Norwich

Long missing from the Ipswich Historic Lettering website, almost

all of these photographs were taken on a single walk around the city

centre in the June 2013. The massive task of building the page and

researching the examples was finally completed six years later. It does

not seek to be comprehensive, but to illustrate the huge variety of

historic lettering visible in the city.

Needless to say, this page represents a time capsule and some changes

have occurred in the intervening years.

Norwich is the county town of Norfolk, situated on the River

Wensum. From the Middle Ages until the Industrial Revolution, Norwich

was the largest city in England after London, and one of the most

important. Norwich is the most complete medieval city in Britain

and it has notable cathedral. The fabric of the city centre is rich in

historic

lettering, including enticing street nameplates.

2013 images

2013 images

2 Recorder Road. Corner

with 120 Prince of Wales Road (the Compleat Angler pub); note the

uncomforatble closeness of the twobuildings. ‘New Patrick’s

Yard’: ‘1912’ is the date on the gable end (not seen by us). The

decorative

brickwork entrance has the monogram ‘OSLJ’ (not necessarily in that

order) in

its terra cotta keystone with two matching tablets on each side of the

door showing trees.

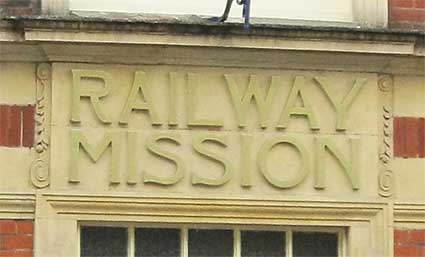

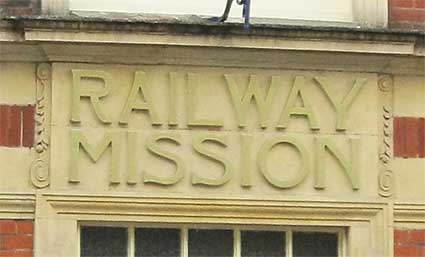

79 Prince of Wales Road.

'RAILWAY MISSION' in large, relief capitals above the

central

door is part of a well-preserved building, with a fine Art Nouveau

facade It is still

in use as the Prince of Wales Road Evangelical Church.

As with most East Anglian towns and cities, the railway station in

Norwich was built outside of the immediate centre because its main use

was not for passengers, but for goods, especially livestock, which

needed space to be penned nearby until the time for their journey

began. There was another station on a different line closer to the city

centre, but it is Thorpe station that has survived. As in Cambridge and

Ipswich, where the main stations were similarly placed for the same

reason, the area became home to dozens of rows of terraced houses, for

workers on the railway and in the industries that the presence of the

line generated. Although the Church of England was not slow to respond

to what it saw as the pastoral needs of these workers, there were

plenty of other denominations elbowing for their attention. For a

start, many incomers were Catholics, and it was in the 19th century

that the Catholic population of the city ballooned. But it was also the

time that the congregational chapels took off, and although many of

them have fallen prey to demolition in recent decades, there are some

interesting survivals, including this little Railway Mission chapel of

the 1890s. Prince of Wales Road, like Princes

Street in Ipswich, was

built specifically to connect the railway station with the heart of the

town, and still today this chapel is a familiar sight for pedestrians

en route between one and the

other. Happily, it is still in use for its

original purpose; as the Prince of Wales Road Evangelical Church, it

maintains two services every Sunday. [Information

from Simon Knott's Norfolk Churches website (see Links).]

(The Railway Mission still exists as a national organisation – not

now connected to this building.)

60-62 Prince of Wales Road.

Night club and Hotel Belmonte. Decorative mouldings on pilasters at

hotel entrance with the hotel name frosted into the glass door.

Above the shop-front: large, bulging, three-dimensional scrolling,

tiled

panels bearing ‘No 62’ and ‘No 60’. A sneaky use of the superior 'o'

inside the top of the 'N'.

Hardwick House, Agricultural

Hall Plain. A grand neo-classical stone building; former ‘POST

OFFICE.’ (carved into the pediment in relief capitals below an

elaborate crown with swags of flowers in stone). Hardwick House was

designed by Philip Hardwick and it opened in January 1866 as Harvey and

Hudson’s Crown Bank, later taken over by the Post Office which was

there for almost a century. Savills has been operating in Norwich since

1950 and moved out of the building in 2018. Parts are residential.

‘BANK PLAIN’ street nameplate

on railings outside former bank building by E. Boardman & Son and

Brierley & Rutherford, 1929 (and extended by Fielden & Mawson

in 1984-85). Red brick with Portland stone detailing (Listed Grade II).

Barclays Bank has left and it is now a conference and event venue

operated by the OPEN Youth Trust. Only a few yards from Hardwicke

House. Typical Norwich cartouche-style street nameplate in cast iron.

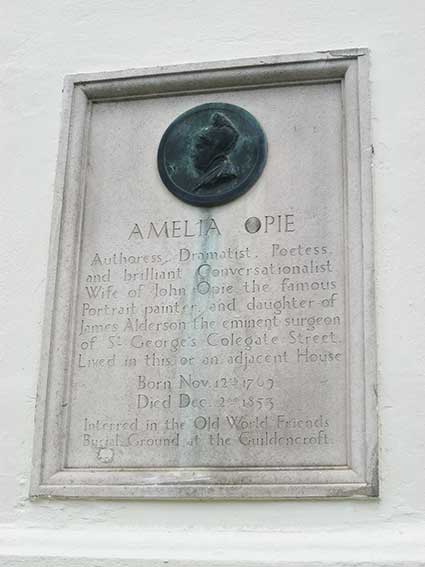

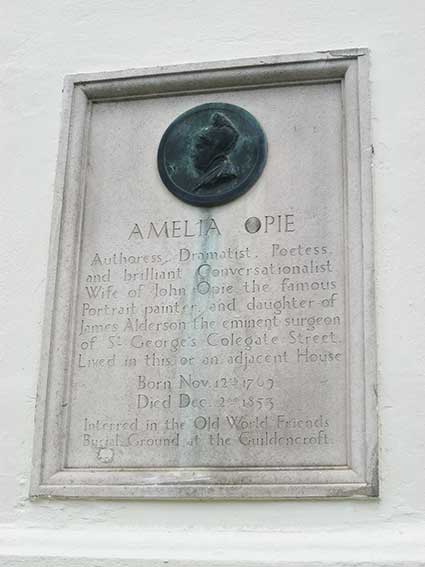

Commemorative plaque on Opie House, 26

Castle Meadow. ‘AMELIA OPIE; Authoress. Dramatist. Poetess. and

brilliant Conversationalist. Wife of John Opie the famous Portrait

painter. and daughter of James Alderson the eminent surgeon of St

George’s Colegate Street. Lived in this or an adjacent House; Born Nov.

12th 1769; Died Dec. 2nd 1853; Interred in the Old World Friends Burial

Ground at the Guildencroft.’ Copper relief porait in roundel. The

plaque and roundel are set above the ground-floor rustication to the

left of Opie House at the corner of Opie Street (building is Listed

Grade II). Amelia Opie is seen in profile wearing a peaked Quaker

bonnet, based on the 1829 bronze medallion by David d’Angers, who in

1836 carved a more idealised marble bust, versions of which are in the

Musée des Beaux Arts, Angers and the Castle Museum Norwich, acquired

2008. The date of the plaque is not known but H.A. Miller had begun

producing these plaques with that to George Borrow in 1913. Opie House

had been acquired by Mr Keefe, a solicitor, in 1932 by which date the

plaque was presumably in place. (Description from Norfolk & Suffolk

Public sculpture website (see Links).

