumbled remnants were thrown into

a charnel pit (below): a rather disturbing mass of the remnants of

humanity. On a board on the tomb of the noted merchant and benefactor

to the town, Henry Tooley, are laid out

the almost complete bones of a child exhumed during the dig.

Below, the finds table with a colourful diplay of ceramic shards from a

variety of eras. Of note is the grey jar lip seen at lower right which

is Ipswich ware. 'Ipswich ware' (Middle Saxon, 700-850 AD) is the name

given to plain sandy greyware which was made in two main fabrics -

smooth and gritty. Vessels were generally small, medium and large jars

with plain upright rims. Hanging vessels with upright pierced lugs were

also made, and there were some rarer forms such as decorated bottles.

Jar bases are characteristically very thick, and upper bodies are often

'girth-grooved' by finger-rilling. The ware is thought to have been

made on a hand-turned 'slow-wheel', as opposed to the fast kick-wheel

used by Roman and Late Saxon potters. Used locally, the pots were also

traded and remains have been found over quite a wide area of the

country.

And, for our historic lettering website, it was good to see several

coins found during the first stages of the dig including this

strikingly-lettered example with a fine use of the indefinite article:

'AN

IPSWICH

FARTHING

1670'

Restoration 2014

2014

images

2014

images

27.3.2014. These photographs

from Star Lane and (below) from College Street/Key

Street from the 27 March 2014 show the huge scaffolding structure under

construction which cover, but does not rest upon the delicate

roof. Within a few weeks the whole was covered in sheeting.

23.5.2014. Here's a fascinating

panorama – probably an unrepeatable view – of Star

Lane, Key Street, the bus depot, the Premier Inn and other Wet

Dock developments

(some completed, some static) and the clock tower of the Custom House

just

visible behind the blue 'Regatta Quay' hoarding. The view is from the

scaffolding surrounding the east wall of St Mary-at-the-Quay during

restoration – the upper platform to the right of the photograph (above

right) – with the camera poked through a slit in the plastic

sheeting: montage of two shots. The only way of getting a better view

would have been to stand atop the St Mary church tower.

May

2014 images

May

2014 images

Meanwhile, inside the church, next to the altar table, a mass of clear

plastic sacks was noticed. They were full of people.

Eye sockets of skulls peer eerily over the tops of the sacks.

Through the tiny priest's door, and we see an updated view of

the archeological dig on the site to be occupied by the new building.

Although there had been heavy rain in early 2014, it became clear that

the charnel pit was flooded due to ground water coming up into the

trenches. Such are the problems faced by those exploring our history in

the soil and proof that St Mary-at-the-Quay was definitely built on

marshy land: the source of many of its structural problems. All

the surrounding springs seem to converge here.

Raching the parts never reached before

Climbing the scaffolding (with permission and safety gear) we viewed

the methods used to examine and repair main roof timbers. That shown

below is being supported by strapping attached to the outer skeleton of

scaffolding. The lower part is currently sitting on fresh air until

sections can be replaced; the adze marks on the upper face of the beam

show the hand-worked finish. The surrounding close-boarding probably

dates to the last, partial refurbishment of the roof in the 1960s. The

flint flushwork integrated into two elaborately-cut stone elements

(note the mason's pencilled 'FACE' lettering indicating the smooth,

dressed outer surface). These are topped off by a greased steel

tie-bar, awaiting its bolt, which runs right across the width of the

church roof to stabilise the structure.

Below: two carved spandrels, in rather good condition, lay on the

scaffolding platform, high up in the roof space.

Carved wooden saints, their faces chopped off by Reformation

puritan zealots, on the uprights of the hammer-beam supports. See

our Church of St Clement page for

information about the 17th century activities of William Dowsing in

destroying 'idolatrous' images and carvings.

Below: the view from the chancel of the scaffolding structure

within the nave and, right, the view across an upper level showing the

position of the carved saints between the clerestory windows.

Below: details of spandrel brackets showing, to the left, the

arrangement of the double hammer beam support for the roof. The

exposed tenons indicate the places where the missing carved angels were

located.

