and Halifax shipyard

Spinning off from our page on Halifax Mill and the Ipswich whalers, we needed to include more about Nova Scotia, the actual site of Ipswich's whaling industry at one time. Howard Brown-Greaves got in touch with images and questions about his family connections with Nova Scotia House. Text in double inverted commas are from Howard.

1926

1926"I am researching the site of my great Grandfather’s house which I think was called Nova Scotia House, (though he called it Woodthorpe) and came across your website's Wet Dock map; I would be grateful of any information that would assist in my research, please. Specifically, I am looking for a wider angle shot, preferably an aerial one that positively identifies his house as being there and also identifies it as 'Nova Scotia House'.

I have some wonderful old pictures of the riverside which I am also keen to reach a wider audience, be it on your website or preferably an old book on Ipswich. I have looked at a lot of the Britain from above [see Links under 'Special subject areas/Archaeology') pictures, but none of the images show the house as the images are either too late, by which time the house had been knocked down, or the simply don’t have the detail. Here is the house. My dad is the little boy and the lady on the left is my grandmother (I have bigger versions of this). Taken in 1926. My grandfather was a vicar as St Mary at Elms in Ipswich."

Photos courtesy Howard Brown-Greaves

Photos courtesy Howard Brown-GreavesAbove: "Here is a view from their garden. You can see the chimney of Halifax Mill that is still there on the Wherstead Road [see the aerial photograph on our Whaling station? page; sadly the chimney was recently demolished]. The large building in the foreground is labelled as 'Woodthorpe’s boat house' so this and a couple of other photos I have are what identify the position of the house. It’s all indirect, I don’t actually have a photo that positively identifies the house as being Nova Scotia house."

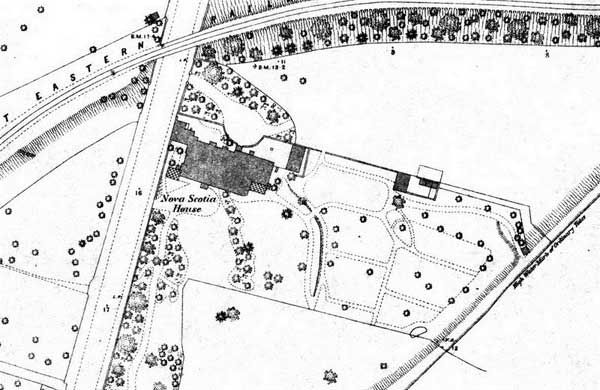

1883

1883We found this detail on an 1883 map of Wherstead Road showing the Great Eastern Railway's Griffin Wharf branch line crossing the road (it's still there today) and the site of the much earlier Nova Scotia House at ninety degrees to the road with its rather attractive gardens running down to the Orwell shore. The legend on this oblique line is: 'High Water Mark of Ordinary Tides'. It is difficult to believe that this green and leafy area is now part of the West Bank container port.

Date unknown (1930s?)

Date unknown (1930s?)"It’s interesting that this seems to indicate that the house was extended after 1883 as the picture of 'The Moorings' [above] shows an additional house."

1949

1949"This photo is from 1949 and by then the area had been re-developed somewhat. The green circle shows where I think the house was."

Nova Scotia House was the home of Captain Richard Hall Gower (1768–1833): see our Street name derivations page. Gower and his family moved there in 1817. He died, aged 65, on his Nova Scotia estate in July 1833. He left a widow, two sons and three daughters whom, because of his abhorrence of public schools, he had been teaching by his own peculiar methods. He lies in a vault on the north side of the church of St Mary-At-Stoke, Ipswich, in the company of master mariners, shipwrights and men of the sea.

Nova Scotia House is clearly shown in the background of Davy's illustration of the laying of the Wet Dock lock foundation stone, 1839.