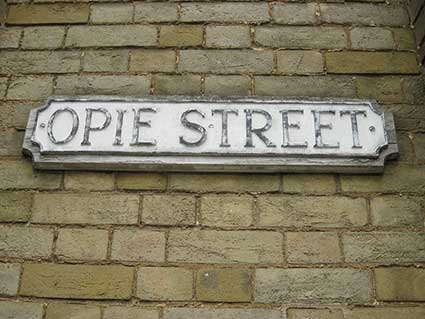

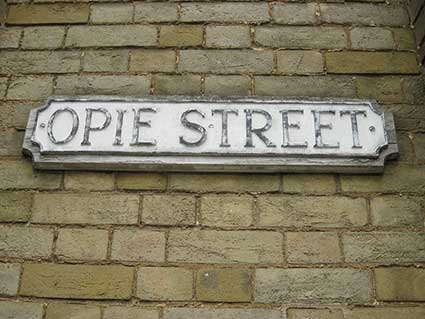

Above right: ‘OPIE STREET’ street

nameplate mounted on shaped board on the white brick of Castle

Chambers. Opie Street was originally called Devil’s

Steps but was renamed after a local girl, Amelia Opie – see above.

Castle Chambers, Opie Street.

This building is Listed Grade II and was built in 1877 for solicitor

Sydney Cozens-Hardy who had founded his practice in 1873. The building

features yellow/buff brick with terra cotta decoration. The firm of

Cozens-Hardy LLP continues to occupy the building. On

the main entrance to Castle Chambers, the pediment

bears the building name lettering in relief, picked out in colour with

numerals above : a fine date monogram of '1877'; note the

flattened top of the '8'. The ‘SCH’ monogram (for Sydney

Cozens-Hardy) is in circle centred above each window

and doorway at ground and first floor level.

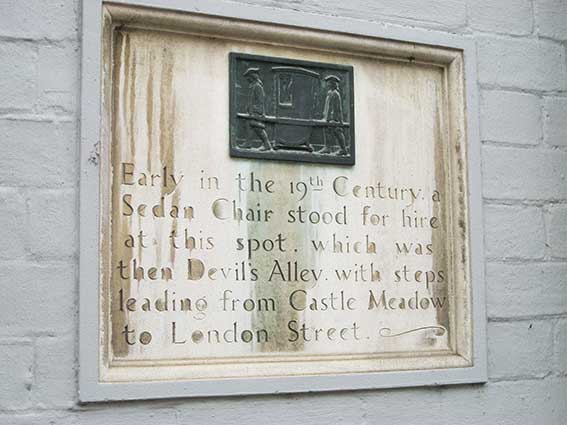

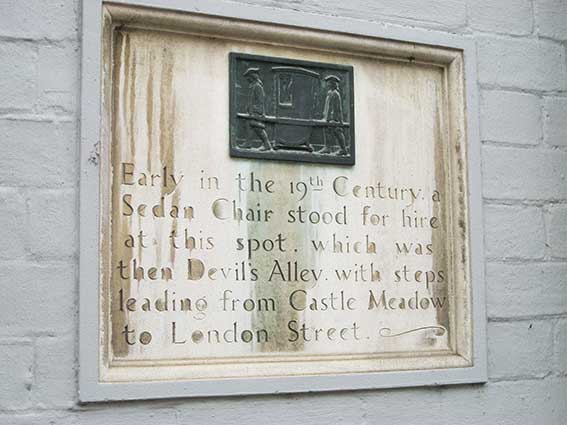

Corner of Opie Street and

London Street:

Sedan chair plaque. ‘Early in the

19th Century, a Sedan Chair stood for hire at this spot. which was then

Devil's Alley, with steps leading from Castle Meadow to London Street.’

57 London Street.

‘1844’; ‘1960’; ‘1900’. Dated plaques above the second storey windows

of this sandstone building.

53 London Street (junction with

Bedford Street): Fire Point plate, ‘No. 74; FP; 13ft,

6in’. Overpainted in the green of the window surrounds and later

restored to the original black characters and frame on a white

background.

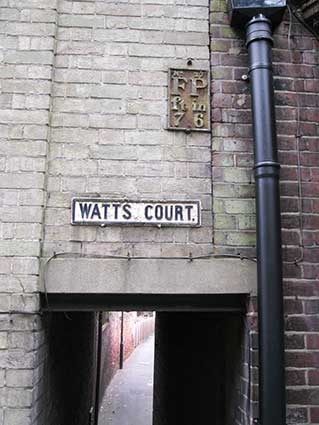

‘Hydrants

Although an Act of 1774 required each parish to maintain their own

fire-fighting appliance, to be used by the local citizens when

required, fire fighting was largely the responsibility of the insurance

companies. By the mid 19th century the police were charged with

providing a fire fighting service and wore distinctive uniforms

(usually styled on naval practice). Water supplies for fire fighting

were something of a problem but from the 1830s on most towns included

bye-laws to force the water supply company (whether private or owned by

the town) to fit hydrants to the water mains. From about the 1890s the

hydrants were usually marked by a cast metal plate mounted high up

(typically at the hight of a second floor window) on a nearby wall.

Early examples were white with black markings, usually the letters F H

(‘Fire Hydrant’) or F P (‘Fire Point’) and a number such as 7 0

indicating the distance in feet between the hydrant and the plate.

During the Second World War any suitable water supply was marked by the

letters 'E.W.S.' painted in white or yellow in letters about two feet

(60cm) high on a suitable nearby wall. This marking was still seen into

the 1960s on bridges over rivers and on walls close by ponds and the

like. After the second world war a national standard was introduced

consisting of a cast metal plate about ten inches (25cm) high by six

inches (15cm) wide. This plate is yellow with a large letter H in black

and the distance to the hydrant in smaller black numbers between the

lower legs of the H. In some cases the older F P plates have been

painted yellow with the lettering picked out in black, however as they

are often hard to reach many remain in the original black and white.

The post war hydrant plates are often seen mounted on stubby concrete

posts set into the pavement. [Notes

taken from: https://www.igg.org.uk/rail/00-app1/st-furn.htm]

Scroll down for a Fire Point plate at Watts Court. Note also the

vestigial 'E.W.S.' (Emergency Water Supply) sign in Lower Orwell Street, Ipswich. There is another 'EWS' example in Appleby-in-Westmorland.

‘Bedford Street’ and St Andrews Hill’

cartouche-style, cast iron street nameplates. With explanatory

historical panels below.

30 London Street: former London

And Provincial Bank. Built from Portland stone, and designed by

the Norwich architect George Skipper (see also the Royal Arcade, below)

in 1906/08.

Listed Grade II: ‘Portland stone. Roof not visible. 3- storeys. 4 bays.

Rusticated

ground floor with door in right-hand bay with marble Doric columns

supporting architrave and broken pediment in round- headed recess.

Ground floor windows in semi-circular hollow-chamfered arches with

Keystone. Sash windows with pedimented surround and Vitruvian scroll

stringcourse at first floor. Oval windows at 2nd floor. The first and

2nd floor windows are divided by attached Corinthian columns. 3-tier

bowed window above entry supported by putti. Extravagant use of swag

decoration at 2nd floor level. Modillion fascia cornice displaying

‘London and Provincial Bank’. Fine ground floor plaster-work ceiling to

original banking hall.’

19 Castle Street: Dipple

and Conway Ltd, opticians' premises for three

generations

bears the company name in stylish characters and an excellent hanging pince-nez sign. The plaque next to

it reads:

‘REBUILT

IN THE JUBILEE YEAR

OF THE BEST OF KINGS

MDCCCIX.' [1809 ; George III]

Royal Arcade, junction of

Castle Street, Arcade Street, Back of the Inns.

'Designed by local architect George Skipper in the Arts and Crafts

style popular at the end of the nineteenth century, the Royal Arcade

was built on the site of an old coaching inn and was unveiled on the

25th May 1899. On the next day the Eastern

Daily Press newspaper reported that ‘The general view of it is

pleasing in the extreme, and there can be no doubt it will prove a

permanent attraction to visitors, no less than to the townsfolk’.