Photographs

courtesy John Norman

Photographs

courtesy John Norman

A selection of smaller images of St Mary-at-the-Quay during

restoration, May 2014.

|

|

|

|

|

|

An ancient oak beam displays insect damage.

|

|

Half-round rods with sand-cast lead sheeting laying on

boards.

|

|

Knapped flints and mortar in situ.

|

Flints and masonry: work in progress.

|

Nearing completion 2016

2016 images

2016 images

Above: the return of the wrought iron 'S', 'M' and key motif above the

resored gates with the new wing in the background.

A newly-placed plaque near to the south door in stainless steel (the

old circular plaque shown at the top of this page is still in place)

interestingly names the church 'St Mary, Ipswich'. Give that there are

three other Marion churches in Ipswich (St Mary-at-Elms, St

Mary-Le-Tower, St Mary Stoke), This church really ought be given its

correct name: 'St Mary-at-the Key' by The Churches Conservation Trust.

Also, above right, the restored and cleaned west door, the spandrel

shields are particularly striking.

Grand Opening, October 2016

2016 images

2016 images

Below: one of the finest double hammerbeam church roofs in Suffolk

(possibly second only to the church at Needham

Market),

post-restoration.

The simple table altar partially obscures the ceramic tile lettering on

the decorative east wall. Below (the second panel damaged):

'I am the

Lilly of the

Valleys'

'I am the

Rose of

Sharon'

2017 images

2017 images

Centrally, in black and red gothic lettering on a gold background:

'This do in Remembrance of ME'

2016

2016

2017 images

2017 images

The close-ups reveal that this lettering is painted onto a boards,

which are fixed to the wall.

The churchyard dig unearthed these metal coffin plates, the lettering

engraved on them still remarkably readable:

'CHARLES JOBSON

DIED

23rd Augst.

1832,

aged 59 years'

'ANN JOBSON

DIED

30

th Aug

st.

30th Augst.'

Researchers on the restoration

project have found some fascinating information about Mr Jobson and his

life:-

Charles Jobson was born c.1773 in

Ipswich. We know from a record of Freemen of Ipswich that his father

was William Jobson. Charles married Ann Ramsey at St Mary-at-the-Quay

Church on 29 May 1796; both signed their names with an ‘X’. Charles’

father was buried at St Mary-at-the-Quay on 8 March 1809 (the document

is held at Suffolk Record Office).

- Charles had a son, also named

Charles, who married Mary wade from St Mary-at-Stoke parish in 1821.

Charles junior, a Mariner like his father and two generations of male

ancestors before him, also became a Freeman in 1819.

- His daughter, Mary Ann married

James Trott in 1823 who was Master of the brig Union at Woodbridge.

- His daughter, Caroline,

married John Bush in 1828.

- His daughter, Charlotte,

married John Randall in 1829.

On 30 August 1831 Charles’ wife Ann

died at the age of 56 and was buried at St Mary-at-the-Quay. On 12 June

1832 Charles married Jemima Hamblin, a widow of the parish of St Peter.

Jemima carried on Charles’ business at the Smack Inn after his death.

Charles died on 28 August 1832, aged 59 (just two-and-a-half months

since his remarriage), and was buried in the tomb where he was found in

2014 in the graveyard of St Mary-at-the-Quay.

Old bottles dating from 1872 to 1956 found in tomb backfill in the

churchyard excavations. For information about Talbot's mineral waters

which were sold in some of the examples shown here , see our page about

The Unicorn.

The font has been relocated to a space next to the north door (which is

used as the main entrance), protected by a glass screen.

By early 2018 the gold lettering is in place on the curving wall by the

south door...

'QUAY PLACE'

2018 images

2018 images

... matching the gold monogram in wrought iron with the church tower in

the background.

And the view of old and new from the east.

2018 image

2018 image

See our page on The Mill for some 2008

views of Cranfields Flour Mills and the Winerack from inside St

Mary-at-the-Quay.

Home

Please email any comments and contributions by clicking here.

Search Ipswich

Historic Lettering

©2004 Copyright

throughout the Ipswich

Historic Lettering site: Borin Van Loon

No reproduction of text or images without express written permission

2014 image

2014 image 2013 images

2013 images

Southern

elevation

Southern

elevation

Northern elevation

Northern elevation

2014 images

2014 images

2014

images

2014

images

May

2014 images

May

2014 images

Photographs

courtesy John Norman

Photographs

courtesy John Norman

2016 images

2016 images

2016 images

2016 images

2017 images

2017 images 2016

2016 2017 images

2017 images

2018 images

2018 images

2018 image

2018 image