The Gowers and the time ball that never was

[UPDATE 3.11.2018: Paul Fuller writes – 'Dear Borin, Congratulations on your fabulous website. I'm particularly pleased to see all the photographs of your public clocks, as these are relevant to my research. I am writing a book about time balls and time guns – these were used by mariners to set their chronometers so they could subsequently calculate their longitudes whilst at sea. There is a famous one on the Royal Greenwich Observatory but many ports had these devices in the 19th and early 20th centuries prior to the introduction of the BBC time pips in 1926. Ipswich never had a time ball, but Charles Foote Gower proposed that they should, and he lived at Nova Scotia House right by the docks. Unfortunately he died before anything was decided. I attach some draft text on his life and his father's life. Thank you, Paul Fuller.' Many thanks to Paul for permission to reproduce his draft text.]

"The key player in the call for a time ball in the port of Ipswich was Charles Foote Gower (1828-1867). Gower was a civil engineer and surveyor who was probably uniquely qualified to make such a proposal because his father Richard Hall Gower (1768-1833) had been a noted naval architect and inventor who had been a midshipman with the East India Company who had published several books and articles concerning navigation and signalling.

(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richard_Hall_Gower; See also 'Obituary of R. H. Gower, Esq.', The Ipswich Journal, December 14, 1833, p4, cc 4-5, abridged from 'Memoir: Richard Hall Gower', The Gentleman’s Magazine, vol. ii., p. 469)

His son Charles Foote Gower was elected to the Ipswich town council in 1852. He served as Mayor the following year and took a leading part in many of the town’s institutions, most notably as a Borough magistrate, Vice President of the Working Men’s College and as a Dock Commissioner. He was a warm supporter of the Shipwrecked Seamen’s Society and in his later years took a keen interest in scientific matters, conducting experiments at his father’s beautiful home, Nova Scotia House.

(Paul references this webpage.)

He also lectured to the local Mechanics Institution, where he was a Vice President, and he was well known for his work with the poor.

('Death of Mr. Charles Foote Gower,' The Ipswich Journal, Saturday, February 2, 1867, p5, c1. See also 'Ipswich Mechanics’ Institution', The Suffolk Chronicle, August 3, 1867, p6, c2)

On April 27th 1863 Gower wrote to the Mayor of Ipswich, George C. Edward Bacon, suggesting that a time ball be erected on a pole twenty feet in height positioned on the top of the Town Hall. The ball would be triggered by the 10 am current from Greenwich and unusually the Police would be responsible for hoisting the ball to the top of the pole. Gower’s letter was read out at the town council meeting along with a second letter from Cromwell F. Varley, the electrician to the Electric and International Telegraph Company. Varley stated that the cost of supplying the current from London to Ipswich would be £15 per annum and that the cost of constructing a ball similar to the one in The Strand would be between £120 and £150, depending on the dimensions. Gower had the last word, suggesting a time ball only two feet in diameter would be 'ample for Ipswich'.

Unfortunately the topic was raised at the end of a three hour council meeting and not enough councillors were present to form a quorum.

(Report on a meeting of the Ipswich Town Council under 'Ipswich Corporation', The Suffolk Chronicle; or, Ipswich General Advertiser and County Express, May 2, 1863, p7, c4)

The proposal was eventually rejected because the annual cost was believed to be too high, and Foote unfortunately died in 1867 before his time ball was ever constructed. An illuminated memorial clock was placed on the top of the high tower on the Custom House in his memory.

('The Gower Testimonial', The Ipswich Journal, Saturday, March 2, 1867, p5, c1-2)

This became fully operational in October 1868 but ironically the clock kept local time.

('The ‘Gower’ Memorial Clock', The Ipswich Journal, Saturday, October 17, 1868, p5, c1)

The issue of adopting Greenwich Time was raised in the town council in February 1876 following correspondence with John Plummer of the Orwell Park Observatory to the south east of the town, but the matter was dropped without any clear outcome.

('The Greenwich Time Question', under 'Ipswich Town Council', East Anglian Daily Times, Thursday, February 10, 1876, p3, c3)

Greenwich Time was finally adopted for all public clocks, including the Town Hall, in February 1881. Greenwich Time was received via the 10 am current.

('The Time of Clocks', The Ipswich Journal, Saturday, February 19, 1881, p7, c2).

The British Newspaper Archive."