Viewed from Gentleman's Walk the Arcade's façade is unremarkable and

offers little hint of the architectural extravaganza to be found

within. The single storey entrance opens up almost immediately into the

arcade itself, two storeys in height, 247 feet (75 metres) in length

and tiled throughout in pastel shades of greens and creams. With its

fully glazed roof supported by slim timber arches the whole interior is

light and airy.

The shop fronts are all to an almost identical design and are lightly

framed in a rich mahogany or similarly coloured wood. They project

slightly forwards into the arcade, with large bowed windows and are

quite exquisite. Above each and elsewhere in the arcade are panels of

decorative coloured tiles depicting peacocks and flowers, manufactured

by Doulton and designed by the ceramic sculptor W. J. Neatby, perhaps

best known for the tiles in Harrods food hall in London. The hanging

lanterns and flooring are new, dating from the extensive restoration of

the Arcade in the late 1980s.

At the far end of the Arcade, and over the entrance from that end, is a

large semicircular window, glazed with a mosaic in stained glass

depicting trees and birds. On leaving the Arcade here and looking back

one is confronted by a most spectacular façade, which extends to the

properties to either side, with more tiles and the aforementioned

window, all topped by an angel with wings reaching to the sky. Just

inside the arcade from the Gentleman's Walk entrance is Langley's toy

shop, which has had a presence in the arcade, though originally as

Galpins, ever since the arcade opened in 1899.

In medieval times the importance of Norwich as a provincial centre had

been assured, in large part due to the prosperity brought by the

textile trade in and around the city. The road at the lower end of the

marketplace was then known as Nether Row and was a natural location for

the fine houses and coaching inns which were built as a result of this

trade. By Georgian times the city had become a fashionable shopping

destination, and there were at least four such inns, together with

shops selling luxury goods, along this side of the market, which by now

had been renamed as Gentleman's Walk. The inns had long yards to the

rear, leading to a street aptly named as Back of the Inns, with stables

to accommodate the changes of horses for the stagecoaches. The largest

of the inns was the Angel, possibly dating back to the fifteenth

century or even earlier. The Angel was not only a coaching inn but also

served as a venue for public meetings, the local headquarters of the

Whig party, and a place of lively entertainment.

In 1840 the Angel was sold, renamed the Royal Hotel in celebration of

the marriage of Queen Victoria to Prince Albert, and refurbished ‘with

every convenience for the reception of families and commercial

gentlemen’. By this time the era of travel by stagecoach was almost at

an end. The arrival of the railways had reduced the travel time between

Norwich and London from fourteen hours to only a fraction of that and,

in early 1846, the Norfolk Chronicle

announced that ‘All the coaches between Norwich and London have ceased

to run’. In that same year a new frontage was built to the Royal, and

the hotel remained in business there until 1897, when it moved to newly

built premises at Bank Plain, closer to the main railway station. It

was on the site of the old hotel and its yard that the Royal Arcade was

opened just two years later. The hotel's frontage was retained and

still serves as the entrance to the arcade from Gentleman's Walk.'

[Notes from https://www.norwich360.com/royalarcade.html]

Royal Arcade,

Conservative Club entrance (Gentleman's Walk end).

13 Chapel Field North: St

Mary’s Croft, overlooking Chapefield Gardens. This

house is Listed Grade II: ‘Late 19th century red brick

and pantile, two storeys and

attic. Three bays with smaller recessed central bay. Important example

of Tudor Revival. Moulded assymetrical porch with curvilinear gable and

finials. Mullion and transom windows with hoodmoulds. String courses

made of moulded brick panels. Decorative saw tooth cornice. Second

floor attic verandahs in outer bays with primitive carved posts.

Central dormer with curvilinear gable; these gables also at ends of

house with stacks. Verandahs have hipped tile hung roofs with

pinnacles.’

St Mary's Croft was

built by Captain Crowe in 1881, incorporating the walls of an earlier

building. It stands out because of the two 2nd floor verandahs with

carved cornerposts, low balustrading and hipped tile-hung roofs with

pinnacles. The boundary walls and railings of this property are also

Listed. The deep carving of the relief capitals on the name plaque has

resulted in the downstroke of the 'N' to become detached; it is still a

fine decorative piece of lettering.

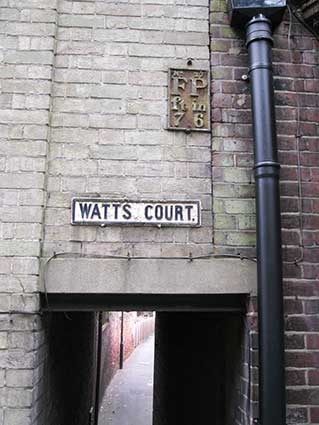

Watts Court. Fire Point

plate, ‘No. 27; FP; 7ft 6in’. Entrance to ‘WATTS COURT.’ by 11 Chapel

Field. Above right: Watts Court, the passage.

66 Bethel Street: ‘TURRET

COTTAGE’. Listed Grade II: 'Former house now office. Early C19. Red

brick painted on west facade. Pantile roof. Corner site. 3 storeys plus

semi-basement. Single bay. Door in west elevation with semi-circular

fanlight and wrought-iron trellis-work porch. Sash windows with glazing

bars and rubbed brick flat arches in Bethel Street elevation. Fascia

cornice.'

The degraded capital letters are painted on a white background

following the course of the brickwork. The state of the

side wall suggests that another property occupied the space to the left.

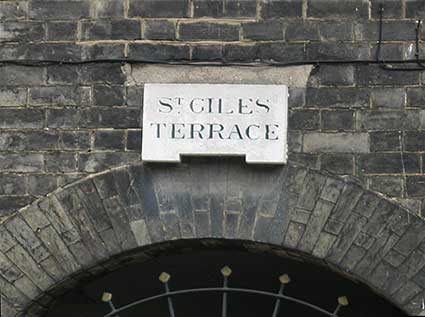

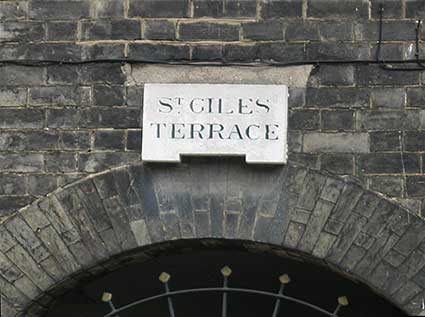

'St Giles Terrace', Bethel

Street: arched entry with name tablet above. Tucked away behind

the

buildings on its north side of Bethel Street is a row of town houses

known

as St Giles Terrace, built during the early part of the 19th century.

Facing west, its grey brick facade was designed with a series of five

brick pilasters supporting a shallow stone pediment above a plain

architrave.

30 Bethel Street: The

Old Fire Station. Now Sir Isaac Newton Sixth Form

College. At a

higher level is an Art Deco stone feature with the Norwich City coat of

arms (castle with rampant lion below on a shield) and the date ‘AD

[below the shield] 1934’.

Gaol Hill: Drinking

fountain, east end of Guildhall. ‘1859; presented by Charles P. Melly;

Above: ‘C.M.’ [Charles Melly]; ’S.R.’ [Salve Regina: 'God save the

Queen'].

The panels with shields are worn but the coats of arms on the right can

be made out as those of the City. The drinking fountain is also badly

worn. The decorative fountain has a mock-Gothic architectural frame and

the red granite drinking trough is supported on a twisted all'antica or

early Christian column. This is very much more elaborate than the

simple granite fountains which Melly had provided for Liverpool,

discussed below. It may have been designed by Robert Kerr, the

architect responsible for the clock tower of 1850.

The provision of a drinking fountain fits with the Victorian response

to the discovery in 1854 by John Snow (1813-1858) that cholera was

spread by contaminated drinking water, and with a philanthropical

movement initiated by Charles Pierre Melly (1829-1888). Melly was born

in in Tuebrook (a suburb of Liverpool), to a Swiss father from Geneva,

who had gained English citizenship. Charles Melly became a cotton

merchant in Liverpool & Manchester, an officer in the Childwall

Rifles and a philanthropist. He was involved in planning Sefton Park,

Liverpool, having persuaded Lord Derby to donate land. He founded the

North East Mission; the first night school, in Beaufort Street; and the

Liverpool Gymnasium, in Myrtle Street. Concerned for Liverpool’s poor,

he provided free playgrounds for children and benches for the elderly,

and, having seen the difficulties of the lamplighters, he introduced a

system he had seen in Geneva, replacing ladders with long poles. In

1852, having been told of the dock workers’ and immigrants’ need for

fresh drinking water - their only alternative being the public house -

he proposed the provision of free drinking fountains, based on those in

Geneva. Initially, he set up a number of taps near the docks, providing

fresh water, but these proved so popular (on one occasion, in a 12 hour

period, they were used by not less than 2336 people!) that they wore

out in two years. In 1854, at the south end of Princes Dock, Melly set

up the first red granite fountain, and by 1858 he had supplied

Liverpool with 43 fountains, with water spouts including lions’,

tigers’ and satyrs’ heads, and all at a cost of £10 each. Attached to

dock walls, church walls, railway station buildings and bridges, and

other places where they would be most useful for the poor. Melly’s fame

spread, and a paper which he presented to the Liverpool meeting of the

national Association for the Promotion of Social Science in 1858,

outlining his work in the city, was taken up by Samuel Gurney MP

(1813-1882) a nephew of the Quaker prison reformer Elizabeth Fry, MP

for Penryn, 1857-65, and a founder of the Metropolitan Drinking

Fountain & Cattle Trough Association. Although Gurney lived in

Surrey and at Regent's Park he was one of the members of the Norwich

based Overend and Gurney Bank not to have been damaged by their crash

in 1866, a connection which may have prompted Melly to have presented

one of his drinking fountains to Norwich and may explain its prominent

position at the east end of the Guildhall, still the City's town hall.

The need for the fountain is a further indication of the decline of the

city's once great textile business, which by the 1850s had failed to

keep up with Manchester in the use of the power looms. This resulted in

large-scale unemployment and unrest among the city’s weavers,

compounded by the appalling quality of the water, noted in a report for

the General Board of Health in 1851. The Wensum was 'thoroughly and

irremediably' polluted with domestic and industrial waste, although

piped water had become available following the establishment of a new

water company in 1850. Following Melly's example Samuel Gurney set up

London’s first fountain on the wall of St Sepulchre, Holburn in 1859.

Melly's example and Snow's discovery of the link between contaminated

water and cholera was to result in widespread commissions for fountains

and water pumps, including in Norwich the Gurney obelisk of 1860 on

Tombland (designed by John Bell) and that endowed by Sir John Boileau

in 1869 for the Newmarket and Ipswich roads. [Information from the Norfolk

& Suffolk Public Sculpture database (see Links)]

Above left: Gaol Hill,

Guildhall. Plaque at the upper right of the

Melly drinking fountain, east end. ‘Thomas Bilney, 1495-1531, First

Protestant Martyr Imprisoned in the vault below prior to execution by

burning at Lollards Pit on, 19 August 1531’. Lollards Pit was on

Riverside Road, occupied today by the Bridge House public house. Bilney

was a well-known preacher against idolatry; at Ipswich, he denounced

pilgrimages to popular shrines like Our Lady of Walsingham and warned

of the worthlessness of prayers to the saints – he was pulled from the

pulpit of St George’s Chapel by some members of the congregation.

Thomas Bilney, a Norfolk man born near Dereham, was a Cambridge

academic. Like the Lollard priest William White before him, he was

convinced that the Church had to be reformed. Arrested, and taken

before Cardinal Wolsey, he recanted denied his beliefs. But,

characteristic of many who recanted when initially faced with

execution, he began preaching heresy in the streets and fields. Bishop

Nix of Norwich had him arrested, and this time there was no mercy. Like

other heretics Bilney was tried by the Church, but given to the agents

of the State for execution. ‘Good people, I am come here to die’,

declared Bilney as he stood at the stake.

[https://www.edp24.co.uk/norfolk-life-2-1786/norfolk-history/62-lollards-pit-norwich-1-214172]

Bilney appears again in our Ipswich pages about the Chapel of St George

in St Georges Street.

Above right: Gaol Hill, Guildhall. ‘NORWICH CHIEF

CONSTABLE’. Over a window to the left of the Melly drinking fountain.

The Guildhall is not just one of the finest buildings in the city, it

is one of the best of its kind in the land, but one which has been

neglected over the centuries. It is the largest and most elaborate

medieval city hall outside London, reflecting Norwich’s status as one

of England’s wealthiest and most powerful cities. For hundreds of years

this was where the people who controlled the city met in their grand

council chamber, where those in trouble stood in the dock, and where

prisoners were held in both an open jail and dungeons before being put

to death, tortured or sent to the other side of the world. It was

constructed between 1407 and 1413 and served as the seat of city

government (also court and gaol) from the early 15th century until

1938, when it was replaced by the newly built City Hall. At the time of

the building's construction and for much of its history Norwich was one

of the largest and wealthiest cities in England, and today the

Guildhall is the largest surviving medieval civic building in the

country outside London. Magistrates' Courts continued to be held in the

old Common Council Chamber until 1977 and prisoners were held in the

building until 1980. Clearly the Chief Constable had his offices at the

Guildhall, too.

Gaol Hill, Guildhall Clock tower.

This grand stonework bears two angels holding the City coat of arms

with, on a scroll at the top, the date ‘1850’. The fine gold on

grey-blue clock face has lettering below it: SOLA VIRTUS … INVICTA’

[Virtue alone cannot be conquered]; ‘HENRY WOODCOCK MAYOR’ in Gothic

script.

New council chamber, 1536, clock tower 1850. Norwich had been

granted its first Charter of Incorporation in 1404, giving it the

status of a city and the right to elect its own mayor, collect its own

taxes and hold its own Courts of Law. The Guildhall was built from

1407-53 to house the courts together with the prisoners, as well as

offices for raising taxes, the civic regalia and the civic officials.

With three major chambers it was larger than any comparable

contemporary civic building. When the roof of the mayoral council

chamber collapsed in 1511 repair and rebuilding could be put off until

1535-1537. The new chamber’s eastern façade provided the building’s

major view, now partially blocked behind a taxi rank. It was decorated

with chequerboard flushwork and a large window, which was set over

decorative panels displaying coats of arms. As with other contemporary

schemes, the entrance to Cardinal Wolsey’ College in Ipswich and

Hengrave Hall, the place of honour in the centre was reserved for those

of Henry VIII. They were flanked to the right by those of the city,

still just visible - a castle over a lion supported by armed angels –

and on the left the Guild of St. George, under a helmet. The heraldry

was reflected in the four lights of the east window and served to

underline the importance of the Norwich guild of St. George. Granted a

royal charter in 1417 from 1452 the guild had been closely linked with

the government of the city, with each retiring mayor as the alderman

(head) of the guild. The base of the clock turret is dated 1850 and

supported by angels holding the city’s coat of arms. The gilded

inscription at its base reads HENRY WOODCOCK, MAYOR and on the base of

the clock SOLA VIRTUS INVICTA (Virtue alone cannot be conquered), the

motto of the Dukes of Norfolk, the premier dukes who, in spite of their

title, had no connection with Norfolk.

The elegant arched spire, apparently rebuilt before 1935, marked out

the east end of the Guildhall from the surrounding late Victorian

buildings and the market, before construction of the present City Hall.