Note: A time ball or (timeball) is an obsolete time-signalling device. It consists of a large, painted wooden or metal ball that is dropped at a predetermined time, principally to enable navigators aboard ships offshore to verify the setting of their marine chronometers. Accurate timekeeping is essential to the determination of longitude at sea. See also the Time Ball building in Lower Briggate, on our Leeds page.

Nova Scotia shipyard

Nova Scotia: It is unclear exactly when the shipyard that became known as Nova Scotia in the parish of St Mary at Stoke, was first established, although the sale of a shipyard is recorded in the area in 1713. The site, three quarters of a mile downriver from Stoke Bridge, is in the vicinity of today’s West Bank Terminal. The name Nova Scotia was given to the site soon after John Barnard, who already owned a shipyard on the other side of the river in St Clement’s, bought the land in 1749. For a theory as to why this & the neighbouring Halifax yard were so named, see The Villages & Hamlets of the Liberties of Ipswich section, below. By this time Barnard was concentrating most of his activities in Harwich, & used the Nova Scotia yard to store timber & coal & was soon letting it out to others. Barnard’s son William, in partnership with William Dudson, did build several ships here in the early 1760s, the largest being the Speaker, a 702 ton East Indiaman launched in 1763.

After Dudman & the younger Barnard relocated to Deptford on the Thames in 1764, William & John Bayley (exact relationship unknown) hired part of the yard from Barnard Snr. This was the start of the Bayley family’s involvement in Ipswich shipbuilding, which would see them almost monopolise the industry during the nineteenth century. John Barnard was declared bankrupt in 1781 & in the following year the yard was purchased by Timothy Mangles.

William Bayley soon set up his own yard, & it seems he had left Ipswich by 1785. When John Bayley died in March of that year, the business was taken over by his widow Elizabeth. Their four sons all worked in the yard at various times, although it was the second son George, & the youngest Jabez, whose names would become well known as Ipswich shipbuilders.

It was during the period 1787-92 that the short-lived whaling industry thrived in Ipswich, & it was probably during this period that the Bayleys’ moved the main focus of their business to the St Peter’s shipyard. Although Mangles built several ships from Nova Scotia in the late 1780s & early 1790s, such as the Ferdinand in 1791, the yard’s days as a shipbuilding centre were numbered. The Bayley family may have continued to use the yard until the end of the century, but after this time there seems to have been little ship building here.

The whaling industry in Ipswich lasted a mere six years; from 1787 to 1792, based at Nova Scotia shipyard. In the following year, the plant for rendering down the blubber at the Nova Scotia yard on the Orwell (the site of today’s West Bank Terminal) was shut down.

The parish of St Augustine in Over Stoke covered the land south of today’s Felaw Street along the River Orwell down to Belstead Brook. The last reference to the parish was in 1459, and the Priory of St Peter & St Paul then seems to have taken over this parish. With the demise of the priory in 1527 the ecclesiastical authority was attached to the Church of St Peter. The actual land adjacent to the foreshore of the River Orwell to Bourne Bridge seems to have been owned by the medieval leper hospital of St Leonard. This land was purchased by the corporation of Ipswich in 1722. By 1800 there existed a hamlet called Halifax near to Bourne Bridge.

The first known shipyard in the vicinity dates back prior to 1713, as a deed enrolled with Ipswich Corporation in that year records the sale of a yard by one Roger Mather to a shipwright named John Blichenden. This seems to have disappeared by 1749, however, as the notable Ipswich shipbuilder John Barnard (c1705-84) bought the land & built a new shipyard, situated about three quarters of a mile from Stoke Bridge, near to where the West Bank Terminal is now located. He called this shipyard Nova Scotia. About half a mile away, near to Bourne Bridge another shipyard, named Halifax, is first recorded in 1783 and seems to have derived its name from association with Nova Scotia.