Henry Woodcock (1789-1879) was mayor for 1849-1851. On the 17th April

1850 he offered to provide an illuminated clock ant turret, on

condition that the Corporation removed the false ceiling in the Council

Chamber in the Guildhall and laid open the new roof. By 2008 both the

iron support for the clock and its stone housing needed repair,

undertaken from July 2010 by Universal Stone and completed in December

2011. The deterioration of the stone was worse than had been expected

so that the stone casing had to be removed completely before

restoration could begin in summer 2011. [Information

from the Norfolk

& Suffolk Public Sculpture database (see Links)]

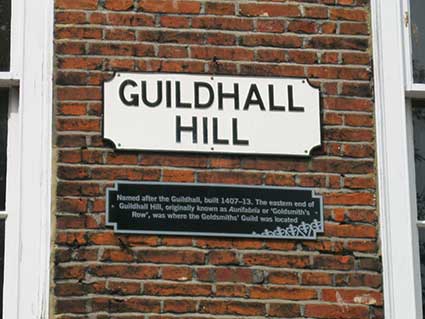

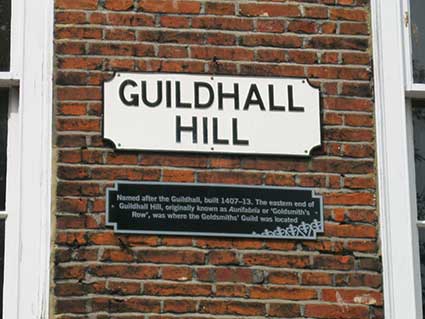

9 Guildhall Hill: street

nameplate above shopfront. A variant to the other

rectilinear cartouche-style, cast

iron nameplates in Norwich with more conventional curved quadrants

taken out of each corner. A heritage information plaque

has been mounted beneath it.

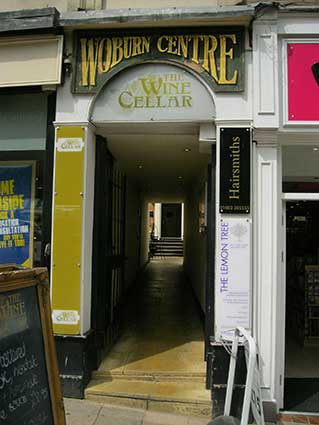

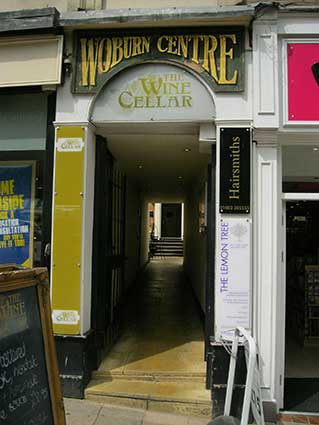

Between 7 and 8 Guildhall Hill:

‘Woburn Centre’ entrance. One of the courts and yards of old Norwich,

often associated with inns. Woburn Court is now occupied by eating and

drinking establishments. See also the 'Library' lettering at 4a

Guildhall Hill (below).

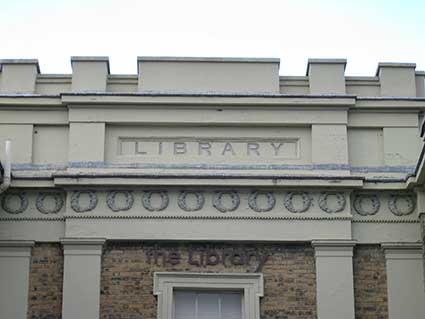

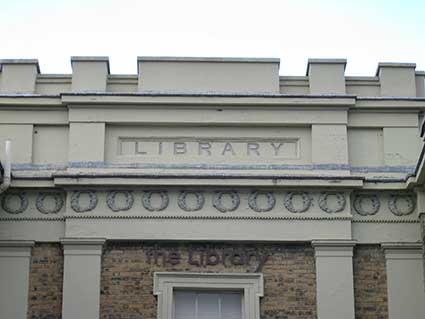

4A Guildhall Hill: ‘LIBRARY’

carved into stone cornice. The Norfolk and Norwich Subscription

Library was formed in 1886. The original subscription rate was £1 for

ladies over 18 and £2 for men. Fueled by voluntary subscriptions, the

building possessed many volumes of great value. In 1898, during the

August Bank Holiday weekend, a fire broke out in nearby Dove Street.

The fire quickly spread to the Library and within an hour the entire

building was gutted and most of its contents were destroyed. The

building was later restored at the cost of £1,719 and re-opened in

1914. The Library was indeed, the first public subscription library in

the UK and is a Listed building which has been brought to life,

sympathetically converted into a modern contemporary restaurant that

incorporates the historical features seamlessly.

Listed Grade II: 'Former library, now Court Office and Shops. 1837 by

J.T. Patience. Yellow brick with masonry dressings, Slate roofs,

Recessed block with long wings returning to the street-line having 4-

and 2-bay fronts. 2 storeys. Single wide bay. Central double-door with

tetrastyle Greek Doric portico with pediment. 3 steps up. The portico

frieze returns to become stringcourse on the facade supported by

pilasters. The centre of the facade projects with one sash window with

glazing bars and eared surround. 4 first-floor pilasters. Triple

frieze-cornice, the centre one displaying 'Library'. Pediment. Wings:-

3 storeys plus semi-basement, 11 bays, the centre 4 recessed. Sash

windows throughout with glazing bars and rubbed brick flat arches.

Masonry bands at ground and first floor. Parapet. C19 and C20 altered

shopfronts returning 3 bays along the wings. Carriage entry at extreme

left-hand side of street facades, C19 fascia between consoles above

left-hand shopfront. Corner and central pilasters. The shopfront to the

right of the carriage entry has a triglyph frieze extending across from

No. 1 Guildhall Hill. Decorative ironwork balustrading above frieze.

Sash windows throughout with glazing bars and rubbed brick flat arches

at first floor. Second floor windows beneath cornice.'

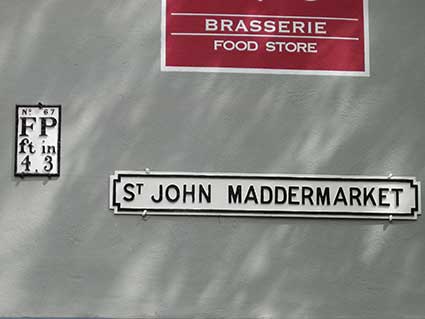

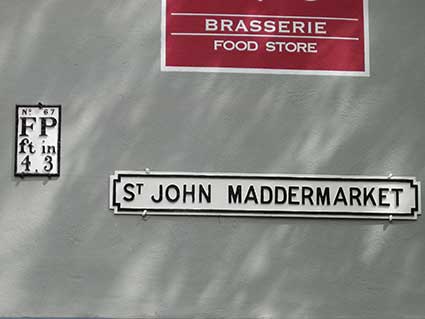

'St John Maddermarket'

street nameplate – near the crossroads with Pottergate,

Dove Street and Lobster Lane. Also Fire Point (water

hydrant) plate: ‘No. 67; FP; 4ft 3in’. The street name dates to the

early 15th century when the Guildhall was built and Maddermarket was

the

centre of the dyeing trade, madder being a red pigment obtained from

the

root of the Eurasian madder plant.

‘School Lane.’ street

nameplate and boundary marker plaque. This passageway runs between

Bedford Street (at the rear of Jarrolds store) and Exchange Street

(between Exchange Street Buildings – included below – and no. 33) and

is clearly signed at

each end, yet it doesn’t appear on modern maps. Note the unnecessary

full stop. The nearby plaque

reads: ‘X; S.A; 1832’ and is a parish boundary marker for the Church of

St Andrew which is situated nearby on the junction of St Andrews Street

and St Andrews Hill. To avoid risking damage to the nameplate and sign

during removal and reattachment, a modern cement render has been built

up around the signs.

Corner of Bedford Street and Swan Lane:

Architectural photograph. Fabric Warehouse (now Turtle Bay). Note: Fire

Point plate just visible next to first floor window on Bedford Street

elevation.

Bridewell Museum, Bridewell

Alley: William Appleyard memorial tablet.

William Appleyard was three times Sheriff and five times

City Mayor. William was the first Mayor of the City after it became a

shire incorporate in 1404. He owned lots of property in the city and

inherited from his father the house that now incorporates the Bridewell

Museum, famed for it’s finely-cut black flint bricks. William presented

the city with a great tree to aid with building the new Guildhall. He

also owned a lot of land to the south of the city, including Intwood,

Bracon Ash and Hethel. His father was given the rather odd

responsibility of providing the King with 224 herring pasties whenever

he visited the region.

Around 1325 a wealthy merchant named Geoffrey de Salle built a house

here, near the Church of St Andrew. In 1386 the house was enlarged by

William Appleyard, who went on to become the first mayor of Norwich

(1403-1435). Very little of the original 14th century building

survives, save the flintwork facade facing the narrow lane linking

Bridewell Alley and St Andrews Hill (both still paved with setts). This

is one of the earliest and finest examples of secular East Anglian

flintwork in England. Under the building is another 14th century

survival: the vaulted undercroft, used for storage and to hold inmates

when the house became a prison. Bridewell Prison was established here

in 1585 and was named after the London prison of the same name which

was built near St Bride’s Well. The Bridewell must have been a very

desirable property, as by the 16th

century it was owned by another Mayor of Norwich, Robert Gardener. Then

in 1580 it was sold to the Corporation of Norwich by John Sotherton.

The Corporation had a problem: the city was bursting with

transient beggars and poor residents, drawn by Norwich's reputation as

a bustling centre of commerce. But these beggars and poor people relied

on the city for charity.

Corner of Princes Street and

Elm Hill: Building decorated with boundary

marker-plates. The plates are fixed to brickwork at first floor

level; note the crow-steps on the gable above.

The plates read:

‘X; S A; 1813’ [parish of St Andrew]

‘X; S A; 1832’ [parish of St Andrew]

‘H; S P; 1814’ [parish of St Peter Hungate]

‘H; S P; 1834’ [parish of St Peter Hungate].

N.B.: other small collections of boundary marker-plates can be seen on

buildings further down Elm Hill, presumably collected by the residents

during changes to or demolition of the original bearers of the markers.

Above left: Princes Street

(opposite 56-57 building). Wall-mounted gas lamp

(now converted to electricity) with number ‘2073’ stencilled on

white-painted brick below.

Above right: Elm Hill.

Wall-mounted gas lamp on corner house at the top of Elm Hill (now a

café). The number ‘2049’ is stencilled on the lower body of the lamp;

situated next to the ‘ELM HILL’ street nameplate. Both examples appear

to have been replaced since the photographs were taken in 2013 by

larger lamps with amber-coloured opaque glass. Numbers are ‘2’ and ‘1’

respectively with new numbers stuck on the bottom of the front glass

panel. Do they look as good/authentic?

Princes

Street United

Reform Church. The extravagantly decorated arched entrance at

the

centre of the palladian facade features subtly-serif’d capital letters

floating over the carved floral features: ‘ENTER INTO HIS COURT WITH

PRAISE’ (a version of Psalm 100:4 KJV: ‘Enter into his gates with

thanksgiving’). The white brick frontage features pilasters with

equally extravagant Corinthian capitals below the cornice. Two more of

the street lanterns project from the side pilasters.

Plumbers Arms Alley, 20 Princes

Street. Runs into Waggon & Horses Lane (named after the

former inn of the same name). The alley is named after the Plumbers

Arms public house which used to be located here, with the first

recorded licensee having been Margaret Dawson in 1822. Two more

examples of numbered, wall-mounted gas lamps are visible.

7 Tombland: the

Edith Cavell public house. Frosted door decoration (probably modern

adhesive vinyl?): ‘BOTTLE AND JUG ENTRANCE; THE EDITH CAVELL’. The

colour scheme has since changed.

Beside the Erpingham Gate in Tombland is a monument to Edith

Cavell, who was born just outside the city of Norwich. Cavell is famous

for her role in helping allied servicemen to escape from occupied

Belgium during World War I. She was eventually discovered and shot, but

later brought to Norwich Cathedral for burial.

Scroll down for other examples in Tombland (The Augustine

Steward

House, The Maids Head Hotel).

24 Tombland: 'ST

ETHELBERTS' lettered below the second storey window of the central

gable. Named after the St Ethelbert’s Gate in nearby Queen Street. This

gate to the Cathedral Close dates from c.1316. St Ethelberts House,

Tombland: This is a swagger Arts-and-Crafts style house of 1888, with a

welter of mullions and transoms, coving and gables.

Listed Grade II: 'Former use unknown, now restaurant and club. 1888 on

plaque by E.P. Wilkins [to the right]. Red brick and rendered. Hung and

plain-tiles. 2 storeys plus attic.

Symmetrical bays plus one bay. Central door with hood on consoles and

large shell moulding. Yard entry at extreme left with open pediment.

Circular windows with scrolled and pedimented surrounds and 6-light

mullion and transome windows at ground floor. First floor dentil

stringcourse across 4 bays. Oriel windows at first floor with swags

between. Coved cornice and decorated parapet. 3 large dormer gables

with casement windows: bargeboards with finial in outer bays and

central dormer with pediment. Mansard roof with decorated tiles. Single

right-hand bay:- door at extreme right with moulded stone surround and

broken pediment. 2 mullion and transome windows at ground floor. Canted

first floor window with brick pediment and apron . Dutch gable. 5 lamp

posts in front of facade.'

Redwell Street: ‘Forget

Me Not, 1827’ clockface, St Michael-At-Plea Church. 14th century church

with a rather distressed clockface; it looks as if the four studs are

made of iron and rust stains are evident. The red background was

probably a richer. deeper red, similar to that used on the information

board below it. The sign over the entrance door reads 'SHOP & CAFE'.

3-7 Redwell Street: Clement

Court.

Plaque on modern clock: ‘Near this spot on 6th September

1701 Frances Burges published the first number of The Norwich Post, the

first English newspaper’. City arms at the top; horn-blowing rider on

horseback at the bottom of the plaque. The building is now Francis

House,

part of Norwich University of the Arts.

5 Orford Hill/Red Lion Street, Bell

Hotel. Large capitals in relief at the top of the

building ‘BELL HOTEL’ with projecting half-bell (Orford Hill: Santander

branch).

Large capitals in relief at the top of the building ‘BELL HOTEL’ with

half-bell and clock above on angled wall (Red Lion Street:

Wetherspoon’s pub).

Junction of Red Lion Street

with Farmers Avenue and Castle Meadow (opposite the Bell Hotel).

‘YORK HOUSE.’ in capitals with a superfluous full stop

in panel in

gable. York House once used to be a pub known as the 'York Tavern' in

1884. From 1760 until 1807 it had been called the 'City of York' or

'York City'. By 1840 it was a shop but apparently became a pub once

again which was finally closed in April 1964.

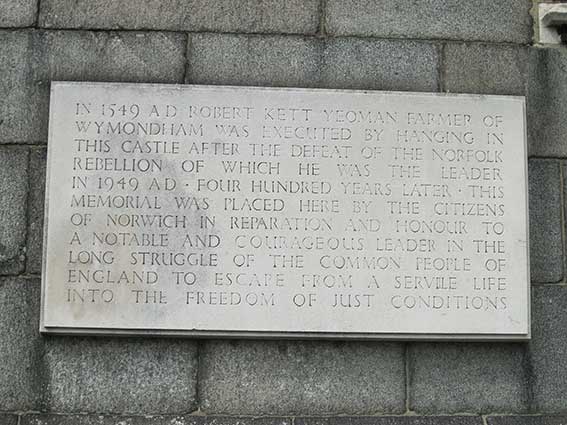

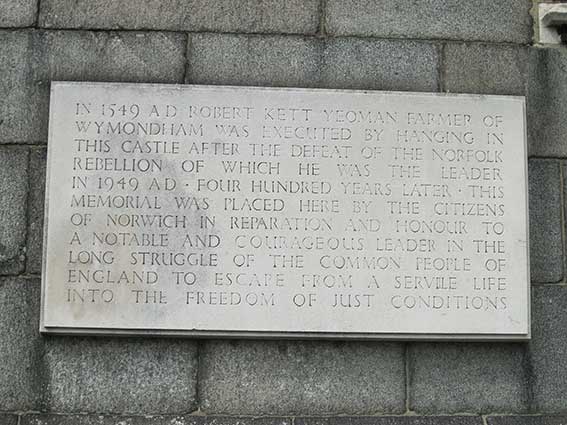

Norwich Castle plaque: ‘In 1549

AD Robert Kett yeoman farmer of Wymondham was executed by hanging in

this castle after the defeat of the Norfolk Rebellion of which he was

the leader In 1949 AD - four hundred years later - this memorial was

placed here by the citizens of Norwich in reparation and honour to a

notable and courageous leader in the long struggle of the common people

of England to escape from a servile life into the freedom of just

conditions’. Sited beside the main visitor entrance.