Halifax shipyard

Although the sources state that it is not known why these names were given, it seems fairly obvious that they owe their existence to periods of national patriotism, with the two key dates of 1749 and 1783. The French and British were then vying for control of part of North America, which the French called Acadia and the British, Nova Scotia. The British had captured the capital, Port Royal, from the French in 1710, but had not been able to subdue the rest of the colony. In 1749 a concerted effort was made to achieve this, and in June of that year the British governor, Edward Cornwallis, arrived with 13 transports to establish Halifax (named after the Earl of Halifax, not the town) as the new capital of Nova Scotia. By unilaterally establishing Halifax, the British violated earlier treaties and started another war with the French. However, within 18 months the British had taken firm control of Nova Scotia. Later, in May 1783, after the American War of Independence, ships carrying Loyalists from New York anchored at Halifax to begin their resettlement in Canada. By the end of 1783, some 35,000 Loyalists had arrived in Nova Scotia.

The Halifax shipyard was almost next to Bourne Bridge with only a house and garden in between. The first mention of a shipyard dates from 1783, probably established by Stephen Teague, who is recorded as shipbuilding here two years later. Jabez Bayley is recorded at Halifax before 1787, where he built several ships known as East Indiamen. It was at this yard that the East Indiaman Orwell was launched in 1817, the largest craft ever to be launched into the river. Over 100 men were employed in building one large vessel so, with their families, they constituted a sizeable community. This community took its name from the shipyard and Halifax remained a hamlet separate from the rest of Stoke well into the 20th century. This part of Wherstead Road is still referred to as 'Halifax' by some residents today, although it is increasingly known as 'Bourne End' (relating to the nearby Bourne Park). A Halifax House used exist on Wherstead Road, once occupied by Orwells Furniture. The name survives 'officially' in Halifax Road (much of which is a footpath in modern times) that once linked the hamlet to Maidenhall estate, and Halifax Primary School is also located on that estate.

Other Ipswich shipyards

In addition to the two yards in the parish of St Mary-at-Stoke described above, Ipswich had a number of shipyards at various times.

There was a group in the parish of St Clement Church between Duke Street and the east bank of the Orwell, which moved to the vicinity of the Cliff (Cobbold's brewery) when the Wet Dock was built (opened in 1842):-

1. Dock End Yard (bought by R. & W. Paul in 1901 to build their own barges);

2. Colchester's Yard named after William Colchester, sometime business partner of John Cobbold and one of the major barge-builders in the early 19th century;

3. St Clement's Yard,

4. Cobbold Yard close to, and north of, the brewery and owned by John Chevallier Cobbold (1797-1882);

5. Cliff Yard close to, and north of, the brewery;

6. Sometimes a ship was built at John's Ness lower down the river, close to the 20th century Orwell Bridge at Piper's Vale – this can be seen on the labelled river map dated 1805 shown on our Wet Dock map page.

Another group was in the parish of St Peter (today "St Peter's by the Waterfront"):-

7. Mason's Yard west of Stoke Bridge;

8. St Peter's Yard close to the point where Great Whip Street ran down to the water's edge – today this would be on the north of the Island site facing DanceEast; it is shown on the detail form the 1867 map on our Felaw Street page.

Much more about these topics can be found in Moffat, H.: Ships and shipyards of Ipswich 1700-1970 (see Reading list).

Related pages:

The Question Mark

Christie's warehouse

Bridge Street

Burton Son & Sanders / Paul's

College Street

Coprolite Street

Cranfield's Flour Mill

Custom House

Trinity House buoy

Edward Fison Ltd

Ground-level dockside furniture on: 'The island', the northern quays and Ransome's Orwell Works

Ipswich Whaling Station?

Isaac Lord

Neptune Inn clock, garden and interior

Isaac Lord 2

The Island

John Good and Sons

Merchant seamen's memorial

The Mill

New Cut East

Quay nameplates

R&W Paul malting company

Ransomes

Steam Packet Hotel

Stoke Bridge(s)

Waterfront Regeneration Scheme

Wolsey's Gate

A chance to compare Wet Dock 1970s with 2004

Wet Dock maps

Davy's illustration of the laying of the Wet Dock lock foundation stone, 1839

Outside the Wet Dock

Search Ipswich

Historic Lettering

©2004 Copyright throughout the Ipswich Historic Lettering site: Borin Van Loon

No reproduction of text or images without express written permission

©2004 Copyright throughout the Ipswich Historic Lettering site: Borin Van Loon

No reproduction of text or images without express written permission