5 Orford Street: ‘ORFORD

Place, 1809’ plaque. The date numerals are placed in

each

corner; it looks as if the plaque was white and has been painted in a

slapdash manner with a terra cotta colour.

8 Orford Hill.

Architectural photograph: sculpture of a large stag at roof level (a

former inn?).

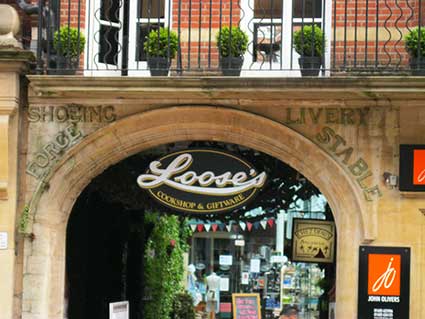

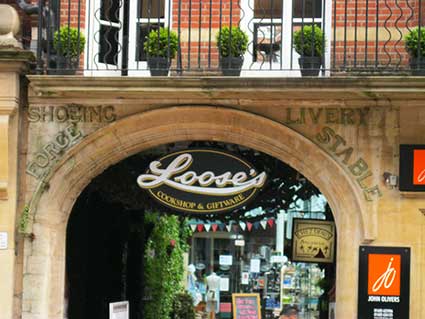

5 Red Lion Street

(formerly Loose’s cook shop). Above the arched carriage entrance:

‘SHOEING; FORGE; LIVERY; STABLE’ in metal characters attached to the

stone. On the decorative gable (5th storey) brickwork: ‘1902’ in large,

separated metal characters. Presumably an old coaching inn?

23-25 Red Lion Street: 'ANCHOR

BUILDINGS'. Roundels in pediments to side inscribed with intertwined

‘BS’ monogram (for Bullard and Sons, brewers). In cartouche set in

central pediment an anchor and chain with rocks a version of the

brewery emblem from 1868 on display at Bullard’s Anchor Brewery on

Anchor Quay. The street was widened and rebuilt from 1900 onwards. The

Anchor buildings were built by Bullards with the Orford Arms in the

left hand building. The Orford Arms (a Bullards pub) had been on the

site since at least 1865. William Grix was the licensee from 1900-1905.

The last licensee was recorded in 1937.

The monogram bears a striking resemblance to the design of that used by

Norwich brewer Steward & Patteson Ltd (as seen on Uncle Tom’s Cabin in Ipswich).

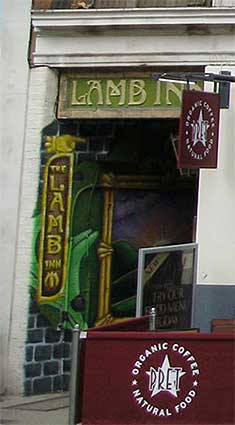

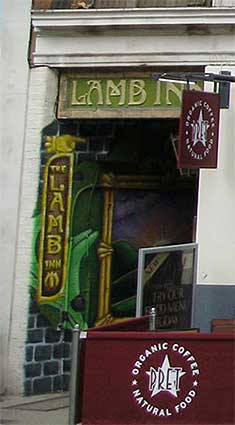

11 Haymarket: ‘LAMB

INN’ in ceramic tiling. Dated 1902 and apparently designed by George

Skipper, architect of the Royal Arcade and the London

And Provincial Bank, in London Street (see both,

above). The Baroque

flourishes make that seem entirely plausible. Clad in an eclectic mix

of coloured faience and stone. Reputed to be the best building in

Norwich not to be Listed (it is on the city council's Local

list). The Art Nouveau lettering fits the date of the building.

The name The Lamb takes the pub back to its 13th century origins when

it was known as the Holy Lamb. The pub building in Lamb Yard is dated

late 18th century.

16 Gentlemans Walk, Lloyds

Bank building. Listed Grade II: ’1924 by H. Munro Cautley and extended

into Davey Place

in 1925. Stone. Slate and flat roofs. Corner site. 6 major bays, one

minor bay to left and corner bay to right. Corner and end entrances

with bolection bead and rod surround and lintol with figure-head

keystone supported on scrolls. Above the lintel is a cartouche

supported by putti. The ground floor has metal casement windows with

margin lights and flat arches having bead and rod decoration. Recessed

panels beneath the semi-circular arched first floor windows: scrolled

keystones and festoons in the spandrels. Square casement windows at top

floor. Glazing bars throughout. Heavy panelled pilasters dividing the

bays with simple frieze between first and second floors. Ziggurat

cornice with lion masks and fascia motif. Rusticated hollow chamfer

surrounds to windows above passage.’

The attached metal characters above second storey level read ‘LLOYDS

BANK LIMITED’ (shortened to ‘LLOYDS BANK’ on the 45 degree-angle

entance). Stone lettering is cut in relief: ’LLOYDS BANK’ appears twice

on

the Gentlemans Walk elevation below the ground floor windows and once

on the entrance below the cartouche. ‘LLOYDS BANK LIMITED’ runs down

the Davey Place elevation. The monogram ‘LB’ is in a circle on the

upper pediment of the entrance, with ‘LLOYDS CHAMBERS’ in metal

characters above the side entrance.

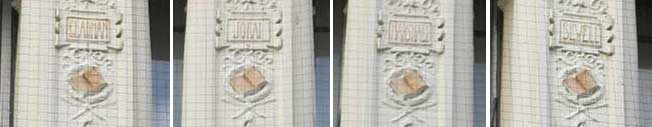

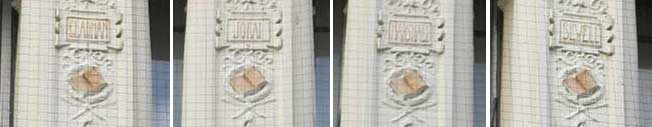

Corner of Exchange Street and

London Street: Jarrolds store. ‘JARROLDS’

moulded into the curved frontage at first floor level. Along Exchange

Street above the ground floor windows: ‘JARROLDS; BOOKSELLERS;

BOOKSELLERS; STATIONERS; JARROLDS (repeated). Pillasters at second

floor level bear decorative open book motifs with cartouches bearing

the names: ‘GLADMAN’, ‘BREWER’, ‘JOKAI’, ‘MARSHALL’, ‘SEWELL’,

‘FARNELL’, ‘SPILLING’. The spandrells around the semicircular windows

at first floor level bear ‘J’ and ‘L’ (for Jarrolds Ltd) intertwined

with olives, leaves and scrollwork then oak leaves, acorns and

scrollwork, respectively. Once again, this is the work of architect

George Skipper, creator of the Royal Arcade. The shop has been well

described by Stefan Muthesius: 'Skipper provides a most sophisticated

reflection on a problem which had bothered designers for many decades.

Ever since progress made possible large sheets of glass, store windows

were made as large as possible to display the goods inside and to let

the light in. But such a shop front might look flimsy. By way of a

complex series of supports, Skipper gives the impression of reasonably

eighty construction, while still getting across that we are looking and

into a department store. Lastly, its delicacy and relatively modest

overall size were meant to distinguish form the largish and squarish

factory piles.’ Skipper adapted the classical orders setting Ionic

above the more manly Doric. Ionic was appropriate for the upper part,

since it was traditionally linked with wisdom and so celebrated the

firm's connection with books since the names inscribed in the

cartouches (as noted by Jolley) are of authors published by Jarrolds.

The following illustrative list (all published by Jarrolds of London)

was compiled from the Abebooks website: Dr C. Brewer: History of France: political, social and

literary history to 1874, (n.d); F.J. Gladman: School work; I. Control and teaching; II.

Organization & principles of education, 1886; Maurus

Jokai: Green Book or Freedom under

the Snow, 1897; Saunders Marshall: Beautiful Joe, 1907; Mary Sewell

(mother of Anna): a number of books including Mother's Last Words; James

Spilling: Giles’ trip to London,

1872; Wm Keeling Farnell: School

steps and self instructor’s ladder to arithmetic, grammar and geography,

1857 [Notes from the Norfolk & Suffolk Public Sculpture website,

see Links.]

35-37 Exchange Street:

‘EXCHANGE ST BUILDINGS, 1906’ (beside entrance to School

Lane, see 50-52). Listed Grade II: ‘Early C19 with 1906 doorcase. Red

brick with rendered detail. Roof not visible. 3 storeys. 4 bays.

Right-hand off-centre recessed door with attached Corinthian [sic: surely they're Ionic

capitals?] columns

supporting open segmental pediment. Scrolled and eared window surround

above door. Sash windows throughout with glazing bars except in ground

floor bottom sashes. Egg and dart stringcourse between first and second

floors. Box cornice.’

30 St Benedicts Street:

'WALKERS STORES'. The name in white characters on bottle green

background is shown vertically in ceramic tiling shop surround to the

left and the right. What did Walkers Stores originally

sell? It has the look of a grocery shop.

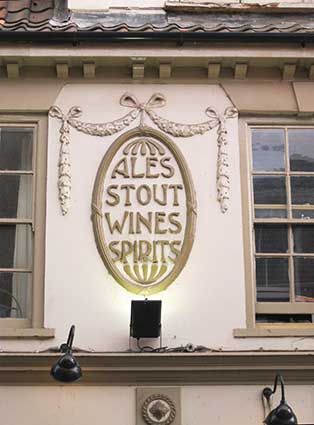

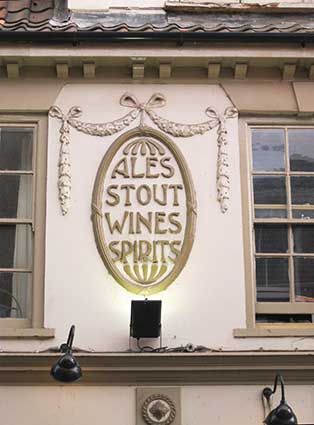

58 St Benedicts Street: The

Plough and Little Plough Yard. Two decorative ovals in the stucco at

first floor level carry a depiction of a hand-plough and ‘ALES STOUT

WINE SPIRITS’. ‘LITTLE PLOUGH YARD’ is signed above a passage entrance

to the left.

14 Tombland: the plaque

reads ‘THIS HOUSE purchased and preserved in 1924 by the Norfolk

Archaeological Trust was built AUGUSTINE STEWARD, Mercer, Sheriff 1526,

Mayor 1534,1546 and 1556, Burgess in Parliament 1547.’ On an excellent

example of a Tudor merchant’s house, the rear accessed via ‘TOMBLAND

ALLEY’ (signed above the entrance). On a corner stone above this entry

is the date ‘1549’ and Steward's merchant's mark, along with the

mercer's gild insignia. The movements in the timber-framed building

over time have resulted in some squeezed and skewed windows at second

storey level – it must be difficult to fit repalcement glass panes.

The name 'Tombland' sounds as

if it is derived from some long-lost

burial ground, situated as it is near the gates to the Norman

Cathedral, with the medieval Church of St Michael – the largest in

Norwich. However, the name comes from two Old English words meaning

'open ground', or an empty space. This open ground was used as the main

market place for Norwich; the hub of commercial activity and town life;

also for fairs. The rhythms of markets and fairs in the calendar were

of economic, social – and sometimes political – importance to

inhabitants and visitors alike.

20 Tombland: The Maids

Head Hotel. The hotel dates from the 13th century and is

amalgamation of at least six buildings. The main façade faces on to the

intersection of three streets, Tombland (see the derivation above),

Wensum Street (named after the local river) and Palace Street

(presumably because in this area was the palace of the Earl of East

Anglia). The Maids Head Bar features Jacobean Oak panelling and has

been reputedly, frequented by guests such as Horatio Nelson and Edith

Cavell. Queen Elizabeth I was said to have slept at the hotel in 1587.

The large terra cotta panel features three gothic arches with Tudor

roses and the somewhat eccentric lettering: 'ye Maid's Head Hotel.' in

a version of medieval script; the damage to the "d's" bears comparison

with the name plaque of 'St Mary’s Croft', 13 Chapel

Field North (shown above).

Listed Grade II: ‘Former uses unknown, now hotel. C15 cellars.

C16 onwards with major facade alteration in the early C20. Red brick.

Rendered. Timber-frame. Pantiles and plain tiles. The complex is an

amalgamation of at least 6 buildings, Tombland facade:- 2 storeys, 3

storeys to the left, 4 bays extended to the left by 2 bays plus comer

bays. Central C20 4-door hotel entrance with flat hood. Door at extreme

right with round arch and attached columns supporting an open pediment.

4 steps up. Sash windows in right-hand 4 bays with glazing bars and

rubbed brick flat arches. C20 casement windows above central entry.

Paired bracket cornice below parapet. 4 flat-roof dormers. 3-storied

early C20 bay and corner bay extending into Wensum Street:- Door with

moulded timber surround. Casement windows throughout, corner and right-

side oriels with gables above. The top floor has pseudo-timber framing.

3 builds in Wensum Street:- 2 and 3-storeys, jetties and carriage entry

to the north of the middle range.’

8 Surrey Street: ‘NORWICH

UNION LIFE INSURANCE SOCIETY’ sits in relief on the cornice of the

Palladian facade of a grand

stone palace of insurance, now called Aviva (the rename Norwich Union).

The company's offices in Surrey Street, known as ‘Bignold House’ (named

after Thomas Bignold, founder of the company), were built as a private

house for the Patteson family. Rooms in the house were heated by

fireplaces, some of which were designed by Sir John Soane, and clerks

were expected to bring in a pound of coal for each day

they worked during cold periods. If, during the course of the day, they

felt chilly, despite having provided the fuel, they were not allowed to

tend the fire, or indeed warm themselves. If they did so, they were

fined. This draconian rule, reminiscent of Ebeneezer Scrooge and Bob

Cratchit, was later relaxed and employees were allowed

to warm themselves, but only one at a time, and they still weren't

allowed to tend the fire. Near life-size statues stand in niches on the

pavement level of: ‘Rt. Revd. Willaim Talbot DD, Bishop of Oxford, a

founder of the Amicable Society’ and ‘Sir Samuel Bignold Kt., Secretary

Norwich Union Life Office, 1815-1875.’

Notes

There are about 1,500 listed buildings in Norwich:

60 are Listed Grade I,

127 are Listed Grade II*.

There are 31 medieval churches (more than Ipswich, York and Bristol put

together); Norwich is said to have more standing medieval churches than

any city north of the Alps.

Just for comparison, in April 2016 Ipswich had about 711 Listed

buildings:-

11 Listed Grade I,

23 Listed Grade II*,

677 Listed Grade II.

Ipswich has twelve medieval churches in the town centre (13 within the

Borough boundary, including the Church of St Mary & St Botolph in

Whitton).

Home

Please email any comments and contributions by clicking here.

Search Ipswich

Historic Lettering

©2004 Copyright

throughout the Ipswich

Historic Lettering site: Borin Van Loon

No reproduction of text or images without express written permission

2013 images

2013 images